Barry Manilow Returns To His Jewish and Broadway Roots With ‘Harmony’

Image by getty images

He Wrote These Songs: Barry Manilow has been singing songs from his musical ?Harmony? during his most recent tour. Image by GETTY IMAGES

At a few minutes before 2 p.m., the mood in the Snapple Theater Center was loose, the ambiance casual bordering on schlumpy. In a low-ceilinged rehearsal room, there was a long table cluttered with papers, three-ring binders and Diet Cokes. A stage manager typed away on a laptop. A box of Cheez-It crackers and a pump dispenser of hand sanitizer stood on what passed for a craft services table. An air conditioner clunk-clunk-clunked away.

In front of an upright piano where assistant music director John O’Neill was building chords and picking out notes, a half-dozen male actors in jeans and sneakers slouched in front of their music stands and horsed around. A carton of coconut water at his feet, Wayne Alan Wilcox — you may remember him as Marty on “Gilmore Girls” or as Gordon in the film version of “Rent”— pretended to hump one of his fellow actors as he sang a song called “Every Single Day.”

“Every single daaaaay,” he crooned while he thrusted. “We’ll remember what we do todaaaaaay. Words we didn’t saaaaaay we’ll remember every single daaaaaay.”

Read Barry Manilow’s 8 Most (Maybe) Jewish Songs

If those lyrics seem familiar, it might be because you’ve heard Barry Manilow sing them on his most recent tour. The song tends to turn up between his cover version of Frankie Valli’s “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” and “Lay Me Down,” from Manilow’s 1975 album “Tryin’ To Get the Feeling.” He also performed it earlier this year at New York’s St. James Theater, as part of his “Manilow on Broadway” show.

Striking a Chord: The cast and creative team at the first rehearsals for ?Harmony? by Barry Manilow and Bruce Sussman. Image by John Maley

That may have been the first time “Every Single Day” was sung on a Broadway stage. But at the rehearsal, the unspoken hope was that the song will wind up there again, perhaps as early as next year, as part of “Harmony,” a musical that has been an obsession of Manilow and one of his longtime writing partners, Bruce Sussman, for the better part of two decades. The musical concerns the Comedian Harmonists, a sextet of male German singers — some Jewish, some not — who rose to fame in the 1920s and ’30s but had their careers crushed by the Nazis. The subject matter seems just about as far from “Mandy” and “I Write the Songs” as one could imagine, but both Manilow and Sussman have said that the project speaks to their Jewish upbringings and to their love of musical theater.

“Harmony” premiered in California in 1997, where it opened to middling reviews; plans to eventually bring it to Broadway were sidetracked by financial troubles and a protracted legal battle with one of the show’s original producers. At one point, Manilow was hospitalized for stress that was attributed to the fight over “Harmony.” Now that Manilow and Sussman once again have the rights to the musical, they will be opening a new version of the show, this time directed by Tony Speciale, former associate artistic director of the Classic Stage Company in September at Atlanta’s Alliance Theatre. Then in 2014, onward to the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles. And after that, well, as Sussman puts it, “Keyn’e hore.”

Sussman was seated at the rehearsal table, but Manilow wasn’t in the room — he was out in the hall, chatting with his publicist and his personal assistant as the actors turned pages in their three-ring binders, stopping when they reached a musical number called “Harmony, Part 3.” The approach seemed to be for the actors to work as much as possible with their director and without the looming presence of a multi-platinum, Grammy, Tony, Emmy-award winning performer making them jumpy.

At precisely 2 p.m., rehearsal started in earnest, and there was a palpable shift in the room. Someone turned off the air conditioner. The postures became straighter. The actors performed their six-part harmonies with a new precision that almost allowed you to imagine that they were wearing tuxedos and standing on a proscenium stage in a concert hall rather than wearing hoodies and caps while standing on a buffed wooden floor littered with Starbucks cups.

“If we’ve got harmony, we’ve got a chance,” they sang.

When they finished with the song, O’Neill looked to the actors. “Shall we let Barry have a listen?” he asked.

There was a long silence. Then, one of them said, “Sure.” But none of the other actors said anything.

“Weee-ell,” O’Neill said, “Let’s try it one more time before we do that.”

At first, the idea of Barry Manilow co-writing an original Broadway musical might seem like a departure for him, but in fact, musical theater was where he got started. Originally the accompanist for an off-Broadway show called

“The Drunkard,” featuring public domain songs from the 19th century, Manilow eventually wrote an entirely new score. “The Drunkard” opened in 1964 and went on to play off-Broadway at the 13th Street Theatre for eight years. And when Manilow (né Barry Alan Pincus) met Bruce Sussman (né Sussman) in late May 1972, the two talked about collaborating on musicals and about their affinity for intelligent, contemporary shows like Stephen Sondheim’s “Company.”

“Before the pop career hit, this is where I wanted to be. I wanted to be in the musical world,” Manilow said.

“When I met Barry, I was a theater writer,” Sussman said. “I didn’t know anything about pop music, and we were going to write shows together. But it was kind of an ugly time in musical theater back then.”

“All the people we knew in New York were turned off by everything that came after the Golden Age on Broadway we grew up with,” Manilow said. “And then ‘Company’ happened, and that’s when everybody I knew said, ‘Let’s get back into the theater.’”

“I remember talking to you about ‘Company’ the first night we met, and you said, ‘I saw it 17 times,’ and I said, ‘I saw it 21 times,’” Sussman said.

“I second-acted it,” Manilow said. “I’d go in for free after intermission.”

“So did I. We were both poor. We stood outside. You can’t do that anymore. They ask for Playbills and ticket stubs now,” Sussman said. “I remember I wrote Sondheim the only fan letter I ever wrote in my life, when I was a senior in college, and he wrote back and invited me to the opening night of ‘Follies’ at the Winter Garden. I sat in the eighth row between Ethel Merman and Danny Kaye, and I thought, if I die right here and now, it will have been a full and rewarding life.”

Manilow and Sussman were sitting on barstools along with Speciale in the Snapple Theater Center’s upstairs lobby, outside the 200-seat house where the long-running murder mystery “Perfect Crime” is performed.

The two men have an easy repartee honed through 41 years of friendship and business dealings. Dressed in a black button-down shirt and matching jeans, Sussman was bearish in an amiable sort of way, an enthusiastic raconteur of Manilow’s tales and his own. Manilow, in belted black slacks, black shirt, gray sport coat and blindingly shiny black shoes, was more measured and reserved in his speech; he seems more than willing to let Sussman play Boswell to his Johnson. Sucking contemplatively on an electronic cigarette, Manilow presents a beatific, off-stage presence, suggestive less of a pop superstar than of the caterpillar in Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.”

“Onstage, I’m the pop singer. It’s a gig; it’s a job,” Manilow said.

“Harmony” is not Manilow and Sussman’s first experience writing the sort of character-based material that “Harmony” requires. The men worked together on the scores for the animated films “The Pebble and the Penguin” and “Thumbelina,” and for the TV and stage versions of “Copacabana,” based on the monster hit song written by Manilow, Sussman and Jack Feldman. The song is sort of a three-verse musical in itself. And, over the past 40 years, Manilow and Sussman have discussed countless ideas for musicals, including one about the cartoon character Betty Boop and adaptations of everything from Mark Twain’s “The Prince and the Pauper” to the movie “Tootsie.” But a musical about the Comedian Harmonists, who were the subject of a documentary that Sussman had watched, was the idea that took hold of both of them.

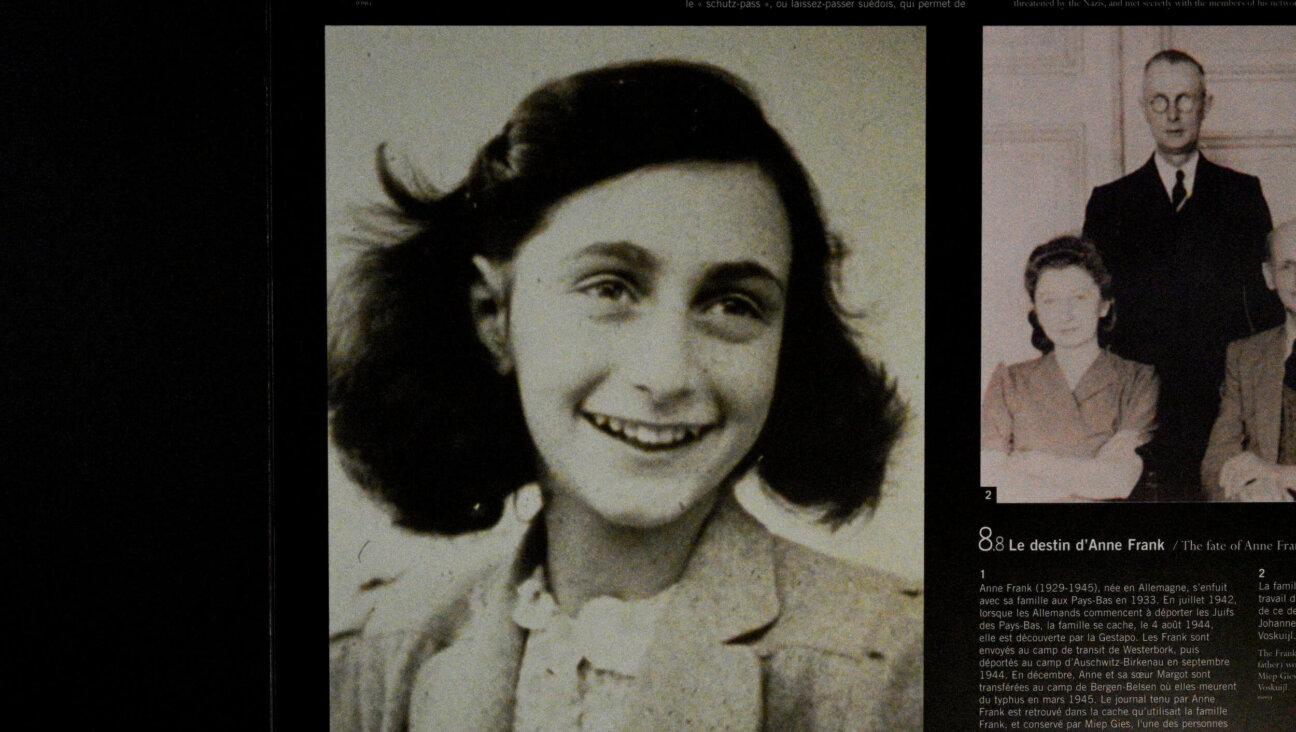

“It’s about a quest for harmony in the most discordant chapter in human history,” Sussman said, though Manilow was quick to add, “It’s not a Holocaust musical.”

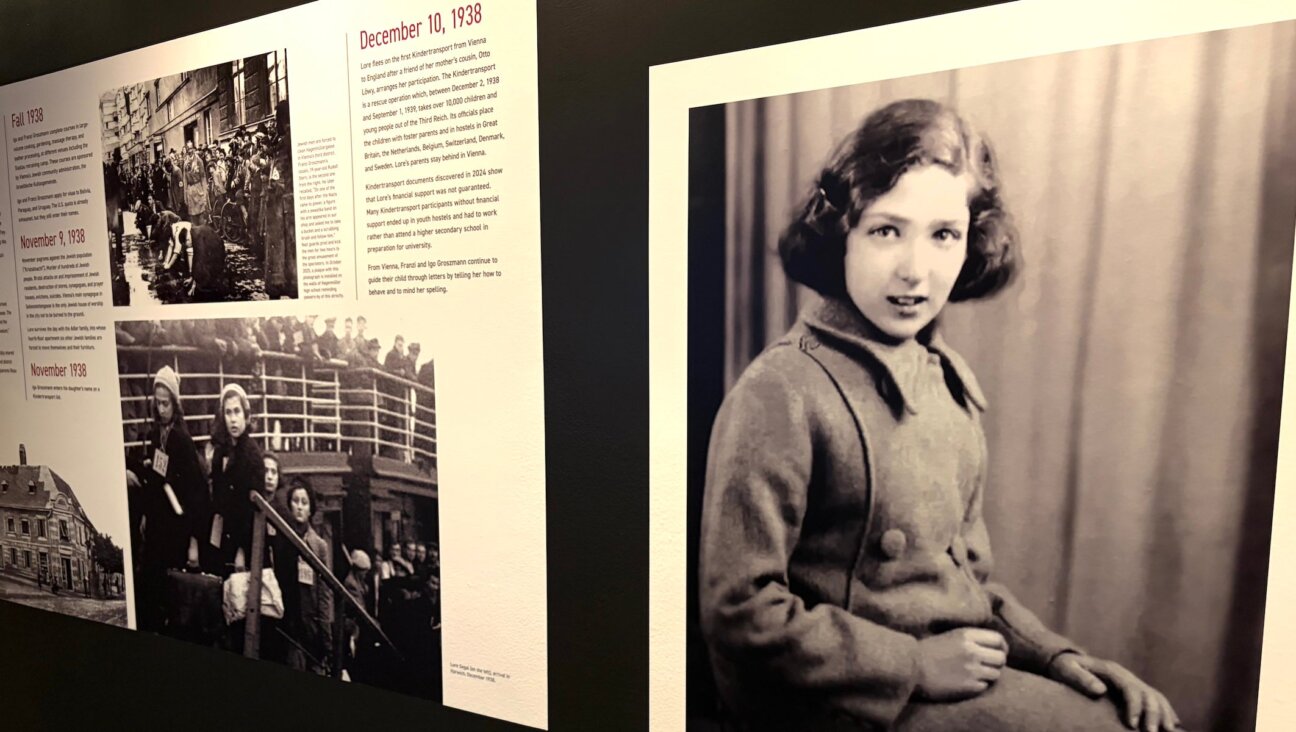

“Right,” Sussman said. “But it takes place in the approaching storm, and I feel that the writing of the play itself is an act of bearing witness, and that’s an important thing to me. We had a survivor come speak to the cast yesterday. She’s 85 and she said something, and I had to bow my head because I was welling up when she said it. She said: ‘I’m 85. How much longer do I have to tell this story?’ I feel that. There has to be another generation who continues to tell the story, who continues to remember. That’s why this musical is so important.”

“The idea spoke to me very quickly. As a musician and as a Jew,” Manilow said. “These guys, the Comedian Harmonists, were the architects of the kind of music that we love today. They were the Backstreet Boys, they were The Beatles, they were huge. Huge. They invented this style of six-part singing. They were young, they were attractive, they were funny. They were revered in Europe. After we saw the documentary, we said, ‘How come we’ve never heard of these guys?’”

“And in a way, that is the story — that we don’t know anything about them,” Sussman said.

Although Sussman and Manilow started talking about this musical in 1991, they didn’t start work in earnest until three years later. Sussman spent a year in Germany doing research before writing a first draft that he says was “longer than Wagner’s ‘Ring’ cycle.”

“It’s been a very rough road for us, but thrilling when it comes to creativity,” Manilow said “Maybe ‘liberating’ is a good word for it. Because I am kind of imprisoned when it comes to the kind of songs that I have to write for albums. There are certain brick walls that I hit. I’ve broken so many rules over the years as a songwriter. But even so, there’s no way I could write anything like what I’m required to write for ‘Harmony.’”

After the initial production, in La Jolla, Calif., Manilow actually got the opportunity to meet one of the original Comedian Harmonists when he was asked to give an award to Roman Cycowski, the last surviving member of the group. Cycowski inspired a character called “Rabbi” in Manilow and Sussman’s musical. He died in 1998 at the age of 97, and had worked as a cantor in Palm Springs and, as it turned out, lived only four blocks away from Manilow.

“I’d been walking the dogs in front of his house for 15 years, and I didn’t even know he was there. He was a vaudevillian, and he still acted like one. During our meeting, he said, ‘If they hadn’t destroyed us, we would’ve been bigger than The Beatles.’”

“I talked to [Cycowski] on the phone,” Sussman said. “He was a character, and he was funny and he was a ham — a kosher one, but a ham. We talked for a while, and I guess his rabbinical training came to the fore; he felt the need to bless me. He said: ‘You know I’m a very old man. I wish you as long and as healthy a life as I have. I hope that you when you reach my age you will still be collecting royalties.’”

“What did you say to him?” Manilow asked.

Smiling, Sussman answered: “I said, ‘A-men.’”

In the Snapple Theater Center, the actors and O’Neill worked out a few rough patches in the musical number they had been rehearsing. O’Neill said that he had decided to use a different chord at the end of a particular phrase. At the table, Sussman looked up from the script he had been studying and asked O’Neill if he was making this change based on something Manilow had suggested.

“Yeah,” O’Neill said.

Sussman nodded as if to say that this was the only thing that mattered — “Okay” — and then he went back to his script.

“All right,” O’Neill said. “Let’s call Barry in.”

Moments later, Manilow strode in with the assurance of a man used to being the center of attention in any room. The men stood upright, then turned their attention to their scores. O’Neill began to play.

“Harmony,” the Harmonists sang. “We sing in harmony. Like the robins in Leicester Square — Tweedle dee, tweedle dee dee dee dee dee.”

Whether they actually sounded like robins is open to some debate, but the harmony did, in fact, sound perfect. Manilow seemed to think so, too.

“You guys sound great,” he said as he started to head for the door. “You’re beginning to sound like a real group. We’re almost there, guys. We’re on our way.”

Harmony opens on September 6 and runs through October 6 at the Alliance Theatre, in Atlanta.

Adam Langer is the arts and culture editor of the Forward.