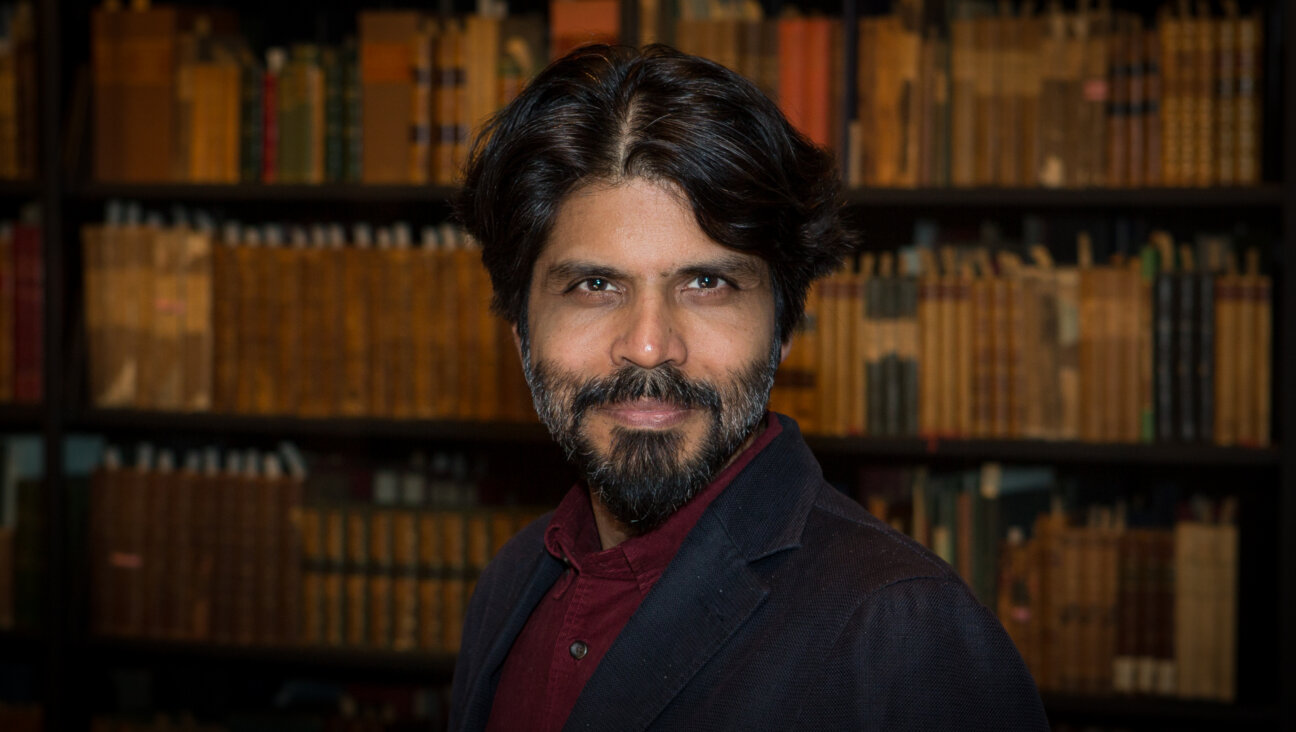

Jason Isaacs Draws a Line in the Sand

A ‘GOOD’ MAN: Jason Isaacs, a star of the new movie ‘Good,’ said he faced antisemitism as a teenager.

As Lucius Malfoy in the Harry Potter films, Jason Isaacs shimmers with pale Aryan-looking evil. As Michael Caffee in the Showtime series “Brotherhood,” Isaacs is a violent and mentally unstable gangster. In Vicente Amorim’s new film, “Good,” opening on December 31 and set in 1930s Germany, you might expect Isaacs to play a Nazi.

A 'GOOD' MAN: Jason Isaacs, a star of the new movie 'Good,' said he faced antisemitism as a teenager.

Instead, he plays Maurice, a secular Jewish psychiatrist. He’s the film’s moral center, despite the fact that — or perhaps because — Maurice is a secular Jew (who doesn’t like Jews) who is also an unapologetic bon vivant. As a self-proclaimed “Jewish man who does almost nothing Jewish in his life,” Issacs said he could relate.

Multiple projects with contrasting roles are what the handsome, fast-talking 45-year-old loves best. To play Maurice, Isaacs commuted to Hungary from “Brotherhood” in Rhode Island. He’d use the plane journey to switch roles, prepping by reading wartime diaries and listening to recordings made upon the liberation of Bergen-Belsen.

Based on the 1981 play by C.P. Taylor, the film centers on John Halder, a professor who becomes involved in the Nazi Party after publishing a novel praising euthanasia. Maurice, a World War I army buddy, helps Halder cope with the mental tic of hearing music when under pressure. When the play opened in New York in 1982, some Jews (my father, for one) walked out (or threatened to) when they witnessed its portrayal of the Nazi as everyman. In The New York Times, Frank Rich praised the debates between Halder and Maurice but concluded that at the play’s sad climax, “we’re still wondering just how Halder ended up there.” John Wrathall’s adaptation clarifies Halder’s journey, which pivots on Maurice’s fate. Halder’s conscience is more intact — and his culpability more overt.

Isaacs recalls telling producer Miriam Segal, when she first approached him about the film, “It’s an offensive notion, the idea that we should apologize for the Nazis.” “She asked me have I read it,” Isaacs said in an interview with the Forward. “I said, ‘Of course!’ I was lying. I read it and apologized…. It’s not only not offensive, but to a Jewish person like myself, steeped in the literature of the Holocaust, it restores the humanity to the entire time period. What I took from it is that as difficult as it is to find where that line is in the sand, there is always a line in the sand.… If you despair and throw your hands up and say, look, I’ve lost my moral compass, let’s just look after the people closest to us — we’re all lost.”

He became a producer on the film, and brought Viggo Mortensen on board as Halder, acknowledging, “I breached Hollywood protocol and had a friend offer him a script.” There is always a line in the sand, but where is it? “I remember just before Margaret Thatcher came to power, there was a party called the National Front,” Isaacs said. They were plain out-and-out fascists, people ‘Sieg Heil-ing’ at their meetings. As a Jewish teenager in the ’70s and ’80s, I was chased and beaten up, and terrified by these people… Margaret Thatcher and the Tory people absorbed the worst fringes, and the National Front went away, or were absorbed. I think a lot of right-minded people in Germany thought by joining that, gradually, the worst fringes would be diluted by the German mainstream.”

Isaacs studied law before attending drama school, and he still loves to debate and research. His Immersion included listening over and over to a BBC Field recording of the British-Jewish army chaplain the Rev. Leslie Hardman, giving a Shabbat service after the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, picking out different weak voices during the singing of “Hatikvah,” reminding himself that each voice belonged to an individual with histories and lives and loves and hates. Listening helped him “get myself out of the way, and try to play a real person.”

Ten months after the film shoot, Isaacs participated in a Holocaust commemoration ceremony. An old man came up to him in his dressing room, and introduced himself as Leslie Hardman. Isaacs told Hardman that it was an honor to meet him. “I’ve never got through this story telling it without —” Isaacs said, his voice trailing off. Hardman told Isaacs about the day of the recording and how he saw people die standing up. For the actor, meeting Hardman, who died in October 2008, brought his own journey full circle.

These days, Isaacs says that he channels his opinionated nature into the actor’s task “to see all points of view.” Isaacs explains that Lucius Malfoy thinks he’s doing good, that eugenicists before the Second World War preached separation of the races, and that’s just what Malfoy’s doing. Malfoy really thinks he’s from better stock. As it turns out, the transition from separatist Malfoy to secular Maurice seems not such a leap after all.

Gwen Orel has a doctorate in theater arts from the University of Pittsburgh. She writes about music, theater and film for various publications.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

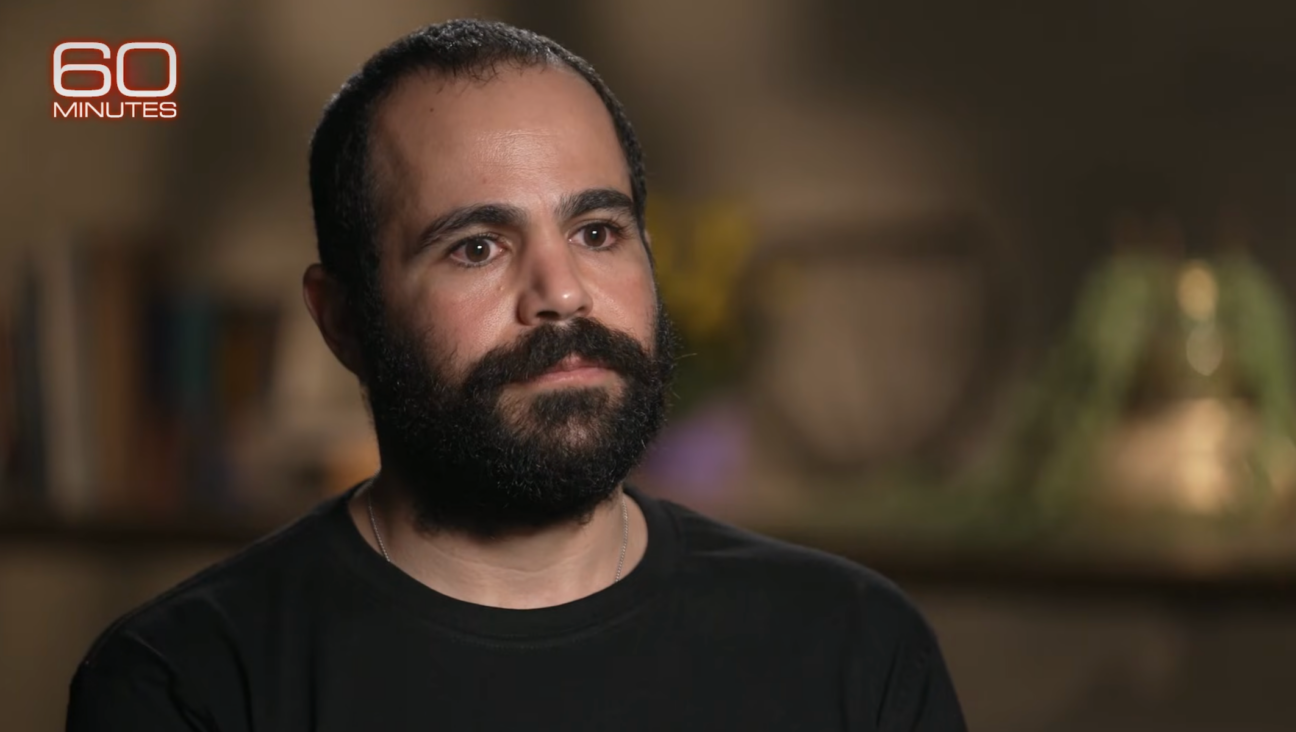

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.