Bam! Pow! Whack!

Maxine, at just-turned-4, is in a superhero phase. This despite the fact that the only superhero she’s actually seen is WordGirl (the vocabulary-building crime-fighter from the planet Lexicon) on PBS. Both Max and her big sister, Josie, love the show; for Halloween, they dressed as WordGirl and her chimp sidekick, Captain Huggyface. (Guess who had to be the sidekick.) Jonathan played one of the arch-villains, The Butcher, who butchers the English language and hurls meat at the superheroes while bellowing catchphrases like “Pastrami Attack!” and “Chicken Cordon blam!” His Kryptonite is tofu. I dressed as another supervillain, Lady Redundant Woman, a disgruntled copy shop employee who has an unfortunate industrial workplace accident after which she can make duplicates of herself to do evil. Yes, we are a family of nerds.

Maxine has absorbed superhero culture by osmosis. Often, when we take walks, she wants to enact super-scenarios: “You try to steal the diamond and I’ll stop you!” she orders me. Or “You try to do evil things with cheese and I’ll show up!”

She’s far from the only little Jew with a superhero obsession. As everyone knows, superheroes have an illustrious Jewish history. The creators of Superman, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were geeky Clevelandites who imagined a fellow immigrant, this one from even further away than Eastern Europe, becoming a hero to all Americans. Other comic book champions, like Stan Lee (Stanley Lieber), who begat Spiderman; Jack Kirby (Jacob Kurtzberg), who begat Captain America; Bob Kane (Bob Kahn), who begat Batman; Joe Simon, who begat Captain America, and Gil Kane (Eli Katz), who begat Green Lantern, were Jews. Like their heroes, the creators often created new self-identities via Anglicized names. Nomen est omen.

Many superhero comics have addressed World War II. Many have featured heroes who appeared bookish and awkward, but were secretly powerful, brave and so well-muscled they make Hugh Jackman look like Dakota Fanning. Michael Chabon’s brilliant Pulitzer-prize-winning novel, “The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay” (Picador, 2001) and the Jewish Museum’s Superheroes show from a couple of years ago, which displayed art from the golden age of comic books (1938-1950), dealt explicitly with the contributions of Jews — and their attraction to — superhero stories.

Today, superheroes are explicitly, rather than codedly, addressing their Judaism. Sabra is an Israeli superhuman former Mossad agent who has appeared in The Incredible Hulk, X-Men and Avengers comics. Kitty Pryde, one of the X-Men, wears a Star of David necklace and observed Yahrzeit in the comics. (In the film series, not so much.) Her nemesis Magneto, who first appeared in the 1960s, was described in the ’80s (and the films) as a concentration camp survivor. And in 2002, Max Gross wrote in the Forward about the outing of The Thing, the Golem-like oversized crackled-stone crime-fighter in the Fantastic Four series, as a Jew. The Thing (born Benjamin Jacob Grimm) winds up saying the Shema over a wounded friend, and explaining that he’d kept his Jewishness hidden because he figured “there’s enough trouble in this world without people thinkin’ Jews are all monsters like me.”

(The Thing’s creator, Jack Kirby, who died in 1996, always thought of him as Jewish, and reportedly kept a drawing of The Thing in a kippah and tallit. But it took 40 years — such a biblical number! — and the work of a non-Jewish writer and editor for The Thing’s Jewish origin story to appear. Perhaps these non-Jews, artists who came of age in a more pluralistic time, were more comfortable than Kirby was with making The Thing’s religion public and explicit.)

All superheroes value Tikkun Olam, fixing the world. We may disagree with their methods, but they get results. Superheroes always get the bad guy, without moral ambiguity. Good is unequivocally good, and bad is unequivocally very bad.

And this is their attraction to little kids like Maxine. She’s younger, more powerless, less verbal than her sister. The notion of a secret identity resonates with her as much as it does with immigrant comic book artists. (“I may seem like a mild-mannered child who still wears pull-ups at night…”). For small people who don’t get much control over the universe, who have to answer to parents and bossy big sisters, whose environment is circumscribed, playing superheroes confers strength and power. Cool suits! Bold colors! Superfast! Superstrong! And kids are working on their own impulse control: the emotional, as well as the physical, hugeness of the villains and heroes appeals to them.

I think more boys than girls are superhero fans because boys tend to express aggression more physically (girls are just as mean, but it’s a verbal, social, surgical Tina Fey-like meanness). And as boys get older, those who process information visually or have trouble with reading may continue to enjoy comics. They’re not deviant; they’re a gateway to literacy! I’d also give superhero fans the delightful non-fiction book “Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman” by Marc Tyler Nobleman, illustrated by Ross McDonald (Knopf, 2008), which was just listed as a Notable Book for Older Readers by the Sydney Taylor Book Awards committee of the Association of Jewish Libraries. (Oddly, given the history involved, there’s no mention in it of Siegel and Shuster being Jewish. Still, it’s a great read.)

And as experts have pointed out, comics provide a safe fantasy world in which children can cope with their own feelings of anger and budding sexuality. Parents just need to supplement superhero tales with other kinds of storytelling. (There are brilliant comics and graphic novels that don’t feature superheroes; they’ll be the subject of another column.) “The ‘boobs and boots’ aspect of superhero comics does concern me,” said my friend Julie Holland, an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at New York University. “I always think it’s better to have a normal representation of the female body instead of an enhanced kind that can’t be obtained except through surgery.” She pauses. “I do like the boots, though.”

And so does Maxie.

- Write to Marjorie at [email protected]. *

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

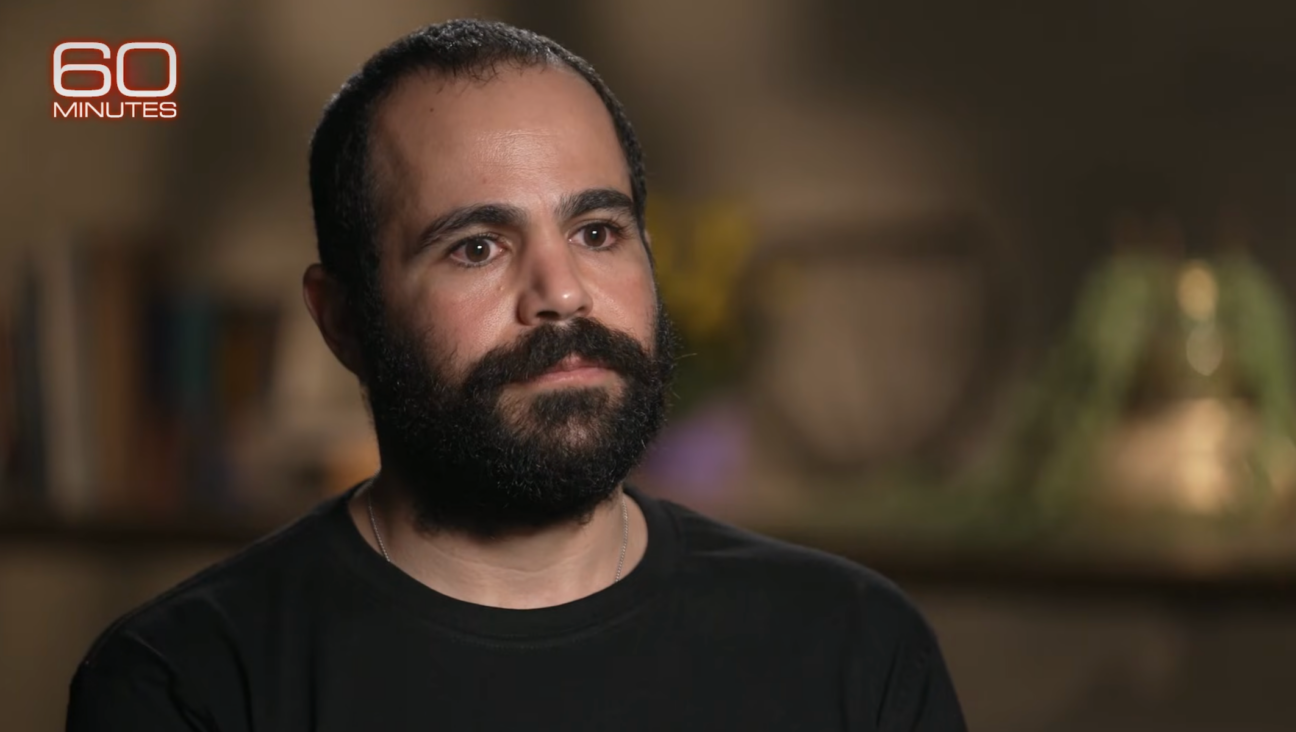

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.