What’s So Jewish About Test Prep?

Image by courtesy of sam sellers

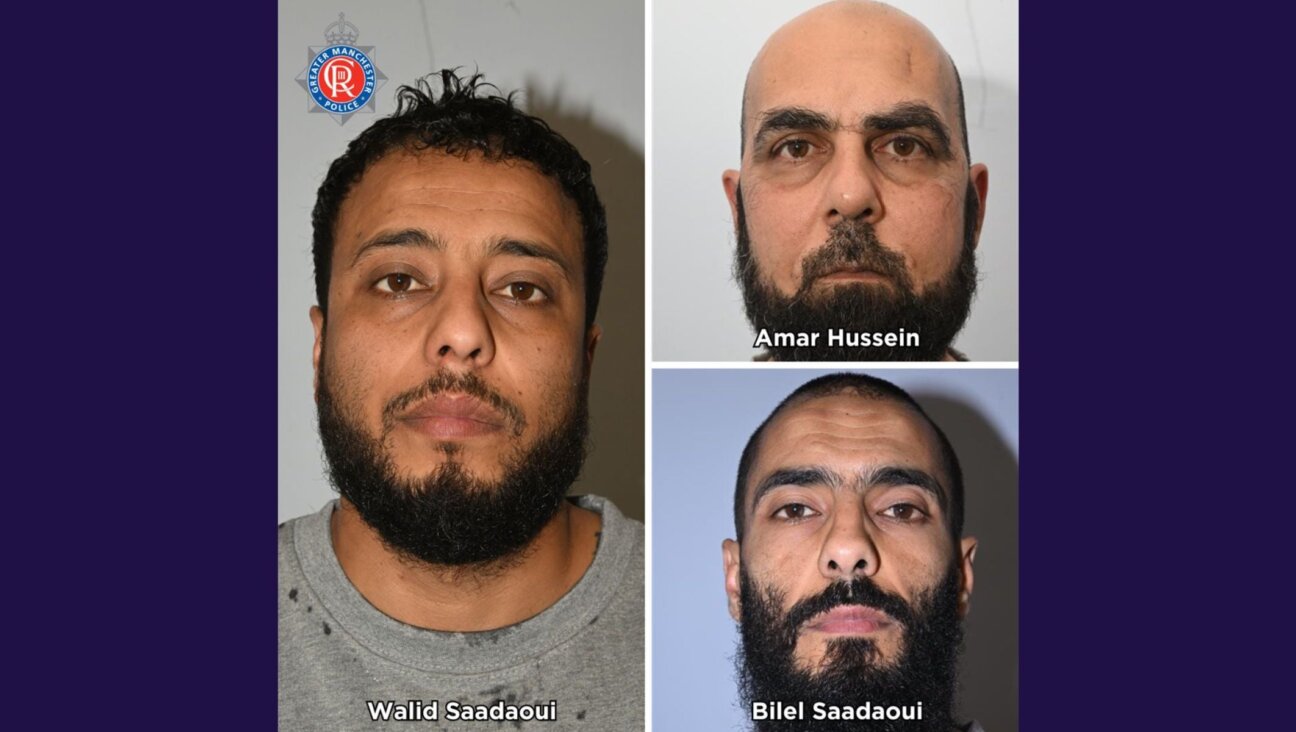

Lyrical Learning: Rabbi Darkside, aka Sam Sellers (far left), co-founded Fresh Prep, which uses rap and street culture to tutor students for the New York State Regents Exams. Image by courtesy of sam sellers

Princeton Review, of course, was not the first test preparation business with a Jewish founder. That would be Kaplan Inc. — named for Stanley Kaplan, the son of immigrants, who started his business in the basement of his parents’ Brooklyn apartment in 1938. Kaplan was ultimately sold to the Washington Post Company for $45 million in 1984.

Princeton Review was also not the last Jewish-founded test prep company. Manhattan GMAT was founded in 2000 by Zeke Vanderhoek, a graduate of the Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School in Rockville, Md., who went on to Yale and Columbia universities. And California-based Revolution Prep was co-founded in 2002 by Jake Neuberg and Ramit Varma, who met at the Anderson School of Business at the University of California, Los Angeles.

But today’s newer companies, still populated with Jewish founders and tutors, are different in that they employ methods ranging from standard tutoring to approaches incorporating music, customized learning and even hypnotism. Though it’s hard to state with certainty how effective any one approach is, it is ironic that many got their start with industry giants Kaplan and Princeton Review.

“[Katzman] refers to us and others as the Princeton Review diaspora,” said Bara Sapir, founder and executive director of Test Prep New York, a boutique, new-age company that takes a holistic approach to test preparation. Sapir, who calls her method “yoga for the mind,” evaluates each student, taking note of their particular learning style, and offers a customized, comprehensive approach that includes a music-infused audio program to teach relaxation, along with such options as hypnosis and neuro-linguistic programming.

Sam Sellers is another tutor tapping into the power of music for test prep. Sellers goes by the rap moniker Rabbi Darkside. He’s a co-conceiver of Fresh Prep, a program run by the Urban Arts Partnership that uses rap and street culture to tutor students for the New York State Regents exams. Students receive a thick workbook and are instructed to download, and memorize, songs from Fresh Prep’s website. Sellers has written 51 of those songs and four albums.

A former public school teacher, Sellers said he’s been called Rabbi Darkside since age 16, when he was just dabbling in freestyle rap. The name has been a self-fulfilling prophesy, even though few of his students are Jewish. “The rebbe side of it is the teacher and means being a lifelong learner. I definitely strive to be that,” he said. “And the dark side is the double life you lead as an educator and entertainer, and the struggle to meld those two things as much as possible.”

The Jewish nature of test prep stems from Judaism’s focus on education, said Katzman, who left Princeton Review in 2008 to start 2Tor, an online degree program in conjunction with several universities. “The nature of the religion is about inquiry, so I think the focus on education is consistent with all the values of Judaism,” he said.

Paul Kanarek, a Jewish member of Princeton Review’s early team, said Princeton Review had many Jewish clients when it started, thanks to word-of-mouth marketing. Even in a slow economy, Kanarek said the test prep business presents tremendous economic opportunity, as parents, especially Jewish ones, are often willing to sacrifice other luxuries for good education. “You can be entrepreneurial, make a difference — the whole tikkun olam thing — and make money,” he said. “It’s a wonderful triad.”

What’s more, he added, Jewish mothers love to tell people their offspring help others get into college. “There’s a lot of naches around this business,” he said. “Don’t underplay that. It’s incredibly powerful, almost reverend-like.”

Drew Valins, a University of Pennsylvania graduate, started Satellite Test Prep in New York City in 2010 as a way to make money while pursuing an acting career. “My mom, being a Jewish mother, was like, ‘Why don’t you try tutoring for the SAT? You’re smart,’” recalled Valins, who draws on a master’s in counseling and his acting skills to help prepare his students to test well under pressure. “A little slogan I say to parents is, I bring a little sanity to a very insane situation,” he said.

But Valins doesn’t use religion or spirituality to connect with clients, unlike Sapir, who instinctively turns to spirituality as a way of connecting with students and helping them let go of anxiety in order to excel on their exams.

Sapir said that her ability to think critically, a component of standardized tests, was shaped by her Jewish experience. “My way of understanding the tests, and looking at it as a metaphor, probably mirrors the way I read Jewish texts,” she said.

When working with Jewish students, Sapir says she does use religious concepts when appropriate. “We can’t use kavanah with someone from Bayside, but we’ll use the word ‘intention,’” she said.

The less subtle Jewish influences in her work include her audio program, which was created by a Jewish musician, Katie Down. (Sapir and Down performed in a Ladino band for a few years.) “It’s definitely not klezmer, but [Down’s] sensibility is world beat, so it does have some of the Sephardic open world music tradition in there,” Sapir said. Though not overtly Jewish, she said, “It’s singing from the soul to help people perform their best.”

E.B. Solomont is a freelance writer living in St. Louis.