American Food Policy Harms Neediest

Image by getty images

Manmade Woes: The famine sweeping the Horn of Africa is exacerbated by misguided policies by donors, especially the United States. Image by getty images

Food plays a central and sensory role in our lives and serves as a map of our history. Meals, recipes and the acts of eating and drinking teach us about who we are, where we live and where we come from.

But at a time of the year when apples and squash flood our tables and nourish our bodies, we’re reminded that millions of people around the world, from Haiti to Kenya, have no nourishment at all.

And it’s not always because of food scarcity. Sometimes it’s because of the unintended but tragic consequences of our own government’s policies — policies that we have the power to change. For example, the U.S. Farm Bill, a piece of legislation that will set the direction of our global food policies for the next five years, is up for revision in 2012. The existing version of the farm bill has had devastating consequences on people in the developing world, filled with provisions that has made it harder to ensure food security for the less fortunate.

The United States is the world’s largest donor of food aid. At first blush, this might make us feel proud. After all, America provides goods to people suffering from famine, natural disaster and conflict. And there is no question that this immediate food aid is critical and saves lives. But the truth is, the way food aid is carried out today — due to laws enshrined in past farm bills — is making our help in a world of ongoing global food crises almost irrelevant.

So, what’s the problem?

First, food aid is expensive and wasteful. Shipping food to countries in crisis from the United States can cost upward of 25% more than purchasing food locally. We’re spending more money and providing less food for those who need it. Shockingly, most of the money we spend doesn’t even go to food purchase. Sixty-five percent of our food aid budget is consumed by shipping costs!

Second, it’s slow. As you would imagine, food shipped to Africa or Asia from the United States can take two to three months longer to arrive than food purchased regionally. This delay may be a matter of life or death. A 2008 Bloomberg article reported that a bag of dried peas from the United States took more than six months to reach a grandfather in Ethiopia. His grandchildren starved to death before the shipment of food arrived.

Had our government not sent the peas on a 12,000-mile journey by rail, ship and truck but instead donated money to purchase food directly from Ethiopian farmers, or provided cash vouchers for the grandfather himself to buy food that is often available but out of financial reach during times of crisis, the children might still be alive.

Third, and most important, if we wish to ensure vulnerable populations’ long-term food security, our current system is not the solution, as it creates a vicious cycle of dependency. And it is far too hampered by our own domestic considerations to be effective. For example, by law, 75% of our country’s food donations must be transported by American companies — a misguided practice that can actually hurt the people we are trying to help.

Consider Haiti: In the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, America’s government provided $173 million in food assistance to Haiti, mostly a lot of rice. In the short term, this rice helped feed thousands of earthquake survivors who had lost everything. But it had an unintended — and devastating — consequence for local farmers. The influx of free rice from abroad brought down the price of Haitian rice so low that Haitian rice farmers couldn’t compete. Because they couldn’t earn an income from their crops, they couldn’t purchase seeds for this year’s crop. As one Haitian farmer put it: “We were already in a black misery after the earthquake. But the rice they’re dumping on us, it’s competing with ours, and soon we’re going to fall in a deep hole. When they don’t give [rice] to us anymore, are we all going to die?”

A much more sustainable approach that American Jewish World Service takes is to support Haitian groups that are rebuilding local food systems and to work directly with rice farmers who are struggling to regain their livelihoods.

Our local partners are doing everything they can. But are we?

We are inviting every member of our community to sign the Jewish Petition for a Just Farm Bill — a collaborative effort among several Jewish organizations — in order to send a message to Congress about our vision and values for America’s agriculture and food policy. A better food aid system will save more lives.

For this campaign, as with all our work, we draw from the richness of Jewish tradition. Two rabbis from the talmudic era offer us insight into today’s global food crisis. Rabbi Natan bar Abba wrote, “The world is dark for anyone who depends on the tables of others.” In contrast, Rabbi Achai Ben Josiah wrote, “When one eats of his own, his mind is at ease.”

These words tell a true and powerful story. It’s up to us to ensure that people around the world can feast from their own harvests and put food on their own tables, for this year and for years to come.

Ruth Messinger is president of American Jewish World Service.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

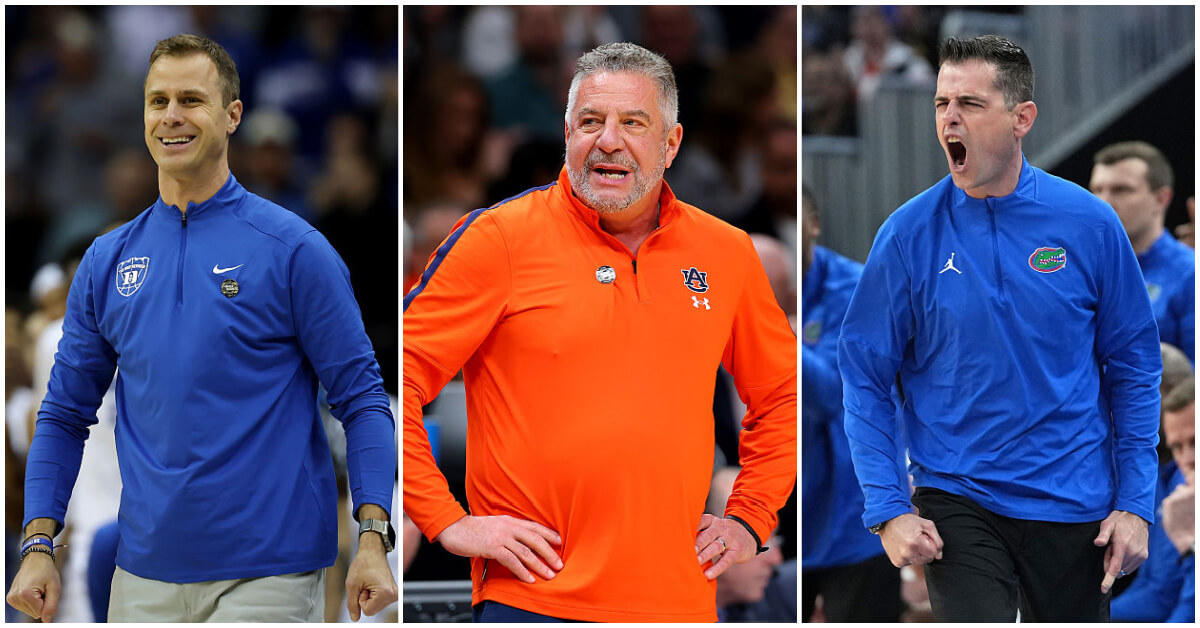

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 3

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 4

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Jerusalem Post editor Zvika Klein, arrested in ‘Qatar-gate,’ says he’s being unfairly prosecuted for his reporting

-

Fast Forward Trump fires national security officials, reportedly at urging of Laura Loomer, far-right Jewish ‘Islamophobe’

-

Fast Forward Display honoring Jewish women graduates of naval academy removed ahead of Hegseth visit

-

Yiddish טשיקאַוועסן: מיידעלע געפֿינט 3,800־יאָריקע קמיע לעבן בית־שמש, ישׂראלTIDBITS: Little girl finds 3,800-year old amulet near Beit Shemesh, Israel

אַן עקספּערט פֿון פֿאַרצײַטיקע קמיעות האָט באַשטעטיקט אַז די קמיע איז געלעגן אויפֿן אָרט פֿונעם אַמאָליקן לאַנד כּנען.

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.