Children Forced To Become Killers, Sex Slaves in Forgotten Uganda War

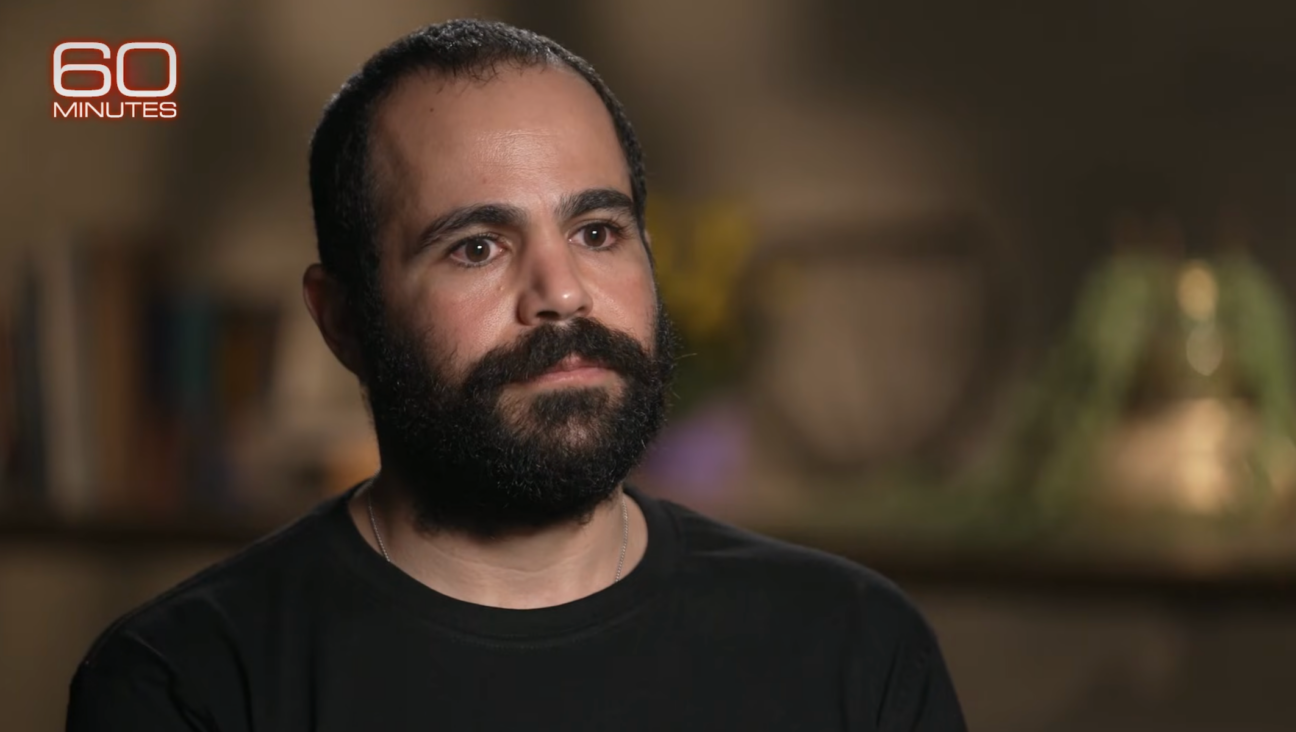

GULU, Uganda — It is much harder, Nelson Oyet explains in a monotone, to hack a child with a machete than to shoot him with a gun. He is 16.

Jennifer Atira recounts in a halting voice how she was given as a “wife,” at 13, to a commander twice her age who would beat her if she refused to sleep with him. She is glad he was killed. She is now 15.

Ronaldo Mwaka is a “night commuter.” To avoid abduction from his isolated village by rebel recruiters, he sleeps in an urban shelter every night and returns to school at dawn. He is 13.

These children and thousands like them are the most poignant legacy of a little-noticed civil war that has shattered the lives of the Acholi people of northern Uganda for almost two decades.

While worldwide attention has been focused on the Darfur region in neighboring Sudan, Acholiland has been wracked by “the most forgotten crisis in the world,” as Jan Egeland, U.N. undersecretary general for humanitarian affairs, put it during a visit in 2003.

This is not a classic war featuring armies and a front line. Nor is it a conflict fueled by natural riches, as in neighboring Congo. This conflict pits the Ugandan army against the Lord’s Resistance Army, a movement that started in the mid-1980s to defend Acholi rights, but morphed into a murderous, cultlike group under the mystical spell of LRA leader Joseph Kony.

Kony’s army is estimated to have abducted some 20,000 children, handing girls to its commanders as sex slaves and training boys to kill, maim, rape and loot.

And children are not the only victims. The United Nations estimates that fully 80% to 90% of the inhabitants of Uganda’s north, some 1.6 million people, have been forced out of their villages and into so-called internal displacement camps. There are some 130 such camps, woefully lacking food and sanitation, much less education and jobs.

Despite its Christian leanings, Kony’s group won backing in the mid-1990s from the Islamic fundamentalist regime in Sudan. It was a tit-for-tat gesture, payback for Uganda’s support of a long insurgency in southern Sudan.

Fighting has slowed in recent months as the LRA has been weakened militarily and peace talks have commenced. Observers say, however, that mutual mistrust is hampering progress. The rebels also fear prosecution by the newly formed International Criminal Court, which has taken up the Ugandan conflict as its first case.

Regardless of the talks’ outcome, the conflict will leave deep physical and psychological scars in a long-neglected region. “The LRA is no longer a political or military force, but the criminal energy is still there,” said a Western diplomat in Kampala, the Ugandan capital.

Over the past decade, 9,000 child soldiers who fled the war or were captured by the army have passed through a rehabilitation center here, run by World Vision, a California-based Christian group. The center provides basic psychological care and helps reintegrate the children into their communities.

Nelson Oyet, the 16-year-old machete veteran, arrived here this past October after spending seven years in the bush. He had fled during the fog of a chaotic battle.

He vividly remembers the day, December 28, 1997, when four young rebels raided his remote village, ordering him and his older brother to come with them. They spent weeks in the bush, where Nelson was forced to watch abducted children, including his brother, kill other children who were caught trying to escape. It was a standard rebel method of disciplining recruits.

After three months, the band crossed into Sudan and underwent basic military training. And so began years of assaulting villages, fleeing army attacks, and fighting starvation and cholera.

Nelson said he killed 10 fellow rebels who tried to escape — six with a gun and four with machetes, “the most painful.”

“I had to kill some friends,” he said. “I had no option. I had to kill to stay alive. I feel bad about it. I used to have nightmares about it, but less so now.”

He spoke for three hours in Lwo, his native language, through an interpreter, in a low voice — his round face showing little expression. But the language of his bulky body — legs swinging back and forth, fingers nervously drumming on the wooden table in front of him — betrayed his emotions. Tears finally came when he recalled reuniting with his father this past November.

Kevin Okwoy, a camp psychologist, said that Nelson had recovered from his emotional trauma and would be returned to his family soon, possibly early this month.

But the reunions are not a simple matter. Communities are often loath to accept the young killers. “We need to sensitize the communities about the plight of those children,” said Sam Kilara, World Vision’s outreach coordinator in Gulu. “We tell them: Those children were once yours, and they are lucky to be back. Forgive them.”

There are other problems for so-called child mothers, such as Vicky Achan, 21, and Grace Apiro, 23. They worry that the babies they bore — both with the same rebel leader — never will be accepted by their families. Vicky wants to hand over her 18-month-old to the father’s clan and start over.

Nelson said that he would like to become a “manager,” but he still fears being abducted again and killed. He is still scared of Kony.

He is not the only one. One reason for the LRA’s durability is the widespread belief among Acholis and even government troops that Kony has supernatural powers.

Kony started his Lord’s army in 1987, taking up the mantle of Alice Auma “Lakwena.” She led a failed Acholi rebellion against government troops in the mid-1980s after announcing that she was possessed by a Christian spirit (Lakwena, a dead Italian soldier) to bring justice to the region. Kony is said to have claimed that he was chosen by God to implement the Ten Commandments, although he retains various local rites and rituals and is said to have at least 40 wives.

Even in this largely mainstream Christian country — Uganda is about 45% Catholic, 35% Anglican and 15% Muslim — Christian leaders say that dispelling Kony’s aura of divinity is a daunting task.

Following a major Ugandan military offensive inside Sudan in the spring of 2002, the rebels moved en masse into northern Uganda, prompting panicked villagers to stream into the camps. The camps’ population quadrupled from 400,000 to 1.6 million.

The largest of the camps is Pabbo, some 50 miles northwest of Gulu, where more than 63,000 people are crammed into rudimentary thatched-roof adobe huts.

Inside one round hut, Parasesta Akumu was breastfeeding Vicky, age 2. Sitting on the dirt floor near a small fire stove, she explains softly that Vicky, the youngest of her 10 children, suffers from malaria. The children all sleep with their parents in the tiny space — 12 feet in diameter — amid pots, bowls, grain bags and mattresses. The creaking wooden door is plastered with World Food Program stickers, a reminder of the critical role the United Nations agency plays in feeding the camps of northern Uganda. Parasesta, now 40, has been here since the camp opened in 1996.

In addition to malaria, diarrhea, AIDS, eye and skin infections, respiratory diseases and malnutrition, most feared are the cholera outbreaks that sweep the camp periodically. Alfred Okweza, head of one of the camp’s two overcrowded “health centers” — simple concrete structures with no beds — says the situation is “not good.” Still, he adds quickly, everyone gets minimal treatment, with the help of international relief groups.

Despite government claims that the camps are the best way to protect civilians, human rights groups contend that Uganda’s poorly trained, low-paid troops don’t offer much protection. Indeed, soldiers themselves are accused of atrocities against civilians, including murder, torture and rape.

Alexander Oleima, the camp’s government security officer, claims that the abuses have decreased in recent months and that security in the camp has vastly improved, thanks to the troops’ redeployment farther away from the camp. Now, he says, violent incidents only involve men venturing outside the security perimeter to fetch firewood for their families. Each year, wood gatherers have to venture farther and farther from camp to find trees that are still standing.

Michael Owondo and his wife, Aci, were inside their hut at the edge of the nearby Jenagari camp when they met their fate January 27, shot by rebel raiders, according to camp chairman Albert Ochaliam. In the hut are metal and plastic dishes and mugs riddled with bullet holes. A large spot on the dirt floor is darkened with dried blood.

But the camp is still safer than the countryside, and people have continued to stream in since Jenagari opened last year. Its population now tops 2,000. Adere Ouma, a genial 54-year-old, says he came to Jenagari from Pabbo to be closer to his village.

“Going back to the village” is an oft-repeated hope in this rural land-locked country of 25 million — once proposed by the British as a homeland for the Jewish people. Acholiland was for years Uganda’s breadbasket, known for plentiful crops of sorghum, millet, tea and coffee. Today the fields are largely abandoned and overgrown.

While one-third of Ugandans live below the poverty line, the proportion in the north is two-thirds. The war has forced about half the schools in the region to shut down. The literacy rate is below 50%, compared with 65% nationally.

Many children do not attend school. Groups of school-age children can be seen running around naked or barely dressed, surrounded by dogs, ducks and pigs, playing in filthy water amid the charred remains of burned-down huts.

Other children go to great lengths to get an education. Among them are tens of thousands of “night commuters,” village children who slip into the larger towns every night to avoid abduction. They sleep in the streets, in churches and, increasingly, in night shelters set up by human-rights groups.

Ronaldo Mwaka, Alfred Arop and Stephen Onek, all teenagers, come to Gulu every evening from the neighboring village of Alen to sleep in a shelter. They head home for primary school at 5 a.m. “We are afraid in the village,” Ronaldo said before racing off with his companions to make the 9 p.m. curfew.

The impact of the war on children, as well as the LRA’s gruesome crimes — in addition to killing, the rebels favor cutting off lips, ears and other body parts — has alienated the group from the population it vowed to defend when it emerged in the mid-1980s.

Still, the region’s long-standing grievances toward the central government in Kampala fester on. Acholis claim that they have suffered systematic discrimination under the 19-year rule of President Yoweri Museveni. They say they are singled out because of the lead role that Acholis played in previous regimes’ atrocities against the Southern groups that now dominate the administration.

Indeed, many northerners — and some Western diplomats and local observers — suspect that Museveni has allowed the low-level conflict to go on in order to punish the north. The war also justifies steady increases in military spending.

“Why didn’t the government use all its clout [to stop the killing] for all those years? To isolate the north,” said Ronald Reagan Okumu, an outspoken opposition legislator from Gulu. (Born in 1969, he was named after an American screen idol whom his parents admired.)

Ugandan officials have insisted repeatedly that negotiations with the LRA are hampered by the group’s inability to set a clear agenda, a view shared by Western donors.

“Until three years ago, there was a conspiracy of silence in the international community,” a European diplomat in Kampala said. “The donors supported Museveni economically and politically, and this allowed the cancer of the north to develop.”

Things began to change after the LRA was designated as a terrorist organization by the Bush administration in late 2001. Shortly afterward, Sudan allowed Ugandan troops to cross the border to attack LRA bases. Washington gave the Ugandans some nonlethal military assistance.

But the biggest Ugandan operation, Iron Fist, which took place in March 2002, backfired. It pushed the rebels back into northern Uganda, provoking a major humanitarian crisis as villagers fled to camps. “The situation changed from a low-level local conflict into an international embarrassment for Museveni,” a Western diplomat said.

At that point, the donor community pressed Museveni to launch a genuine peace initiative. Betty Bigombe, a respected former minister then working at the World Bank, was brought in to mediate.

After several false starts, talks made progress in late 2004, but then stalled

Negotiators say there is still hope, but observers believe that the talks are dead following the defection in January of the LRA’s top negotiator, Sam Kolo, who said that Kony opposed his peace overtures. Observers warn that the government is moving back toward the military option, blaming Kony’s reported inflexibility.

“I am discouraged because I see no political solution and the military option is gaining strength,” said Anglican Bishop Nelson Onono-Oweng. “What saddens us is that this means our children will die.”

Onono-Oweng and others who have met with top LRA leaders believe that the rebels are concerned mostly with their personal fates. They say the LRA commanders are convinced the government will not guarantee their safety. The prospect of prosecution by the newly formed International Criminal Court only deepens their concerns.

Still, two Western diplomats said that the plight of the Acholis is beginning to win sympathy in the south. That has added pressure on Museveni to find a peaceful solution to a war that has cost at least $1.3 billion and that is swallowing $100 million a year, or 3% of the country’s gross domestic product, according to World Vision.

Bringing peace would also boost Museveni’s re-election prospects if, as expected, he decides to run again in March 2006. His popularity rests largely on the stability he has brought to a country bled by the dictatorships of Idi Amin and Milton Obote. Securing peace in the north would help cement it.

“There is a sense that the opportunity to conclude peace is now,” U.S. Ambassador Jimmy Kolker said. He pointed to a recent peace accord in southern Sudan as a key development, saying it would deprive the LRA of its rear base.

Some observers believe that more commitment from Washington could tilt the balance of this “winnable conflict,” in the words of Rory Anderson, World Vision’s policy director for Africa. She and other observers want the administration to dispatch a high-level envoy.

“The U.S. is not as highly motivated as it is in Sudan,” she said. “Darfur, southern Sudan and northern Uganda are all linked by the fact that those are conflicts sponsored by the Sudanese government,” she said. “So you have a trifurcated U.S. policy instead of a unified one.”

Administration officials acknowledge that northern Uganda is not a top priority, but they say they are following the talks closely. America provided $140 million to Uganda in 2004. That included more than half of all World Food Program funding and some $13 million for reintegration of child soldiers.

“This war has taken too long,” Catholic archbishop John Baptist Odama said. “It has grandchildren.”

Even if the conflict were to end and the Acholis could start to rebuild, recovery might take 50 years, said Anglican bishop Onono. “We have been falling into a pit for 19 years, and we haven’t reached the bottom,” he said. “There is no culture, no education and no morality in our community. It is a wild community, one where killing is not a problem. A dead community.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

- 4

Fast Forward What Mahmoud Khalil says about Gaza and Israel in ‘The Encampments’ documentary

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.