When Jews Found Refuge in Pakistan

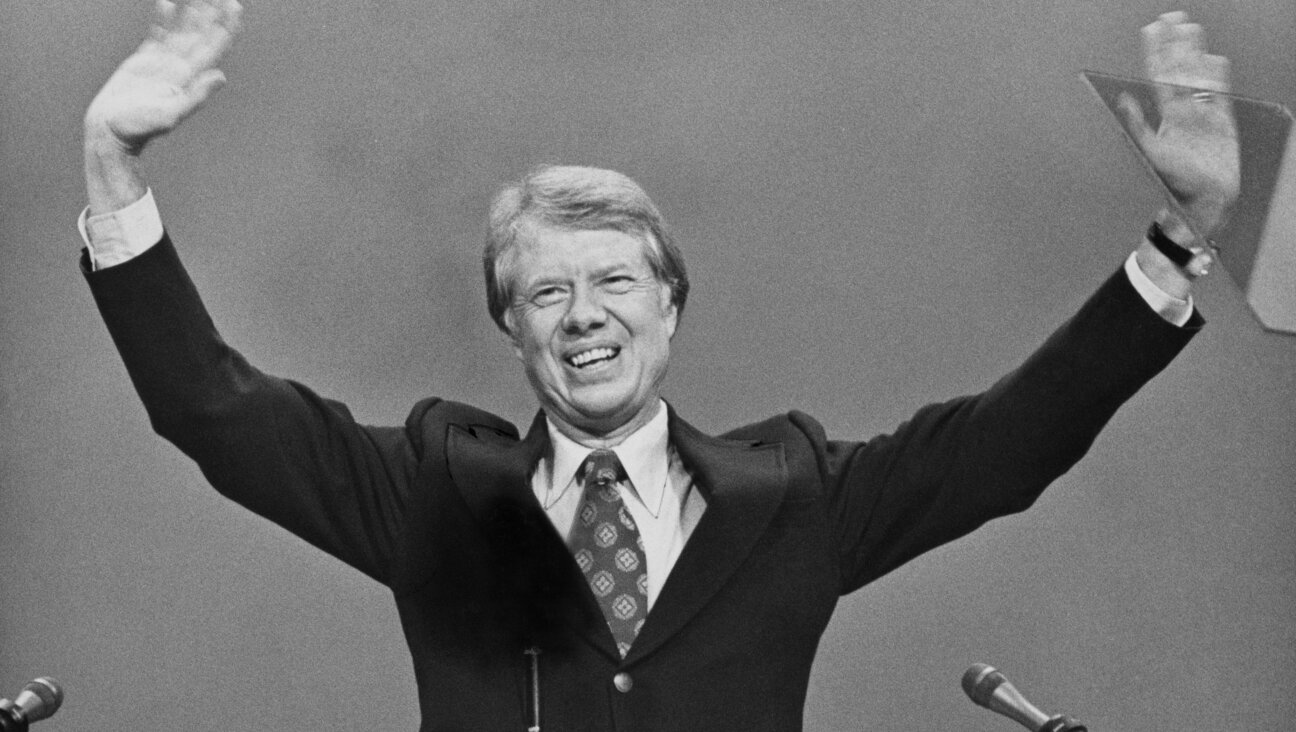

Not Your Typical German Anti-Nazis: From left, Hazel Kahan, her mother Kate, and her brother Michael, in Lahore, Pakistan, in 1948. Image by Courtesy of Hazel Kahan

When Hazel Kahan went back to Lahore, Pakistan, in 2011 for the first time in 40 years, her childhood homes were completely different. Her first home, formerly a tan stone mansion covered in flowery vines, was now completely painted in white and inhabited by the Rokhri family, one of Pakistan’s most powerful political clans. Her second home, where her parents had run a medical clinic, had become the Sanjan Nagar Institute of Philosophy and Arts.

After living in England, Australia and Israel, and having worked in market research in Manhattan for years, Kahan, 75, now lives in Mattituck, on the North Fork of Long Island. She produces interviews for WPKN radio in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and has recently begun discussing her family history in public presentations, telling a story that illustrates how complicated citizenship and allegiances were for Jews during and after World War II in Pakistan and beyond. She has presented her piece “The Other Pakistan” in Woodstock and Greenport, New York and twice in Berlin. She plans to bring her performance to Montreal in November.

“I never really cared about it, I never bothered, until [my father] died [in 2007],” Kahan said of the project. “Then I realized there’s no one left to tell this story. He did his best to pass it on to us. And we’re responsible, you know?”

The story begins in 1933, when Kahan’s parents, Hermann Selzer and Kate Neumann, left Nazi Germany separately for Italy, where Jews were allowed to study medicine. Hermann and Kate (who had briefly met in Berlin years before) met again in Rome and married in 1935. As Europe became increasingly dangerous for Jews, they decided to leave the continent. Most Jews migrated to British-controlled Palestine, but Kahan’s parents made their decision of where to go on a whim. At a dinner party in Rome, an Italian monsignor suggested that they move to Lahore, Pakistan, which was then still part of British India and a city that had an exotic reputation as a crossroads for travelers and traders.

“He said to them: ‘Why are you thinking of going to Palestine?’” Kahan said. “‘You’re young, you’re cosmopolitan, you have medical degrees; in India they need European doctors. Go to India.’”

It turned out to be a great decision — at least for a while. Kahan said that her parents were graciously welcomed in Lahore. They set up a successful medical practice, and her father became part of the British elite class. Lahore was a worldly city with a vibrant international culture.

“Lahore was a very special place because it was at the crossroads of a lot of trade from the East going to Iran and Turkey,” Kahan said, who was born there in 1939. “So people came through and the whole place became a room for travelers.”

That didn’t mean that there were a lot of Jews in Lahore. In the 40s, around 2,000 Jews lived in Pakistan, and most of them were settled in the port city of Karachi.

Kahan’s family lived a largely secular life. For Passover, Kahan recalls eating chapati (more commonly called roti), the unleavened flatbread found throughout India and Pakistan, without really knowing why. The annual sign of Yom Kippur was her father’s fast, which gave him a headache each year.

“It’s kind of difficult to be a Jew if there are no Jews around,” Kahan said.

In December 1940, in the early stages of World War II, Kahan’s family was forced by the British-Indian government to move to internment camps in Purandhar Fort, and later in Satara, in the southwest of India. This happened because the Selzers were “stateless,” and thus considered enemy aliens by the government. Poland had passed a law in 1938 that revoked citizenship from any Polish citizen who had been abroad for at least five years. The Selzers fit this description: Hermann was born in Poland, but his family had moved to Oberhausen, Germany, when he was a child. Kate was born in Germany but assumed Polish nationality when she married Hermann. They had Polish passports to travel to British India, but ceased to be citizens of Poland after the new citizenship laws took effect.

“I think there were maybe like 200 families [in the interment camp],” Kahan said. “They were classified as German Nazis, German anti-Nazis, which we were, and then Italian fascists. So the camp was kind of divided in that way, and we were lopped in with the German anti-Nazis, who were mainly missionaries.”

In the internment camp, the family had a house and lived a relatively normal life under supervision of local officials for five years. Nevertheless, the Selzers had to abandon their medical practice and move away from Lahore. Most interned families faced financial hardships. Their relations to the government and those around them inevitably changed.

In the internment camp, Hermann Selzer began to write down his experiences. He continued to write until he had a stroke, a few years before his death in 2007. Many of his writings, in addition to a collection of his letters, legal documents, and photographs from the 40s through the 60s are now archived on microfilm at the Leo Baeck Institute, a research library of German-Jewish history housed in the Center for Jewish History in New York. Selzer never published any of his work.

“He was a very disciplined man,” Kahan said of her father. “And I bought him a typewriter. He sat writing every morning and then I bought him an electronic typewriter, and he wore it out so I bought him another one.”

After the war ended, the Selzers moved back to Lahore and restarted their practice. By the Six Day War in 1967, relations between Jews and Muslims had soured (Pakistan is home to the second largest Muslim population in the world). By 1971, the atmosphere had gotten so tense that the Selzers decided to move to Israel. Kahan said that her parents wanted to spend their entire life in Pakistan, and dreamt of dispensing free medical care to people throughout the Middle East after they retired.

“But being Jewish was no longer being Jewish, it was being Zionist,” Kahan said. “And that was the problem.”

In Israel, Hermann worked part-time at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem and kept writing. By this time, in a testament to the international turmoil they lived through, the Selzers had accumulated four passports: They had retained their Polish passports, earned Pakistani passports, were given German passports after the war (as a recognition of suffering, Kahan explained), and obtained Israeli passports upon settling in Jerusalem.

Decades later, Kahan went through her father’s letters and documents and wrote two unpublished memoirs — “A House in Lahore” and “An Untidy Life” — about her childhood; both were subtitled “Growing Up Jewish in Pakistan.”

The title of her new presentation, “The Other Pakistan,” refers to the seemingly unexpected hospitality and warmth that she has repeatedly experienced as a Jew in a predominantly Muslim country. (Today, at most 800 Jews live there.)

“Pakistan is obviously a really horrible country, with everything bad from Taliban to whatever you want to say,” Kahan said. “But the point is for me is that the other Pakistan is this hospitable place.”

Despite having gone to boarding schools in England and living in various other countries throughout her adult life — not to mention being forced to live in an interment camp as a child — Pakistan is still close to Kahan’s heart. She explained that she has been graciously welcomed back into the Pakistani community every time she has visited.

“I feel because I was born there that in a very profound way it’s my home,” she said. “Even though I’m not of it, I’m from there.”

Gabe Friedman is the Forward’s arts and culture intern. Contact him at [email protected]

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO