The Shadow of God

The details of the building of the tabernacle are relentlessly mundane, and we read them trusting that they might perhaps be of interest to a committee of architects, accountants and engineers whose arcana we have never studied and whose work is utterly mysterious to us. “And of the thousand seven hundred seventy and five shekels [of silver] he made hooks for the pillars, and overlaid their chapiters, and filleted them (whatever chapiters are and whatever filleting is)?” Good! Some of these are words that smart people do not know in English, let alone Hebrew. “And the two ends of the wreathen chains they fastened in the two ouches, and put them on the shoulder-pieces of the ephod, before it.” What are ouches? What does any of this mean? And why are we being told these things in such overbearing specificity?

For some readers, these spec sheets and ledger details are opaque and intimidating. For others, there is a poetic effect that works rather in the way that the catalog of ships does in the second book of “The Iliad,” where the barrage of proper nouns becomes, as Auden noted, a touchstone of aesthetic experience. There the names of places and of warriors, though not perhaps individually interesting, cumulatively change in a quite fundamental way and for some — for those whom Auden calls the natural readers of poetry — start to resonate. There can be a realization that this is not mere literature but a national epic, a celebration of a culture and a people, and that it is serious, in a way no “mere” poem pretends to be. Here, too, at the end of the Book of Exodus — in this week’s portion, Pekudei — there is a cumulative effect, and then, at the end of the portion, a dramatic transformation such as not even Homer could have imagined, for at the conclusion of the passage, Moses completes the project. “Then the cloud covered the tent of the meeting, and the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle.”

I cannot help but see the passage as a demonstration of the transformative power of art, the elaborate technical instructions having the dry-as-dust matter-of-fact quality we recognize in any critical discussion of craftsmanly technique — in painting, architecture, poetry or the decorative arts. From these technical details, we take a kind of reassurance that, yes, this is how it was, these were the materials and the methods, and we have the sense that, with care and attention, the project could have been done — or even the illusion that, with these things at hand, we might be able to do something like it ourselves. The encounter is like what we experience looking at a display of a writer’s manuscripts, where the corrections and emendations are there for us to examine, with all the false starts that are crossed out, and we can glimpse in the exhibits in the glass cases some suggestion of the creative process and even persuade ourselves that we understand how it was to write that story or poem. (We have seen draft versions before of these details of the tabernacle, in the portions Terumah, Tetzaveh and Ki Tissa, but this is where those promptings are realized.)

What we find here is the mysterious dialogue between thought and action, between intention and execution. Robert Frost said, “No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader,” and what he meant by that is that the realization ought to be startling and better than the poet could have imagined when he began. In these lists of methods and materials we read at the end of Exodus, there is, like a refrain, at the end of each paragraph in Chapter 39, the necessary qualifying phrase: “as the Lord had commanded Moses.” Again and again, that phrase reminds us that the artisans are instruments of the work as much as they are its authors, and they are discovering the meaning and the rightness of the plan. Nineteen times it echoes and re-echoes in our ears and our hearts. Without the commandment of the Lord, all the topazes, carbuncles, emeralds, sapphires, amethysts and diamonds are just so many stones in a jeweler’s pouch, rare maybe and pretty perhaps, but not with the importance they acquire when put to use according to the commandment of the Lord.

It is hardly an accident that the chief craftsman on this job, the one who is carrying out the work, is Bezalel, whose name, b’tzal-El, means “in the shadow of the Lord,” for the making of the tabernacle is a creation, and as the artist’s name proclaims, any creation is inevitably in the shadow of the Creator. And, as if in answer to the “shadow,” the success of the work is demonstrated at the end of the portion when the presence of God (k’vod El — or “glory” or “light” of God, as it is sometimes translated), signifying approval, enters the tabernacle and fills it.

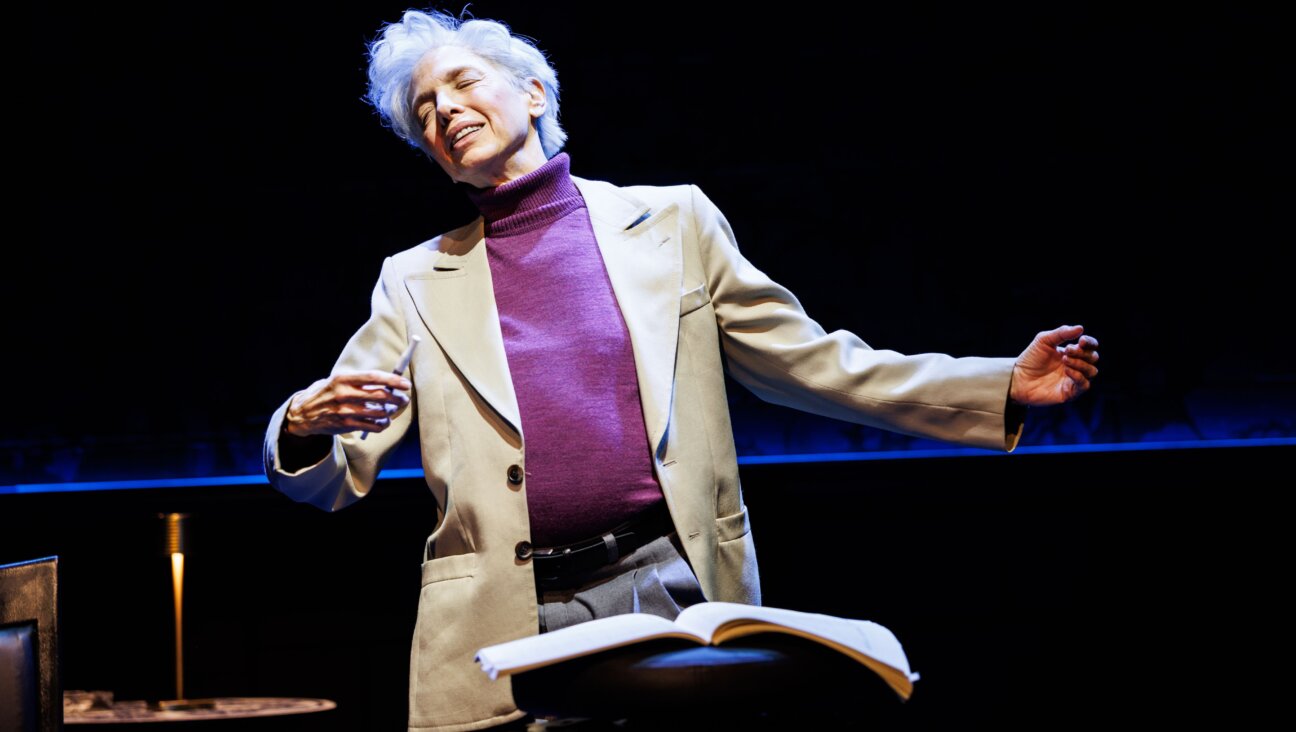

David R. Slavitt’s new collection of poetry, “Change of Address: Poems, New and Selected,” will be published this spring by Louisiana State University Press. It will be his 80th book.

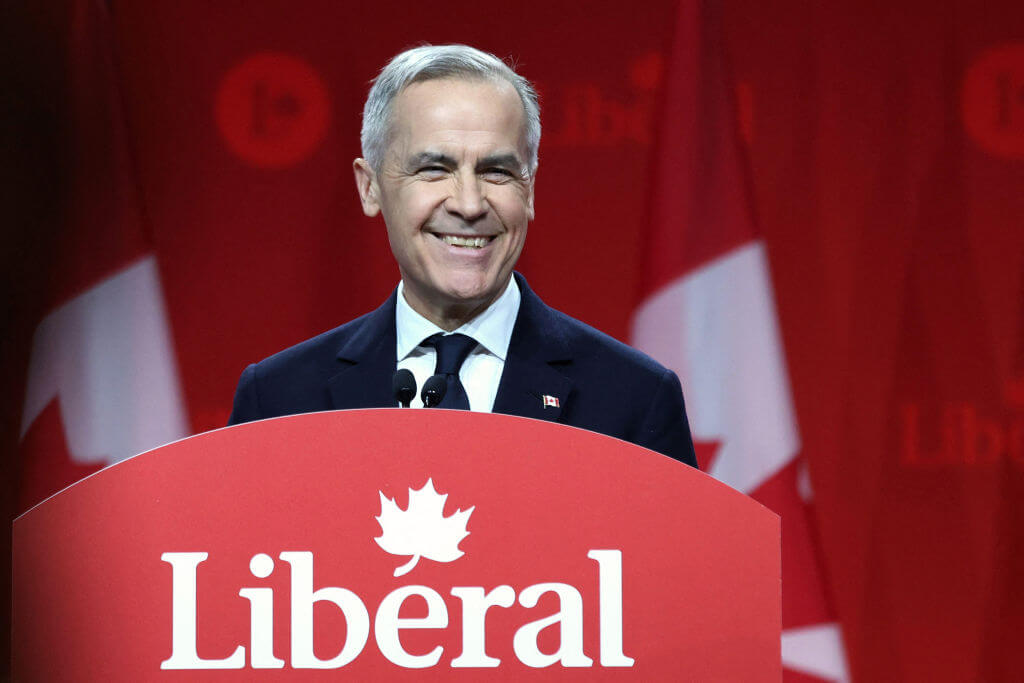

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO