The Ibos of Nigeria: Members of the Tribe?

WANDERING JEWS: With traditions that echo Jewish ritual, these Nigerians seek official recognition as Jews. ?We want a rabbi to come here and elevate a Torah,? said Harim Chevron Levy (second from right).

Lagos, Nigeria — Efraim Uba was born and raised Catholic in southeastern Nigeria, the homeland of the Ibo ethnic group. He spent 17 years as a Pentecostal preacher before joining a messianic congregation where members wore yarmulkes and tallits but praised Jesus. In 1999, one congregant traveled to Israel and came back claiming that the Ibos were Jews. He convinced the whole congregation to embrace Judaism.

WANDERING JEWS: With traditions that echo Jewish ritual, these Nigerians seek official recognition as Jews. ?We want a rabbi to come here and elevate a Torah,? said Harim Chevron Levy (second from right).

“We believe we are from Israel, and we only recently discovered that so many old Ibo traditions were in fact Jewish ones,” said Uba, 60, who was wearing a large silver Jewish star around his neck. In 1999, he founded the Association of Jewish Faith in Nigeria, an organization with some 20 congregations, most of them in his native region.

He is one of an estimated 30,000 Nigerians — a fraction of the nation’s 135 million people — who claim to be Jewish. In recent years, they have abandoned the Christian faith of most southern Nigerians and are longing for official recognition by rabbis and by Israel. Just this summer, four members of the community were the first to formally convert to Judaism.

Following the examples of Ethiopia’s Falashas, the Lembas of South Africa and Uganda’s Abuyudaya, the Nigerian Jews are part of a growing number of sub-Saharan Africans who have embraced Judaism. Nigeria’s Jews, like the Falashas, claim to be descendants of some of Israel’s lost tribes who settled in what is now southeast Nigeria. By comparison, the Abuyudayas do not claim to have blood ties to the ancient Israelites and converted by following a local leader.

“There is a real phenomenon of construction of a Jewish identity in sub-Saharan Africa over the last few decades,” said Edith Bruder, a French researcher who recently published “The Black Jews of Africa: History, Religion, Identity” (Oxford University Press). “You have a belief among some local communities that they are descendants of Jewish communities who settled there since ancient times. This phenomenon has accelerated recently with the Falasha precedent and the globalization of information.”

The Nigerian Jewish claim was bolstered several years ago with the discovery in the area of an onyx stone reportedly bearing the name “Gad” in ancient Hebrew.

In addition, the Ibo Benei-Yisrael, as they sometimes call themselves, have traditions bearing some resemblance to Judaism. Among them are the circumcisions of newborn males on the eighth day, the separation of women during the menstrual cycles, the mourning period resembling a shiva and the prohibition of eating the meat of an animal that was not blessed. There is also the blowing of a ram’s horn, akin to blowing of the shofar.

But to be officially recognized as Jewish is a tedious process. Israel granted that recognition to the Falashas only after careful vetting. The Abudayadas underwent a conservative conversion six years ago, a path the Ibos are reluctant to embrace. Their reasoning is simple: To convert would undercut their claim to be Jewish by ancestry.

“We are Israelites. This is our identity, and our religion is Judaism, so being denied inclusion into the Jewish family makes us feel lost,” said Michael Ginika, a 53-year-old accounting teacher. “We are trying to come back to Judaism. We were lost for a long time through drifting and scattering, and we are just reaching out to be educated. There is no yeshiva, no rabbi here, so we are in a dungeon.”

Help from abroad to practice Judaism and for recognition as Jews is crucial for these far-flung communities. For the Ibos, it has come in the person of Howard Gorin, the conservative rabbi of the Tikvat Israel Congregation in Rockville, Md. Gorin first became involved in African Jewry in 2002, when he found himself at the helm of the conservative Beit Din — or religious court — that converted some of the Abayudaya Jews from Uganda. A friend then sent him an e-mail from a Nigerian interested in Judaism. Two years later, he landed in Lagos. He has visited Nigeria several times since, handing out prayer material and, more importantly, providing advice about the best way to earn official recognition.

Gorin has been designated chief rabbi of Nigeria, which is both recognition of his dedication and a savvy move to help legitimize the community here and abroad.

Last July, four Ibo Jews traveled to Uganda to attend the installation of that country’s first rabbi.

They used the occasion to undergo a formal conversion before a panel of three conservative rabbis, the first time that Nigerian Jews had taken this step. The conversion process included an interview, a symbolic circumcision and the ritual cleansing.

“I keep telling them that this is a step they need to take if they want to be recognized, and I hope this will trigger a move by others to follow suit,” Gorin told the Forward. The next step, he added, would be to bring Conservative rabbis to Nigeria to perform conversions with the help of Nigerians who could sit on the three-person panel.

The Ibo Jews contend that their 60-million ethnic brethren, who are overwhelmingly Christian, are aware of their Jewish origins but refuse to acknowledge them.

In Nigeria, the Ibos are often identified with Jews because of their business acumen, their attachment to family and education, and the discrimination to which they have been subjected, most tragically during the Biafran civil war of the late 1960s. During that war, they received Israeli military aid, fueling speculation of secret ties between the Ibos and the Hebrews.

The path of those Ibos who have chosen to espouse Judaism has invariably involved a passage through one of numerous messianic congregations that have sprouted in southern Nigeria over the past two decades. Some of those churches mix Christian and Jewish rituals, and so a few of their attendees have decided to explore Judaism exclusively, in most cases after some interaction with Israelis or other Jews.

For instance, there’s Anderson Olidike. He was born an Anglican in the southeastern state of Anhambra 32 years ago. A decade ago, he arrived in Lagos and met an Israeli engineer who brought him to a local Jewish congregation, which he began to attend regularly. At that time, he changed his name to Harim Chevron Levy (the middle name is in reference to the Israeli town of Hebron and not the oil giant) and learned how to lead prayers.

With his beard, black suit, black hat and tzitzits, he elicited some puzzled looks when he met this reporter at a hotel in Lagos and recited some prayers in Hebrew to demonstrate his fluency.

“When people see me with those clothes, they think I am part of a secret organization and they change sidewalks,” he said, smiling.

The following Saturday morning, he led the services, as usual, for the Shuva Letzion congregation. Ten men wearing tallits and reciting familiar prayers gathered in the living room of a house on a quiet street — a luxury in this bustling town. From behind a wooden panel, five women could be heard praying along. They prayed fervently and asked me to recite the prayer for the wine before passing around a glass of Manishewitz.

Levy explained that the community was encountering a series of material obstacles to live a full Jewish life. “We eat kosher, but we don’t have a kosher slaughterhouse,” he said. “We don’t have a mikveh. There are no recognized authorities to officiate for weddings and bar mitzvoth. We need to share tefilin because we don’t have enough of them. What we want is a rabbi to come here and elevate a Torah.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Culture Did this Jewish literary titan have the right idea about Harry Potter and J.K. Rowling after all?

- 3

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history.

- 4

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

In Case You Missed It

-

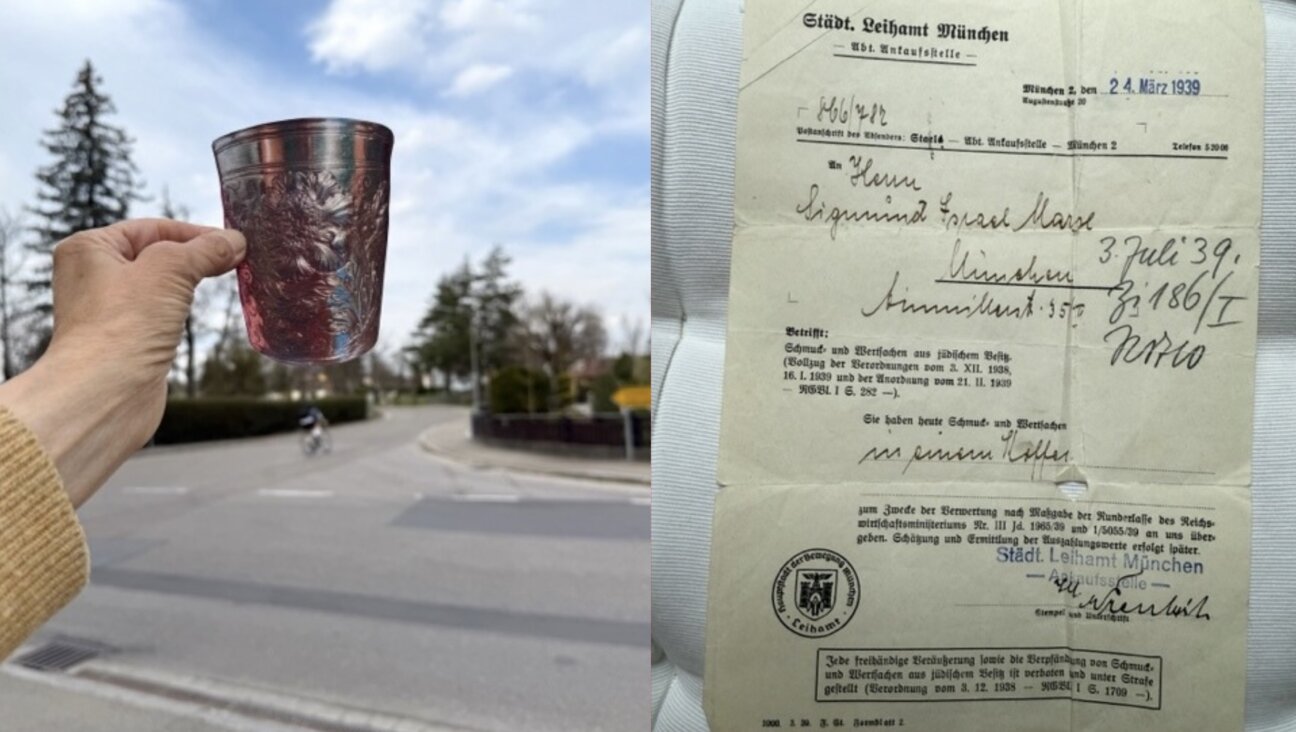

Culture In Germany, a Jewish family is reunited with a treasured family object — but also a sense of exile

-

Opinion Trump’s heedless approach to an Iran deal could be a big problem for Israel

-

Fast Forward In NYC, Itamar Ben-Gvir says he’s changed — and wants ‘the Trump plan’ in Gaza

-

Opinion Itamar Ben-Gvir’s visit to a Jewish society at Yale exposed deep rifts between US Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.