An Autobiography in Pictures

It’s possible that Sylvia Plachy missed her calling. The distinguished photographer, for many years my elusive colleague at the Village Voice, is also a gifted storyteller; her words and images (along with pictures from her family album) combine to remarkably poignant effect in “Self Portrait With Cows Going Home” (Aperture, 2004), an autobiography of sorts, and an ode to both the exile’s life and the land of her birth.

Plachy means “shy” in Czech; 12-year-old Sylvia is the girl in the front row with her toes turned inward in her 1955 class picture from Budapest, Hungary, the city of her birth. One year later, following the brutal Soviet clampdown on the Hungarian Revolution, she slipped out of the country with her parents, clutching a toy monkey inside of whose belly (unbeknownst to her) someone had sewn the remnants of the family fortune — gold coins and a bracelet.

The Plachys waited more than a year in Vienna for visas to America, where they arrived in 1958, first settling in the promised land of New Jersey, and later moving to Queens. Sylvia was 21 and already a photographer when she made her first trip back. (Her mentor, honorary grandfather and fellow Hungarian Andre Kertesz, took her picture — young and solemnly beautiful —in his Fifth Avenue apartment on the eve of her departure.) A black-and-white photograph she took in 1964 shows the breakfast of bread and jam — served on old family china and with the Hungarian newspaper neatly folded on the tablecloth — which her 92-year-old grandmother (who had stayed behind in their former apartment) prepared for her each morning of that return visit.

In the mind of the exile, home remains unchanging, an image fixed at the point of departure. For those who left countries stranded behind the Iron Curtain, this illusion was still more powerful. While the West pursued its headlong rush forward, everything there, from the make of the cars on city streets to the geese for sale in the markets and the cows ambling down village lanes, remained imbued with the aura of times past.

On successive trips back to Hungary and while traveling (sometimes on journalistic assignment) through other countries in the Eastern Bloc, Plachy’s camera captured these traces of her real and imagined childhood with extreme tenderness and yearning, even as it also noted the fallout from the great socialist experiment then unfolding — the architectural nightmares of Ceausescu’s Romania, for example, or the bear cub looking up (in fear?) at his attendant in Budapest Zoo. (Plachy’s accompanying text explains that in the zoo at that time, baby animals were taken from their mothers during the day and put with the young of other species; men in green coats bottle fed them; many animals sickened and died.)

She was also there in later decades, to record the Socialist Realist monuments as they fell; the empty frames in bureaucrats’ offices that formerly held pictures of dictators; two Berlin teenagers pretending to be executed against a remnant of the wall.

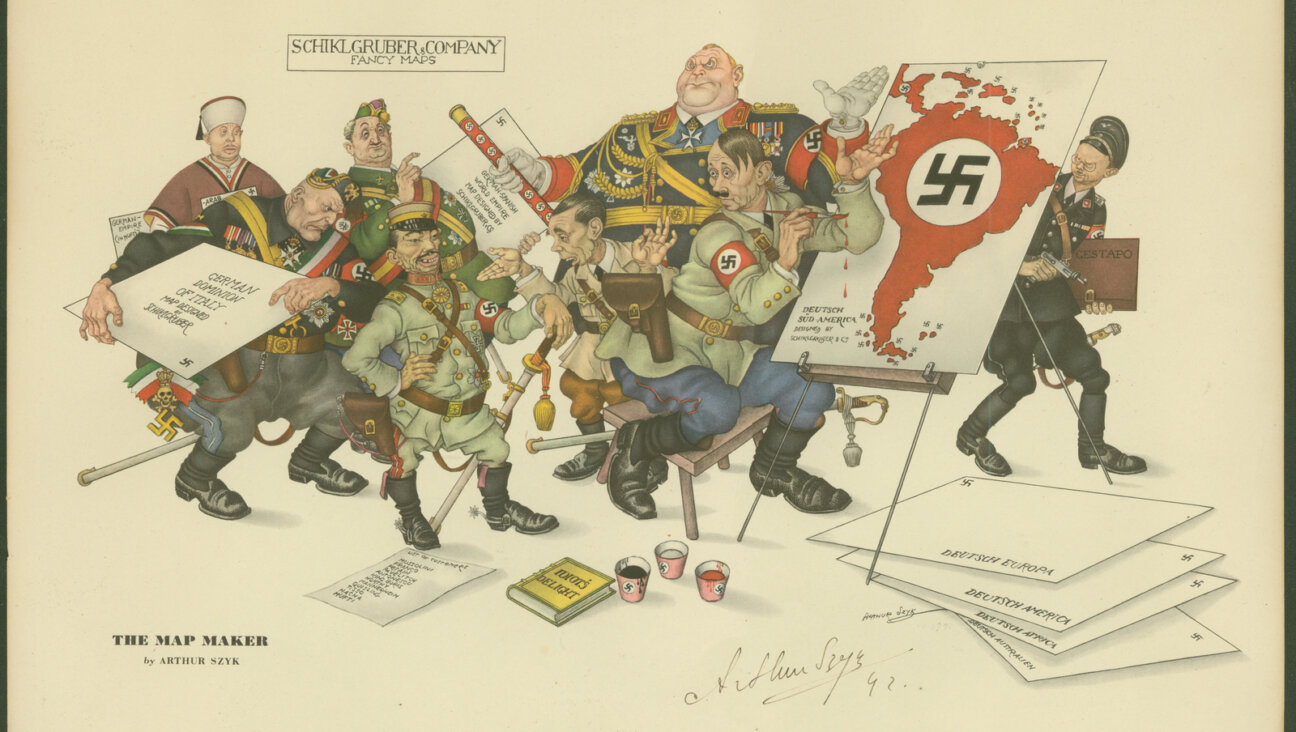

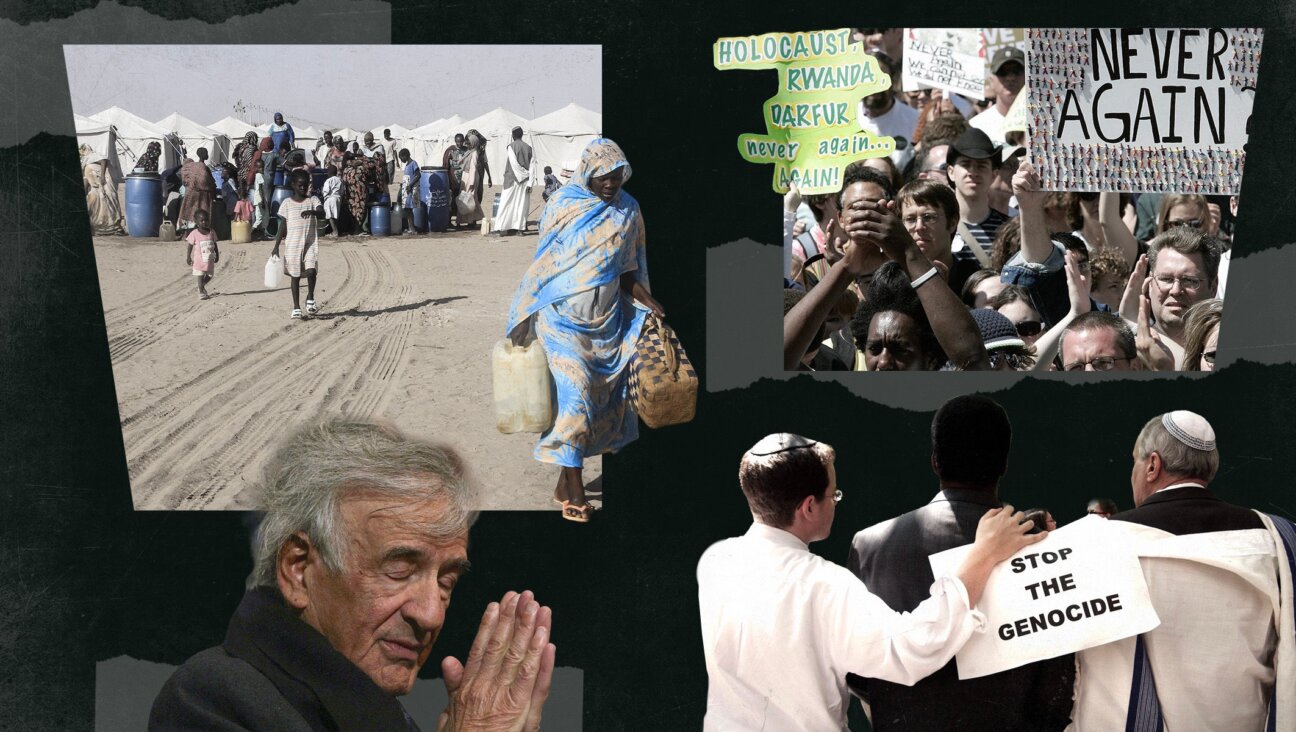

Woven into this world historical saga is the story of Plachy’s family. Her handsome Hungarian Catholic father, fruit of her impoverished, aristocratic grandmother’s ill-fated affair with a guard in the Hapsburg court, married her mother, a Czech Jew, on the eve of World War II. (Hers was a wartime birth: The announcement from 1943, etched by her father, shows a naked baby parachuting toward a globe in flames, and her first words mimicked the sound of falling bombs.) Plachy’s maternal grandparents, a prominent lawyer and his wife, were deported along with Plachy’s aunt from their village in Czechoslovakia to Auschwitz; only the aunt survived.

During the postwar years in Hungary, Plachy’s mother kept her own Jewishness a secret while Plachy, rebellious and dreamy, took refuge in a kind of renegade Catholicism. Today, her mysterious images of a Romanian hermit, a haunted tree or two yoked horses heading down a muddy, winding path suggest a soul still seeking its spiritual homeland. Her portraits of animals — a dancing bear, a gypsy dog — are among her most compelling, as vividly drawn as creatures in an animist folk tale.

Plachy’s Jewishness comes back to haunt her in images of her son, actor Adrien Brody, who won an Oscar for his starring role in Roman Polanski’s Holocaust drama, “The Pianist” (2002), based on the true story of Wladyslaw Szpilman, a Polish Jewish musician who survived the war by hiding out in Warsaw. Plachy juxtaposes pictures of Brody in period costume and of the film’s set in Poland with the story of his great-grandparents’ deportation, as if the seventh art possessed some magical power to conjure the ghosts of missing family members. Having considerably less faith in movies, I prefer the photographs of Plachy’s son at age 3, on a trip to Hungary, where he pretended to shoot at everyone while shouting, “Bang, bang! I’m an American cowboy.” Between these two poles, of longing for the past and insouciant acknowledgement that it is gone forever, her own art unfolds.

Leslie Camhi writes about the arts The New York Times, the Village Voice and numerous other publications.