Inner Fire, Outer Ice: The Willful Magic of János Starker

DISSONANCE: Cellist János Starker’s combination of severe control in music and unbridled self-expression offstage has baffled more than one observer.

Legend portrays some Hungarian-Jewish musicians as belligerent extroverts, like the late conductors Georg Solti, nicknamed “the screaming skull” by his Chicago Symphony musicians, and George Szell, dubbed “Doctor Cyclops” by his Cleveland Orchestra ensemble. Yet, the mighty cellist János Starker, born in 1924 to a Hungarian-Jewish family in Budapest, has always looked impassive, in total control, when performing.

DISSONANCE: Cellist János Starker's combination of severe control in music and unbridled self-expression offstage has baffled more than one observer.

Starker’s deadpan face belies the intense emotionality of his music-making, as outlined in a new informal, anecdotal tribute by a former student, Joyce Geeting, “Janos Starker, ‘King of Cellists’: The Making of an Artist” (CMP Publishing, 2008). As this biography asserts, the young Starker was galvanized by his experiences during World War II, when two of his brothers were murdered in Nazi prison camps. Starker himself narrowly escaped this fate by being sent to a labor camp, where he himself was imprisoned. “Janos Starker, ‘King of Cellists’” explains that after his wartime experiences, during his lengthy musical career, Starker has been “unafraid of anyone because he concluded that nothing worse could possibly happen to him. After all that he went through, his resolve was like steel. No one would ever tell him what to do.” In the postwar music world, like a prisoner wary of revealing any inner feelings, Starker was drawn to performers who were stone-faced and relatively immobile, yet hugely expressive both emotionally and musically.

Chief among these was violinist Jascha Heifetz, whom Starker first saw perform in the 1947 Hollywood film “Carnegie Hall” when he was living in Paris after the war, and was “sleepless for a week” while trying to figure out how Heifetz achieved so much while outwardly moving so little. To this day, Starker is the antithesis of the cellists who roll around while playing, waving head and arms in all directions to send semaphore signals to the audience members that they are witnessing an engaged performance. Quoting his friend, pianist György Sebök, Starker frequently tells his students: “Create excitement. Don’t get excited.” Even in an excruciatingly challenging work like Kodály’s “Sonata for Cello Solo.” which Starker mastered at age 15, he is remarkably stoic and still; at least ostensibly.

Among conductors, Starker was similarly drawn to the most physically inert, yet masterful, of all modern maestros, Fritz Reiner (1888–1963), another Hungarian Jew for whom he played in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, and later in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. (Starker launched his solo career in 1958; that same year, he started teaching at Indiana University, where he is still a fixture.) Reiner exasperated some singers with his tiny baton gestures, which some musicians referred to as “making little squares of chocolate,” but he operated — very successfully — under the theory that if musicians were paying attention, they would observe discreet gestures, and if they were not, then flailing around would not help.

Hence Starker’s frank dismissal of the podium “exaggeration” of Leonard Bernstein: “I did not consider [Bernstein] a great conductor,” he states in Geeting’s book, although he does grant him genius status for his polymath efforts as inter alia pianist, composer and educator. Sometimes, Starker’s plain speaking created enemies that lasted him his entire career. After criticizing conductor Eugene Ormandy during a 1950 recording session of “Die Fledermaus” for not knowing the score, Starker had to wait until 1985, the year of Ormandy’s death, before he was invited as a soloist with that maestro’s Philadelphia Orchestra. Although impressed with Yehudi Menuhin’s performances as a boy prodigy, Starker listened with dismay to the middle-aged violinist’s technical struggles to play in tune — Starker’s own ear is razor sharp — and a 1970s concert with Menuhin playing Brahms’s Double Concerto remains “one of the most painful evenings of his life,” Geeting wrote.

There were times when Starker’s frankness simply flabbergasted music lovers, as in his 2004 memoir, “The World of Music According to Starker,” (Indiana University Press), written in exotic, English-as-a-Second-Language prose. Further indiscreet interviews include a 1980 article in People magazine in which Starker admits that some critics feel he is a “cold bastard onstage.” Asked about his rival Mstislav Rostropovich, Starker added bluntly: “What I’d like to see is a little more humility and dignity displayed toward our art, and less self-aggrandizement. Slava is more popular, but I’m the greater cellist.” While by 1980, this estimation may have been substantially true, it would have been more decorous to keep it quiet.

The combination of severe control in music and unbridled self-expression offstage has baffled more than one observer. Starker is reported to be an enthused interview subject at the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction, conveniently located on his university’s campus in Bloomington. An admiring musician reports that not long ago, general amazement was felt at the Yale University Summer School of Music, located in Norfolk, Conn., when Starker departed after a demanding long weekend of rigorous teaching and his living quarters revealed a half-dozen empty bottles of Scotch whisky — to all evidence, personally consumed by the cellist, who nonetheless never looked any the worse for wear.

This combination of wild exuberance and strict discipline helps make Starker a larger-than-life figure. Concerts he cancels are remembered longer than those actually played by most other cellists. In 2007, Nicholas Smith, outgoing conductor of the South Carolina Philharmonic, addressed his audience to reminisce about what local newspapers headlined “the Great Cellist Confrontation.” Around 1990, Starker, hired for $9,000 to play the Elgar Concerto at the new Koger Center for the Arts, rebelled when a building employee forbade him to smoke his ritual pre-concert cigarette, citing the no smoking rules. Starker preferred to walk out on the concert rather than forgo his smoke, and the concerto was performed by the orchestra’s first cellist. More than a fit of pique, this incident illustrates how, in his own mind, Starker, having survived the Holocaust, was not willing to give up what he saw as his right to smoke in a supposedly free society. At age 84, after consuming an impressive quantity of Scotch and cigarettes, Starker is still thriving. Maybe he knows something we don’t?

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

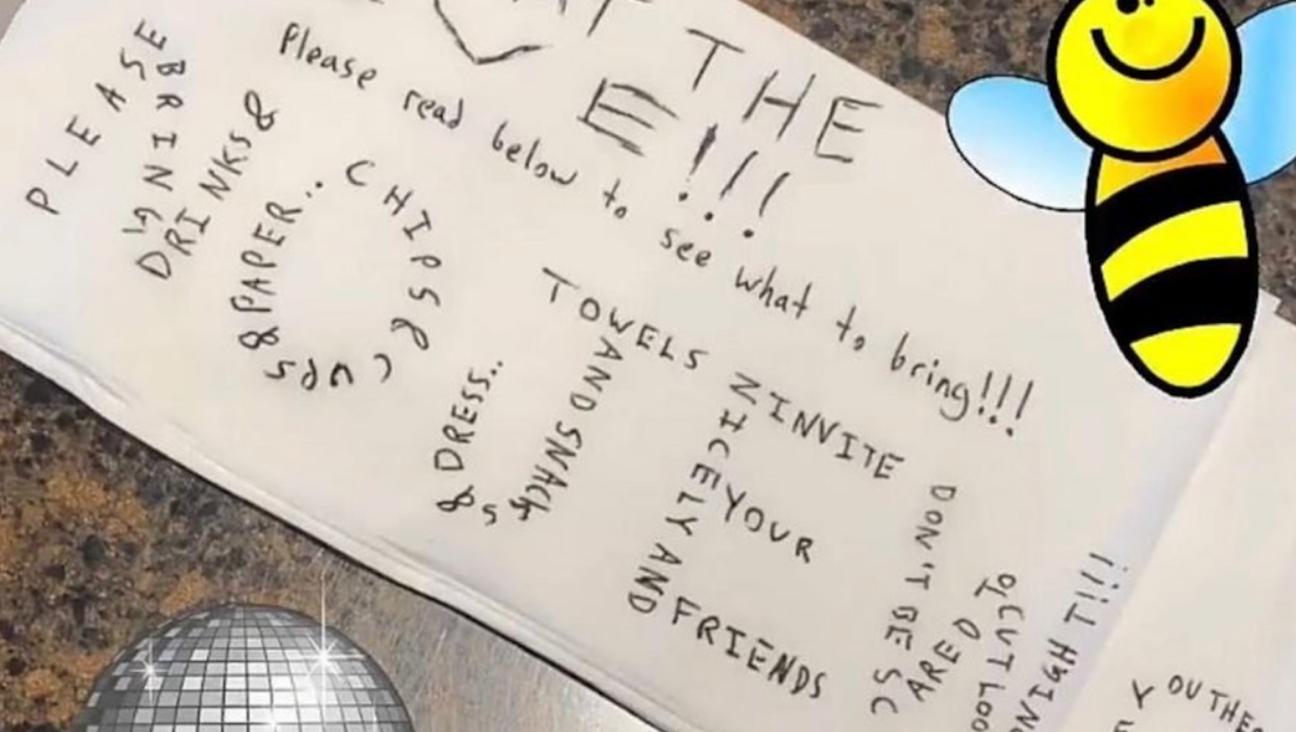

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

- 3

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 4

Fast Forward Columbia staff receive texts asking if they’re Jewish, as government hunts antisemitic harassment on campus

In Case You Missed It

-

News These are the most influential Jews in Trump’s first 100 days

-

Fast Forward Nike apologizes for marathon ad using the Holocaust phrase ‘Never Again’

-

Opinion I wrote the book on Hitler’s first 100 days. Here’s how Trump’s compare

-

Fast Forward Ohio Applebee’s defaced with antisemitic graffiti reading ‘Jews work here’

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.