Turning to Day Schools When Synagogues Just Won’t Do

Working Model: Day Schools are serving needs that synagogues simply aren?t anymore. Image by Getty Images

My name is Ken Gordon, and I don’t belong to a synagogue. When the Pew Research Center reported that two-thirds of American Jews are in the same situation, I didn’t break out into a cold Jewish sweat, as did so many of my colleagues. I thought instead: I’m not alone!

My wife and I send our kids to a Jewish day school. It’s an intense, joyous, valuable experience, and that’s really all we need or want. It’s our Jewish institution of choice. Period.

Recently, a rabbi tried to change my point of view. She basically tried to guilt me into joining her synagogue. I had inquired about doing an independent bat mitzvah for my daughter.

“We often find that day school families are looking for a community and clergy connection that complements the deep sense of community experienced at day school,” she wrote in an email. “We also know that (most unfortunately!) day school years do not last forever, and it is important to establish communal Jewish connection post b’nai mitzvah and post day school.”

At first, this infuriated me. It implied that I was cutting my kid off from Jewish life, that the only road to communal participation was through membership at a synagogue — and that day school was, at best, a short-term investment. In other words: I was walking my little girl down the royal road to assimilation.

The email didn’t change my mind — in fact, it made me that much more determined to figure out an alternative way to make an independent bat mitzvah happen — but it did suggest something to me: Day schools don’t last forever, but they should.

Here’s the typical pattern: Parents send their kids to a day school. The kids graduate. The parents become uninvolved. The kids, well, they grow up. They get married, have kids and, if everything goes as hoped, send their children to day school.

This is a flawed model. The huge gap in a family’s active day school engagement is one reason that schools face such serious sustainability issues, and why they serve only a small fraction of the population. The solution to this problem — and perhaps to the problem of Jewish day schools in general — is that the schools need to think bigger.

Jewish day schools could be, like synagogues themselves, for the entire Jewish community. They should be the place where people come to study, a home for everything from early childhood education to traditional day school study, b’nai mitzvah prep and adult education. Imagined this way, day schools would have a much larger base and a much greater opportunity to build lifetime relationships. Why shouldn’t day schools take the lead in lifetime learning?

I can easily imagine how a day school might open its doors to the community. Not just obvious stuff like text study with the great Judaic studies teachers on staff, or “Hebrew for Hebrew School Dropouts” (given by the parents whose lousy Hebrew school educations prompted them to choose day school for their own kids). Why not do a lecture series using the smart writers and professors in your local community? Why not bring in the business owners and entrepreneurs to talk innovation? Why not provide professional development and networking classes to people in your community who might need them? How about robust after-school programs? On-campus camping?

Some might think that I’m suggesting we turn a day school into a Jewish community center. Not so. Yes, JCCs do offer education for the community — but day schools are different. They are dedicated to education in a way that community centers, with their wider mandate, are not. Day school students spend half of each day speaking and living Hebrew. Does that happen at your local JCC? And it’s also a matter of time. At a day school, kids are in a Jewish — and not necessarily a religious — learning environment all day long, five days a week. The day school experience is an all-out Jewish experience, one of the few that our kids will ever get while walking on American soil.

The question of cost will inevitably arise, as day schools have a reputation for being unaffordable to many. Should a school give away all this after-hours learning for free? That’s not what I’m suggesting. It might be feasible to offer a carefully selected activity or two to the public gratis — the value of getting certain prospective parents or families in the door might outweigh the lost revenue — but in general, one would expect schools to charge a fair price for the high-quality learning experiences they offer. I leave it to individual schools to crunch the numbers and determine just what parents can afford to pay. Perhaps a local donor or two, sensing that the community is already overburdened, might want to help by subsidizing some adult education. Remember, I’m suggesting that day schools will provide the services that synagogues are not — and think of what people pay for synagogue memberships just so they can go to the High Holiday services twice a year.

The secret sauce here will be synagogue-averse Jews. For them, congregational life isn’t part of the equation. While they won’t be swayed by a religious appeal, they just might go for a cultural one. An intellectual one. If these people were keyed in to the close, warm learning communities that day schools embody, it just might change the way in which Jewish life in America constitutes itself.

What would it take to expand our day schools’ area of operation? It would take some smart, vigorous programming. It would take people who understand local social networks. And it would take visionary educators who see why daring to place learning at the heart of Jewish life is exactly what’s needed right now.

Ken Gordon is the senior social media manager and content strategist of the Partnership for Excellence in Jewish Education. He’s also a co-founder of JEDLAB, a network of Jewish educators.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

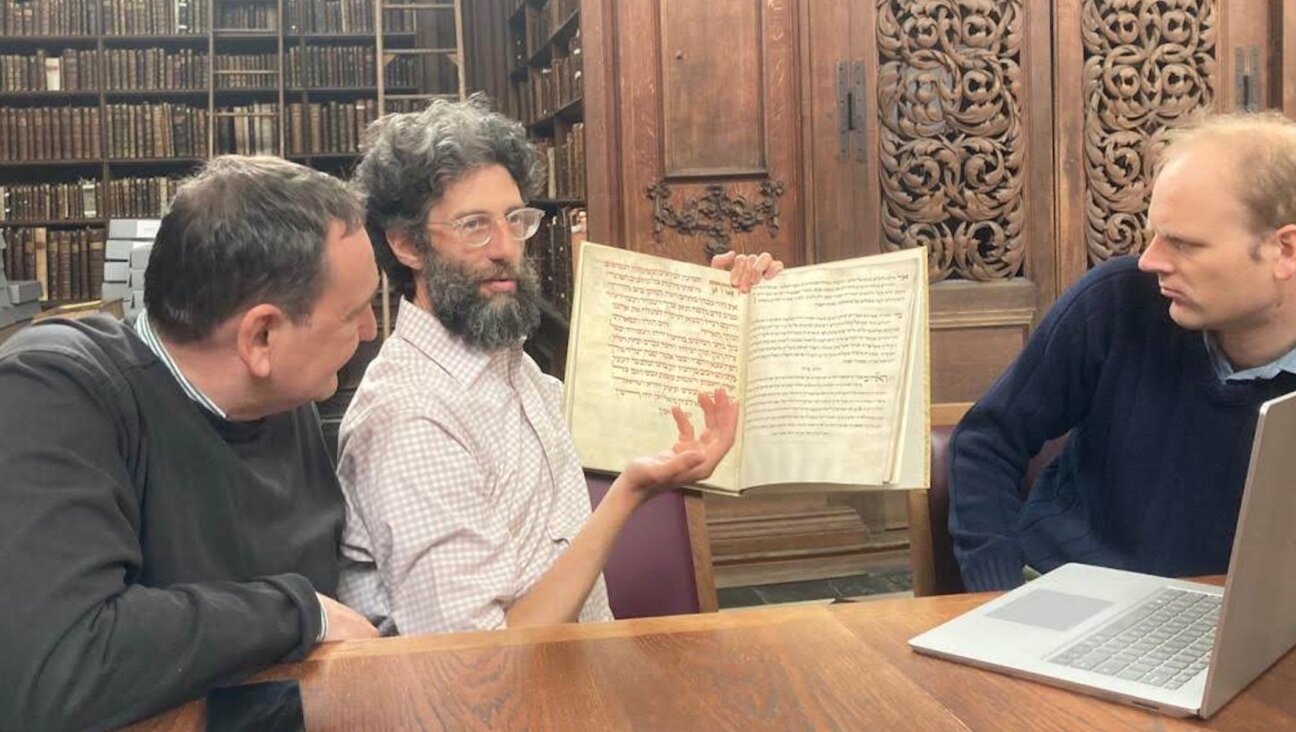

Fast Forward For the first time since Henry VIII created the role, a Jew will helm Hebrew studies at Cambridge

-

Fast Forward Argentine Supreme Court discovers over 80 boxes of forgotten Nazi documents

-

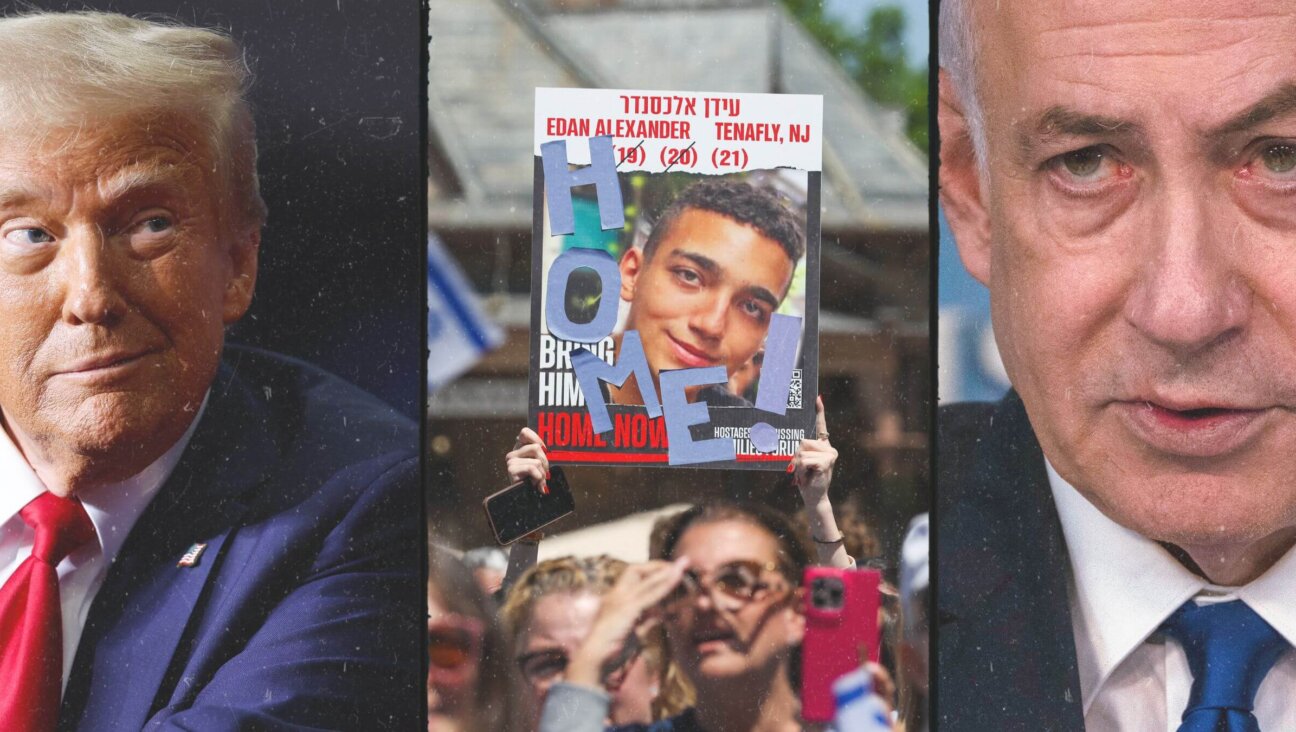

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.