Leaping Brazilian Leopards

Image by Kurt Hoffman

Kafka’s Leopards

By Moacyr Scliar.

Translated from the Portuguese by Thomas O. Beebee

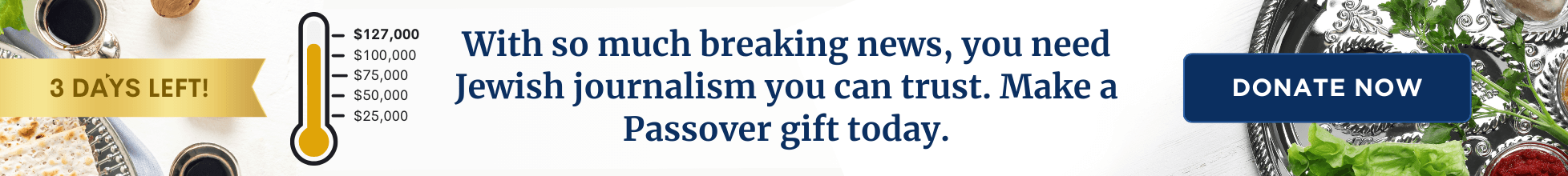

Texas Tech, 96 pages, $26.95

An inveterate dreamer, Moacyr Scliar, the Brazilian-Jewish fabulist who died earlier this year, left behind a veritable treasure trove of enchanting literary artifacts. He was a friend of mine for decades, during which time he published altogether some 60 titles, from novels to manuals of humor, children’s stories, cookbooks and studies on melancholia. Additionally, dispersed in periodicals, are hundreds of insightful interviews and his “Scliarlia”: minor-genre experiments such as diatribes and maxims. As this material slowly makes its way to English-language readers through translations, readers are likely to witness the repositioning of one of the most versatile Jewish authors of the 20th century, from the periphery of culture (Brazil, Scliar would often tell me, is “perennially trapped in the outskirts of things”) to the place where he belongs: center stage.

Franz Kafka Image by Kurt Hoffman

The delightful novella under review showcases Scliar’s talent at its peak. Originally published in 2000, it abounds in his favorite themes: human existence as a sequence of absurd, serendipitous events; bureaucrats’ total ignorance of the value of an aesthetic life; and laughter as a basic prerequisite for facing the apocalypse. Divided into what feel like symmetrical halves, the novel follows its protagonist, Benjamin Kantarovitch, aka Mousy, whose desire to follow orders from Leon Trotsky leads him to another doomed messiah, Franz Kafka. It pivots around a central parable written by Kafka that in Scliar’s hands becomes an excuse to investigate the labyrinthine paths of Jewish history, from the Russian revolution to the Jewish emigrations to the Americas.

Kafka left a hoard of enigmatic parables whose interpretation remains far from exhausted. Thomas O. Beebee, the translator of “Kafka’s Leopards,” calls them aphorisms, which they are, although it is more useful to think of them as Hasidic parables à la Reb Nachman of Bratzlav. One concerns Sancho Panza’s claim to have created Don Quixote. The other is the parable invoked in the title:

Leopards break into the temple and drink up the offering in the chalices; this happens again and again; finally, one can predict their action in advance and it becomes part of the ceremony.

At one point in the first half of the narrative, which is set in Europe, Kafka mistakenly gives Mousy this parable. No hermeneutist, Mousy is incapable of finding mystical meaning in it. Instead, he reads in it an ideological message that, in his view, calls for worldwide revolution. And he acts on that understanding to hilarious effect.

Scliar loved to toy with the idea of multiple layers of understanding and misunderstanding in a single text, and in this novella the mix-up carries tragicomic consequences. In the second half, set in Brazil as the 1964 military coup is unfolding, Kafka’s parable becomes a secret code in the possession of Mousy’s nephew. Again, the cryptic meaning of the leopards in the temple is the cause of a series of unforeseen actions.

Scliar could create characters with few words. His relationship with the reader is that of a partner: He prefers to tell rather than to show, and if he needs to show a scene, he is succinct, deliberate in his descriptions, uncomplicated. Allergic to the kind of writing that places pathos above ethos, and scrupulously avoiding the encyclopedic, Scliar’s oeuvre is occasionally described as Latin American lite. Yet therein lies his resounding achievement: finding humor (not clownish but ingenious) in confusion. “Kafka’s Leopards” simultaneously pays homage to Kafka and is a refutation of Kafka’s esoteric universe, emphasizing its complications while suggesting that life itself should not be obtuse. Scliar looks at the world by stressing its simplicity.

He and I exchanged books every year. His would arrive carefully wrapped, accompanied by a letter mapping for me his intellectual forays in the past few months. My Scliar library is substantial. (“Prolific” is how we were introduced to audiences in public lectures.) Among the jewels he mailed to me is the adventure (not unlike the one imagined by Mario Vargas Llosa in “The Storyteller”) about a doctor who renounces his cosmopolitan life and career to live with an indigenous tribe in the jungle. He also wrote a charming historical novel that makes good on Harold Bloom’s fanciful idea that a woman wrote the Bible. I hope English-language readers are treated to these endearing volumes soon. On the surface, they are quick reads. In truth, their effect lingers just as the taste of fine wine does. They are the byproduct of a true literary original.

Ilan Stavans, a Forward contributing editor, is the Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. His autobiographical meditation, “Return to Centro Histórico: A Mexican Jew Looks for His Roots,” will be published by Rutgers in March 2012.

On Sunday, October 2, at 2 pm, Stavans will pay tribute to Moacyr Scliar through readings and reminiscences at the National Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Mass.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Who killed Jesus? It wasn’t the Jews, writes a scholar of Roman law.

-

Fast Forward Is ‘New Absolute Bagel’ real? A sign stirs fretful optimism on the Upper West Side.

-

Opinion Yes, the attack on Gov. Shapiro was antisemitic. Here’s what the left should learn from it

-

News ‘Whose seat is now empty’: Remembering Hersh Goldberg-Polin at his family’s Passover retreat

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.