Why the Jews? Debate Erupts Over How to Explain the Mumbai Terror

On December 5, just one week after terrorist atrocities left at least 180 dead in Mumbai, The Jewish Week of New York published a blistering editorial, consecrating the event as one more milestone in antisemitism.

“And so Mumbai joins Kishinev, Hebron, Berlin, Babi Yar, Maalot, Sbarro’s, Sderot (we could easily mention 150 other sites) to the annals of sudden infamy,” the editorial’s opening declared. Titled “Another Day in Infamy,” the piece mourned the six Jews killed in Mumbai’s Chabad outreach center during the attack and invoked the “more than 2,000 Jews killed by Islamic terrorists in the last decade alone.”

The editorial cited the Nazis as the terrorists’ historic model.

Sitting in his home, Larry Yudelson, a veteran journalist and observant Jew, was incensed as he read the piece. In a December 11 posting on his popular blog, Yudeline, Yudelson lambasted it as “an editorial that will live in infamy.”

Quoting its opening, Yudelson wrote: “You wouldn’t know from this paragraph — or the eight that follow — that nearly 200 non-Jews were killed in the coordinated terror attacks, whose primary targets were foreigners in Mumbai. The official paper of the UJA-Federation of Greater New York treats them as unpersons.”

It was, he wrote, “a particularly egregious example of the particularistic Jewish response.”

Barely a month after the bloody Thanksgiving weekend terrorist attack, a sharp-edged debate is emerging among Jews on several continents over the proper way to remember and understand the slaughter of the Chabad house victims.

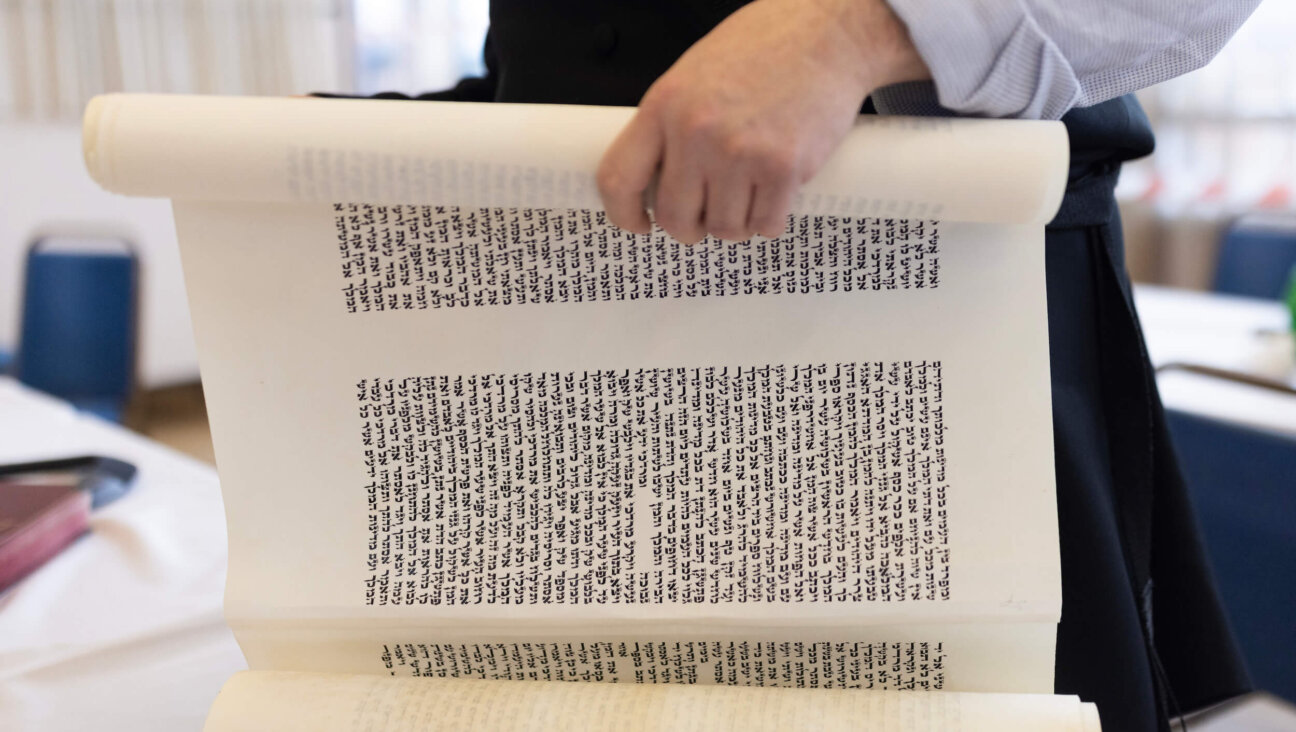

At issue is the legacy of a Hasidic couple and four guests who were held hostage and murdered during a three-day siege at the outreach center sponsored by the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic sect, and primarily used by Israeli Jews and Jews from the West traveling through.

The Chabad center was one of three sites, along with two luxury tourist hotels, captured and held by terrorists during the ordeal. Seven other sites, including restaurants and a train station, were sprayed with hails of bullets, leaving dozens dead, before the attackers settled in for the long siege at the hotels and the Jewish center.

In all, some 180 persons, mostly Indians, were killed; no definitive total had been released at press time.

Since that time, the Chabad house murders have been greeted with outpourings of grief and anger in Jewish communities around the world. The Israeli funeral of the center’s directors, Brooklyn-reared Rabbi Gavriel Holtzberg and his wife Rivka, drew thousands of mourners including Israel’s president, Shimon Peres. Diaspora Jewish organizations issued public condemnations of the attacks in stark terms commonly heard after Israeli terror attacks. Dozens of Chabad centers around the United States have held memorial ceremonies for the victims.

“The jihadist murderers were looking for Jews, and found them,” wrote American Jewish Committee executive director David Harris in one of the bluntest denunciations, published in the July 8 Jerusalem Post. “Of course, Jews were not the only target. But it is telling that in this teeming city of millions, a tiny community, numbering no more than a few thousand, was pinpointed.

“These murderers have been taught in their mosques, madrassas, and media to hate Jews, all Jews,” Harris wrote. “In their demented minds, the very act of being in a Jewish space, any Jewish space, was more than sufficient grounds for being captured, tortured, and murdered.”

In fact, however, it is not clear whether the Chabad victims were hit simply for being Jews or—in a city of 5,000 native Indian Jews whose nine synagogues were left unscathed—they were targeted as symbols of Western Jewry, Zionism and Israel or – as many observers believe – modernity, globalization, Western civilization or some combination of all of them.

Survivors of the hotel attacks report that the terrorists also specifically sought out Americans and British citizens and, of course, the mostly upper-class Indian patrons at these sites. The attackers prioritized them for murder, often passing over other non-Indians. Moreover, while under siege, one of the terrorists at the Chabad center called a popular Indian TV channel. On the air, he ranted specifically against the recent visit of an Israeli general to the Indian-ruled section of Kashmir, where India is locked in a bitter, decades-old conflict with Pakistan. Israel has become an increasingly important arms supplier to India in this clash.

“There were complex dynamics at work here,” said Jerome Chanes, a prominent sociologist of American Jewry and scholar of antisemitism. “It was about India and Pakistan; it was about ethnic tensions, and it was about antisemitism.”

“The terrorists hate the West as the antithesis of their absolutism,” agreed Rabbi Irving Greenberg, a pioneering theologian and scholar of the Holocaust. “And they hate the Jews because they see them as a symbolic representative of Western civilization. The Jews are a focus, but this is a much broader agenda.” By contrast, he said, “the Nazis were focused specifically on killing Jews.”

“What we’re seeing now is not your father’s antisemitism,” said Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum, a professor at American Jewish University in Los Angeles and former research director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “If you don’t see a phenomenon in its entirety, you don’t know how to deal with it.”

A Chabad official, questioned on allegations of Jewish exclusivity, seemed mystified at the charge. In fact, movement spokesman Zalman Shmotkin said, many of the memorial ceremonies that have taken place so far have featured Indian speakers prominently on the platforms and had large South Asian attendance.

Representatives of local Indian-American communities were present and often involved in organizing memorials in St. Louis, San Antonio and Boise, Idaho, among others. The Holtzberg funeral itself, held at Kfar Chabad in Israel, was attended by the Indian ambassador to Israel, said the official.

Still, Judeocentric particularism has its staunch defenders. The author of the Jewish Week editorial, Jonathan Mark, the paper’s associate editor, argued in an interview that “no one would ever challenge the Amsterdam News or El Diario or the Advocate,” referring to leading black, Hispanic and gay community newspapers, “if they took a position that reflects their community.”

“I was writing for the Jewish community,” Mark said. “The events were less than a week old. The Jewish community was uniquely in a position of sitting Shiva. And in a Shiva you don’t walk up to the mourner and say, by the way, 100 other people died yesterday. It’s not to deny the other tragedies, but you’re speaking to a mourner.”

Mark said he felt “heartbroken” at India’s losses — “how could it not break your heart?” — but this particular editorial was directed at a specific point at a particular time. “I don’t think you can be expected to say everything you think or know every time you write.”

Perhaps the most surprising defender of Jewish particularism — given the critics’ fears that it might offend India — was Sumit Ganguly, director of the respected India Studies Program at Indiana University. In an interview conducted mainly in high decibels, he said it was “palpable nonsense” to suggest that Jews were not singled out for attack. “This was rank antisemitism at its worst,” he said. “Let’s not sanitize this. Their only crime was that they were Jews.”

Ganguly acknowledged the political subtleties in the incident that could not be explained simply as antisemitism. Lashkar-e-Taiba, the Kashmir separatist group blamed for the attacks, “has no prior history of antisemitism. Some of their past statements have talked about an Israeli-Indian alliance,” a growing force against a background of counter-terrorism cooperation. Moreover, since Lashkar became affiliated with Al Qaeda in recent years, “there have been remarks that there is a Jewish-Hindu conspiracy against Islam.” Still, he said, “it’s not the kind of squalid antisemitism that exists in much of the Arab world.”

Nevertheless, Rabbi Joshua Hammerman of Temple Beth El in Stamford, Conn., termed it “a grave mistake to focus on the particularly Jewish aspects of this murder when it was an attack, first and foremost, on India, and on western civilization.”

Hammerman, a frequent Jewish Week contributor, wrote on his blog, “We, Jews, have something to offer the world, gained from centuries of experience at being hated for no reason other than that we stand up for life and innocence. Now the world is ready to listen to us — but they can only listen to us if we take our eyes off our own navels and engage them, acknowledging that their suffering is as great as ours.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO