On the Outside Looking In

Bob Dylan was already rather fond of self-reinvention when, in early 1964, he arrived in Hollywood, metaphorically, via the photography of Barry Feinstein. There, for a moment, and only a moment, he transformed into the poet that people frequently still want him to be. “Hollywood Foto-Rhetoric: The Lost Manuscript” — the recently released book in which Dylan’s words accompany Feinstein’s early 1960s work — is the remarkable document of that moment.

In large regard, “Hollywood Foto-Rhetoric” (Simon & Schuster, 2008) is journalism. Dylan and Feinstein are merely correspondents reporting on the end of the golden era of Hollywood from the perspective of the emerging world in which they are participants. By ’60s standards, their scope is modest. But the book is also art, directly executed and informed by a new worldview with complex roots perfectly exemplified by Dylan himself.

Just two years earlier, Dylan had legally been Robert Zimmerman, a Jewish kid from Minnesota’s Iron Range, proud grandson of Eastern European immigrants. But transformation was in his core. In turn, he’d already become — by imitation, professional and personal — James Dean, Woody Guthrie and, lately, Arthur Rimbaud. When he first arrived in New York in 1960, he told interviewers he’d been in the circus and that he’d traveled with old bluesmen.

Dylan’s ingrained outsider-ness was the direct product of World War II, he has explained. “I was born in 1941,” he told a crowd recently. “That was the year they bombed Pearl Harbor. I’ve been living in a world of darkness ever since.” Like many of his generation, Dylan had a basic distrust of humanity, which was fed by the twin atrocities of concentration camps and atomic bombs. In that way, Bobby Zimmerman transformed into the classic Jewish outsider, Bob Dylan. He could invent new masks whenever he needed, truthful or not. Classic Hollywood, really.

It is a similar outsider-ness — perhaps self-consciously Jewish, perhaps not — that permeates Feinstein’s take on Tinseltown. In one sequence, Feinstein’s camera moves closer and closer to the Hollywood sign, its imperfections magnified as it grows larger. (“Must be some horrendous joke,” Dylan observes.) Feinstein — who shot the album cover of Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’” and was married to Mary Travers of Peter, Paul & Mary — is the perfect tour guide for the 23-year-old Dylan.

In the early ‘60s, Feinstein followed his nose for behind-the-scenes tableaus while working as a production assistant at Columbia Pictures. In 2008, his work is just as remarkable — even without Dylan’s participation. In fact, “Hollywood Foto-Rhetoric” was first scheduled for publication by Macmillan in 1964, only to be pulled from production due to edgy images, such as a sign behind a bar reading “Fagots — Stay Out.”

Public and private, insider and outsider crash in Feinstein’s Hollywood, identity blooming in the space between: Judy Garland (born: Frances Ethel Gumm) on-set but off-camera, the house of Marilyn Monroe (born: Norma Jean Baker) the day she died, mourners at Gary Cooper’s funeral, press agents relaxing poolside. For Dylan, an outsider Jew so defiant that he toured as an evangelical Christian, Hollywood is catnip.

Shades still on, naturally, Dylan riffs in a rarely heard voice. While surrealisms dance with the rhythms of talkin’ blues, the writing is largely free from folk allusions. Absent, too, is the abstraction that plagued “Tarantula” (his 1966 experimental novel) and the scathing put-downs that marked his contemporaneous songs — which isn’t to say that “Hollywood Foto-Rhetoric” isn’t devastating. It’s still pure Dylan.

In “#13,” next to pictures of a beehive-haired woman in an acting class, a “voice of authority” speaks:

all right now, supposin that you’ve just received

a telegram explainin that your husband has

been eaten by a boa constrictor after the atomic

bomb has just fallen in new jersey…now how would

you react in such an instance?like this? Dylan’s writing is frequently classically gorgeous, too: “destroyed ruins/tilt the day,” is a lovely, small phrase that he has written near an image of toppled backlot columns.

In “#16,” Dylan deals with identity directly, ascribing boxes of wigs labeled “Lucille Ball,” “Kim Novak” and “Julie Andrews” with a modernist’s absurdity:

i found me in a box

ripped it open

put myself on

everyone else

did the same.Despite the literal costume-play, it quickly turns to a cautionary tale:

…nakedness

cannot be covered

by a name

an we hardly ever

have t speak

for we dont

call

each other anything. Especially in Hollywood, it seems, Dylan is wary of the notion of fixed identity. In the book’s concluding sequence, “#23,” next to images of film stars clutching their Oscars, the statuettes at center frame, he recalls the Tom Paine Award he’d received from the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee the preceding year. Uncomfortable at being pinned down by the new old left as a protest singer, he’d reacted with a knee jerk, accepting with a boo-inducing speech in which he sympathized with Lee Harvey Oswald. This effectively severed ties with his earliest patrons. Always identifying, that Dylan.

He writes, “the room was silent mama” (a rare concession to blues vernacular), and continues,

the room was silent

except for this hysterical laughin

stemming from the ridiculousness

of such useless property

but i couldnt tell

who was laughing mama

i couldnt tell if it was me

or this thing

i was holding. Dylan’s art — here lashed not only to a specific time, but also to specific images — would rarely be so fixed again. Dylan was always making sure that the audience, at least, would wonder whom it was they heard laughing. No wonder he got out of town quickly.

Jesse Jarnow hosts the Frow Show on WFMU. He lives in Brooklyn and blogs at jessejarnow.com.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

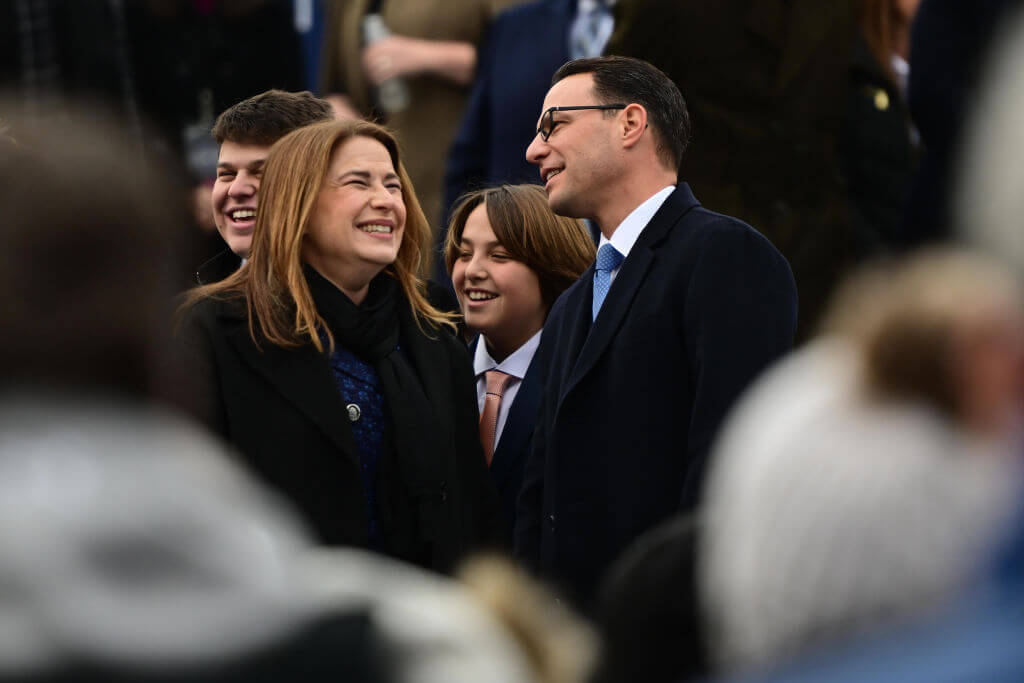

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

- 4

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Jewish students, alumni decry ‘weaponization of antisemitism’ across country

-

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history

-

Opinion Why can Harvard stand up to Trump? Because it didn’t give in to pro-Palestinian student protests

-

Culture How an Israeli dance company shaped a Catholic school boy’s life

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.