A Case of Uncertain Murder

Rabbi Michael Lotker of Camarillo, Calif., writes:

“Some years ago I heard a Christian minister say that the King James translation of the fifth of the Ten Commandments, the Hebrew lo tirtsaḥ, as ‘Thou shalt not kill’ rather than ‘Thou shalt not murder’ was an accurate translation for its day. His claim was that when the King James Version was published, the English word ‘kill’ meant what we now mean by ‘murder,’ whereas the English word ‘slay’ meant what we now mean by ‘kill.’ Is this true?”

Having once written a column on the linguistic aspects of the Fifth Commandment, I’ll try not to repeat myself. Nor do I have to, the argument cited by Rabbi Lotker being new to me. Does it hold water? Not entirely. It did, however, make me rethink the entire question of “Thou shalt not kill” vs. “Thou shalt not murder.”

The conventional wisdom on the Jewish side has been that Christian translators preferred “Thou shalt not kill” for religious reasons: namely, that as representatives of the religion of “turn the other cheek,” they were uncomfortable with the distinction made by the Hebrew Bible between murder, which is the forbidden taking of human life, and killing, the sometimes permissible taking of human life in self-defense. In the past, I, too, assumed this to be the case. A bit of research undertaken because of Rabbi Lotker’s letter, though, has caused me to change my mind. If the King James Version renders the Hebrew verb *ratsaḥ *in the Ten Commandments as “kill” rather than “murder,” this now seems to me more a result of Hebrew ambiguity than of Christian ideology.

One commonly hears it said that the Hebrew verb for “kill” is harag *and that had God wished to say “Thou shalt not kill” rather than “Thou shalt not murder” in the Bible, He would have said *lo taharog *and not *lo tirtsaḥ. *And yet this is more a back-projection of these words’ meaning in later Hebrew than a correct analysis of what they meant in biblical times. What, according to the Bible, is the human race’s first murder? We all know the answer: It’s Cain’s of Abel. And what is the Hebrew for it? *Vayakam Kayin al Hevel aḥiv vayahargehu *— “And Cain rose up against his brother Abel and murdered [killed?] him,” using *harag *and not *ratsaḥ. *And conversely, when the book of Numbers tells us that a man who accidentally kills another man is entitled to seek safety in a city of refuge, it calls him a *rotseaḥ b’shgagah, *using the verb *ratsaḥ and not *harag. *The biblical distinction, if there is any, between *harag *and *ratsaḥ *is far from clear-cut and is certainly not the same as our modern distinction between “kill” and “murder.”

This is why, I now believe, the King James never uses “murder,” a verb stemming from an ancient Indo-European root signifying death and dying (as in Latin mors, *which gives us English “mortal”), for either *ratsaḥ or *harag. *After all, how could the book of Numbers have called an accidental *rotseaḥ *fleeing to a city of refuge a “murderer”?

Instead, as Rabbi Lotker’s minister observed, the King James uses the verbs “kill” and “slay” — the former almost always for ratsaḥ *and the latter almost always for *harag. *Yet, as is the case with *ratsaḥ *and *harag, *there was no clear distinction between “kill” and the now archaic “slay” in the spoken English of the early 17th century, when the King James translation was undertaken. In fact, the two words have very similar histories. “Kill” comes from Old English *cullen *or *killen, *which originally had the meaning of “to hit” or “to strike.” (As late as the year 1400, we find a Middle English text, “The Destruction of Troy,” *putting into the mouth of a Trojan the words, “The Greeks kyld all our kynnesmen unto colde death,” which indicates that it was still considered possible to “kyl” without causing death.) “Slay” comes from Old English *slean, *which also means “to deliver a blow.” Indeed, its German cognate of *schlagen *still has the latter meaning, so that “to kill” in German is *totschlagen, *“to strike dead” — an exact parallel of “to kyl unto death.” And although by the time of the King James, “slay,” like “kill,” necessarily referred to the taking of life, it still sometimes retained its older meaning into the 15th century.

This is not to say that “kill” and “slay” in the age of the King James were entirely synonymous. “Slay” may have suggested a slightly greater degree of violence and/or intention. (A 17th-century Englishman would have said that someone was “killed” by falling off a horse, but probably not that that person was “slain.”) About this, our minister is wrong. But he is right, I think, in maintaining that the King James Version was not trying to push a Christian interpretation against a Jewish one. Rather, it was seeking to find consistent equivalents for two Hebrew words between which the difference was fuzzy, and it succeeded by coming up with two English words of which the same could be said.

*Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]. *

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 3

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 4

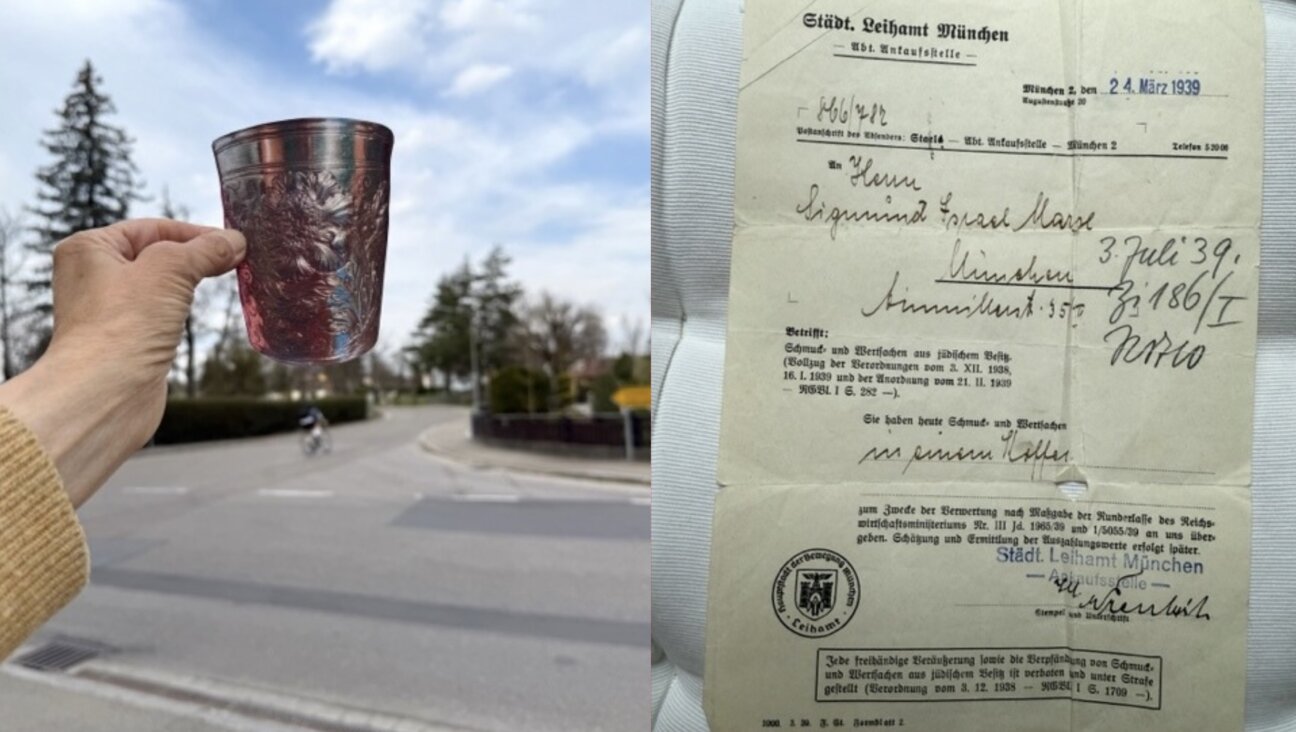

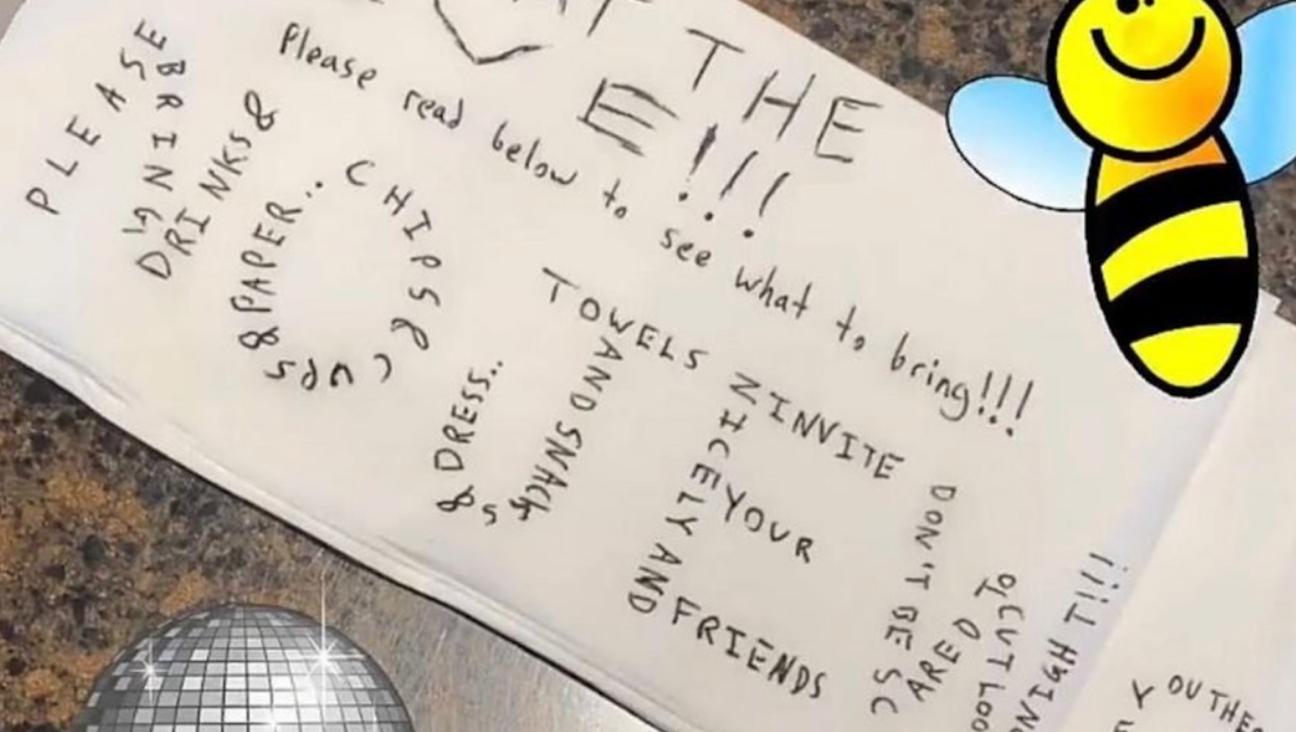

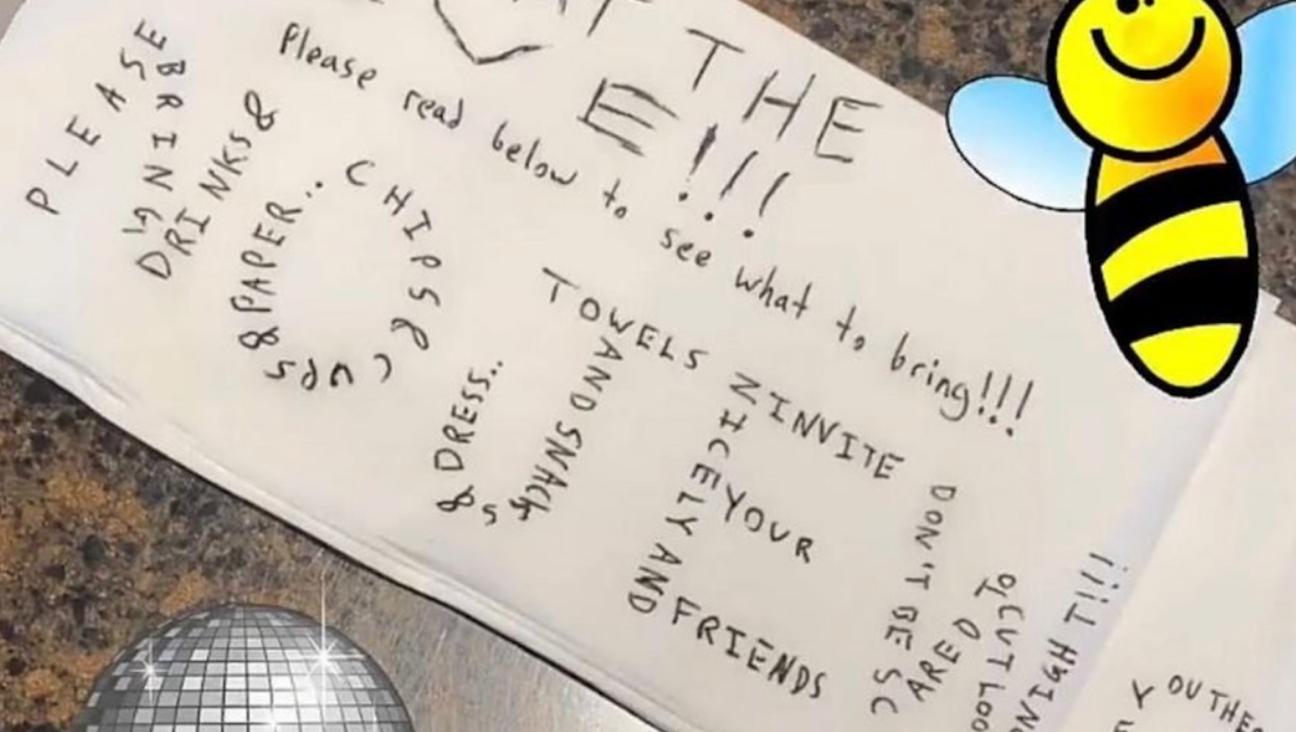

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture In a Haredi Jerusalem neighborhood, doctors’ visits are free, but the wait may cost you

-

Fast Forward Chicago mayor donned keffiyeh for Arab Heritage Month event, sparking outcry from Jewish groups

-

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

-

Fast Forward Latvia again closes case against ‘Butcher of Riga,’ tied to mass murder of Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.