Hidden Treasures of Cairo Genizah

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Sign up for Forwarding the News, our essential morning briefing with trusted, nonpartisan news and analysis, curated by senior writer Benyamin Cohen.

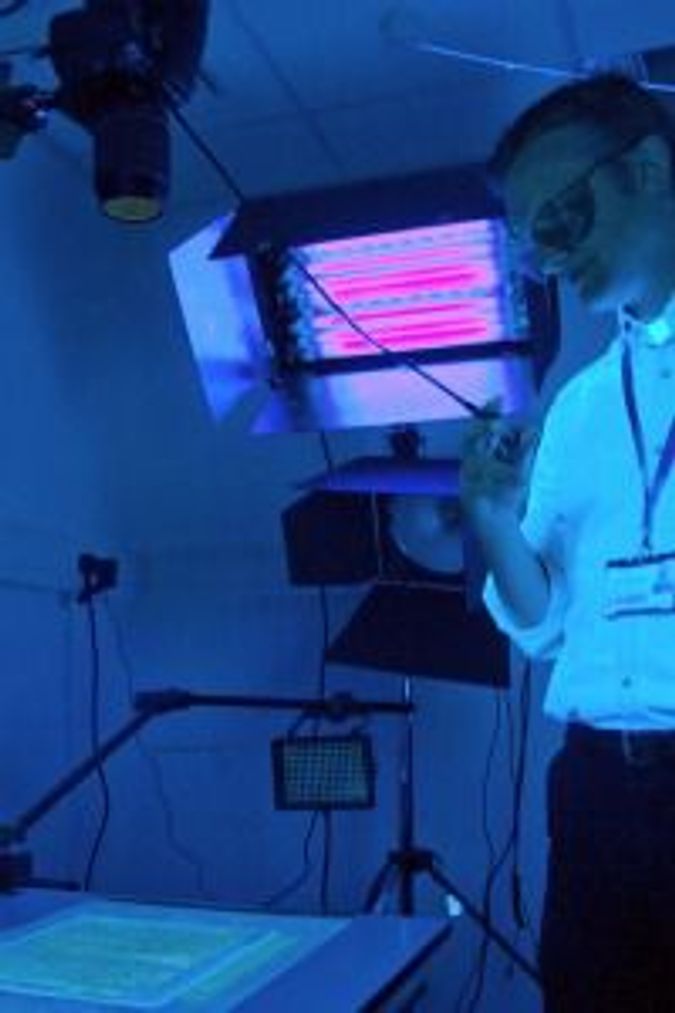

By Hand and Machine: Lucy Cheng works to preserve fragments from the Cairo genizah at Cambridge University in Britain. Image by Cambridge University Library

Computer scientists at Tel Aviv University are using artificial intelligence to gather the fragments of the world’s largest collection of medieval documents, the legendary Cairo Genizah, to tell the story of 1,000 years of Jewish history and culture. They have reconstructed more than 1,000 documents from 350,000 individual items found in the Cairo storage room: more in a few months than in 110 years of conventional scholarship.

They have decades to go before they are finished.

“The Genizah contains information about every single Jewish subject in the world — all learning,” said Rabbi Reuven Rubelow, manager of the Friedberg Genizah Project, which funds the research. “If it is holy, they kept it in this room.”

In some ways, the contents of the Cairo Genizah are more important than the Dead Sea Scrolls, several scholars believe. While the Dead Sea scrolls were the religious literature of a small sect that lived in the desert for a few years, the Cairo Genizah told the story of the day-to-day details of a millennium of Jewish life, from the mundane to the magnificent.

Ultraviolet and Ancient: Scientist Ben Outhwaite uses ultraviolet camera to take images of fragments from genizah. Image by cambridge university library

“What we have learned about Jewish culture and history… in the Muslim world in a century of research is unparalleled,” said Mark Cohen, professor of Near Eastern studies at Princeton University. It is especially true of the day-to-day life of the Jews.

“It’s like looking through a trash can outside your home,” said Phillip Lieberman, assistant professor of Jewish studies and law at Vanderbilt University. “I can tell a great deal about your life from what I find.”

What the Tel Aviv researchers are doing will revolutionize that search. While some of the archive includes complete letters, manuscripts and documents, much of it consists of fragments, some containing only a few words, or pages out of context. The fragments are spread out through 70 different libraries and museums around the world. One page of a letter could be in Oslo and another in Philadelphia.

Nachum Dershowitz and Lior Wolf of TAU’s Blavatnik School of Computer Science are taking the digitized documents and feeding them into computers to rejoin the parts.

Until now, researchers had to rely on serendipity to put together fragments; they would look at a document and remember that it looked like something they saw someplace else, Cohen said. But now, computers are able to learn from their own experience which fragments fit with which. The more documents the computer sees, the better the algorithm will get, an attribute that A.I. scientists call computer learning. The project uses A.I. techniques that were developed over the past decade for myriad reasons but only recently brought to bear on the Cairo Genizah.

Pieces of History: Fragments of Jewish documents from the Cairo genizah. Image by cambridge university library

Although a genizah has been described as a “holy trash” dump, it is actually a word from the Persian, meaning “hoard” or “hidden treasure.” The practice of storing documents in a genizah derives from the Jewish idea that letters, like people, are alive and sacred. When they wear out, or “die,” they are to be treated with respect, especially if, like the Torah, they contain the words of God. They are eventually either buried or, as in the case of the Cairo Genizah, allowed to decay on their own.

Eventually, genizot became neutral receptacles for any community documents. The one in Cairo is by far the oldest and largest.

The brilliant, eccentric Moldavian-born talmudic scholar Solomon Schechter is credited with the discovery of the Cairo Genizah in 1896. Schechter, who at the time was on the faculty of Cambridge University, was told of the Cairo Genizah by Scottish twin sisters, Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson, who had uncovered the trove during their travels to the Ben Ezra Synagogue.

Shown two documents from it, Schechter immediately understood that the sisters had stumbled on a historic treasure. One manuscript was the original text of “The Wisdom of Ben Sirach” (“Ecclesiasticus”), from the second-century BCE, part of the Christian Apocrypha and the origin of part of the Jewish Amidah prayer. Schechter immediately sailed to Egypt.

Founded in the ninth century, the synagogue is located in the Fustat section of medieval Cairo, once home to a bustling Jewish neighborhood. The genizah itself was in a dark, sealed room just under the roof. The contents were protected in part by Egypt’s dry, warm air and in part by a curse that threatened anyone who removed a document.

Schechter found a letter signed by Maimonides among the documents, as well as a draft of Maimonides’s laws that was hand-corrected by the author. The Cairo Genizah also contained the oldest piece of Jewish sheet music, the oldest rabbinic text ever discovered and, as an illustration in an 11th-century child’s reading primer, the oldest use of the Star of David.

It contains social and commercial documents stretching from the 19th century back to the ninth century. This genizah is, in short, a vast storehouse of information on life in the Middle East and its culture and economy, from sex to glassmaking.

Understandably, much of it is still in poor condition. When it was found, paper had crumbled or been stuck together; parchment was torn; text was missing in the middle of documents. Some pages were covered with a molasses-like goop, of undetermined origin. No one had cataloged any of the pages.

Schechter shipped back most of the trove to Cambridge and took some with him to New York when he became president of the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1902. Other scholars and collectors around the world took the rest.

To piece it together, the first order of business was finding out where it all was. “The Friedberg people went around the world and made a list,” Dershowitz said. Some is in private hands, sold by dealers in the 19th century. Seventy percent is still in Cambridge, another 20% to 25% is at JTS, according to the foundation. The rest is scattered around the world.

Now that they know where everything is, the, entire collection is being digitized. Documents or fragments are photographed either by the libraries or by the foundation, shipped to the Friedberg office in Jerusalem and uploaded onto the computer there. Cambridge alone sends almost 10,000 documents on disk by courier each month, Rubelow said.

The documents are scanned using algorithms, segments of which were developed for facial recognition. The computer ignores content and looks for matching physical attributes. “We look at the shape of letters and the spacing between lines and things like that,” Dershowitz said. “If you have two pages from the same book, then the layout of each page is similar.”

So far, the computing project has found about 5,000 fragments that might be rejoined, mostly from collections in Geneva and New York, but scholars have gone through those and affirmed that only 1,000 of them are actual matches.

“This [computer joining] is especially important for historical fragments,” Cohen said. “They are less well preserved. They have the most tears and holes.”

The most important find? Dershowitz said it was the discovery of more works of Saadia Gaon, a 10th-century philosopher. Everyone thought all his extant work had been found, but more was in the Cairo Genizah, and even more has come to light during the Tel Aviv investigation. Dershowitz’s researchers are now experimenting with dating some of the documents and determining their provenance.

Lieberman said the Cairo Genizah scholarship is surprisingly relevant to modern Jews. The Jews in the Medieval Muslim world were highly assimilated culturally and economically into the greater society as modern Jews are, and lived peacefully with their neighbors for centuries. How they did so could be important to know, he said.

The work is unlikely to be completed in the lifetimes of most of the scholars, Dershowitz admits.

“In ‘The Book of Ethics,’” Dershowitz remarked, “it said, ‘It is not your job to finish.’ It’s our job to start. Let other people finish.”

Joel Shurkin is a writer in Baltimore. Founder of the science writing internship program at Stanford University, he has taught journalism at various schools.