Sidney Eisenshtat, 90, Leading Synagogue Architect

Sidney Eisenshtat, one of America’s leading synagogue architects, died March 1 in Los Angeles. He was 90 years old.

Eisenshtat was a prolific architect in Southern California, and an influential architect of modern synagogues. He graduated from the University of Southern California ‘s School of Architecture in 1935 and maintained his architectural practice in Los Angeles for the rest of the 20th century.

Eisenshtat was an observant Jew who was past president of Congregation Beth Jacob in Beverly Hills, which he attended daily. He and his wife Alice, who predeceased him, were active participants in Jewish communal affairs.

Though Orthodox, Eisenshtat designed several noteworthy Reform and Conservative synagogues, as well as Detroit’s Orthodox B’nai David. His synagogue work is often grouped with that of his famous non-Jewish contemporaries, Frank Lloyd Wright, Minoru Yamasaki and Philip Johnson, who all designed important synagogues in the 1950s and ’60s. However, none of them professed any knowledge of or personal affinity with Judaism. For Eisenshtat, his synagogues were among his most personal creations, and in his mind they were in perfect keeping with Jewish traditions and values.

Eisenshtat established an international reputation based on the expressive design of several synagogues built between the 1950s and 1970s. He designed his first major religious structure, Temple Emanuel in Beverly Hills, in 1951, in the first flush of a national reinvention of traditional synagogue design. Eight years later, he designed Sinai Temple in Los Angeles. In the early 1960s he designed the Reform Temple Mount Sinai in El Paso, Texas, where he was commissioned to create a space that was both functional and expressive. He achieved this by integrating simple dramatic forms into a harsh but beautiful desert landscape. The El Paso synagogue and later the House of the Book, a chapel and conference hall at the Brandeis-Bardin Institute, located in Simi Valley, were integrated into striking arid landscapes, in which they are set like large sculptural works.

Influenced by the work of Eric Mendelsohn, Eisenshtat became an expert in the use of the thin shell concrete for shaping space into expressive, often soaring forms. Like Mendelsohn, he created synagogues with white walls almost devoid of decoration, but that were highly expressive through the use of simple materials and abundant natural light. He did lavish some attention on the synagogue’s focal points — especially the Ark and windows. In El Paso, he designed the Ark as a giant open-frame tripod, set within the lofty concrete-shell tent-like sanctuary. Inside is an abstract bronze cabinet for the Torah scrolls; a bronze Eternal Light hangs above it. In other synagogues he included stained glass, mosaic, and sculpture, but these were always subservient to the overall architectural design. He favored large, airy rooms, though he could create moody interiors by carefully channeling light for dramatic effect. He has been described as an expressionist and as a minimalist.

In addition to synagogues, Eisenshtat designed several centers for the study of Jewish life, including the Hillel House at his alma mater, University of Southern California. He also designed the master plan for the University of Judaism in Bel-Air (1977). Perhaps in a nod to the more secular world of Hollywood Jews, Eisenshtat designed the Friars Club in Beverly Hills (1961), frequented by many of the great Jewish comedians of the era.

The rise of post-Modernism in the 1980s and Deconstructionism in the 1990s made some of Eisenshtat’s work appear outdated, particularly among younger architects who seemed afraid of employing bold architectural gestures and large abstract forms. But the recent popularity of architects as diverse as Frank Gehry and Santiago Calatrava make much of Eisenshtat’s best work surprisingly fresh and relevant again. These “new expressionists” are more flamboyant and more indebted to technology, but they share with Eisenshtat a belief in the value of robust design.

Born in New Haven, Conn., in 1914, Eisenshtat settled in Los Angeles in 1926. He married Alice Brenner in 1937. Surviving him are his daughters Carole Oken and Abby Robyn; his sister Pauline Roberts; five grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 3

Fast Forward How Coke’s Passover recipe sparked an antisemitic conspiracy theory

- 4

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion This Nazi-era story shows why Trump won’t fix a terrifying deportation mistake

-

Opinion I operate a small Judaica business. Trump’s tariffs are going to squelch Jewish innovation.

-

Fast Forward Language apps are putting Hebrew school in teens’ back pockets. But do they work?

-

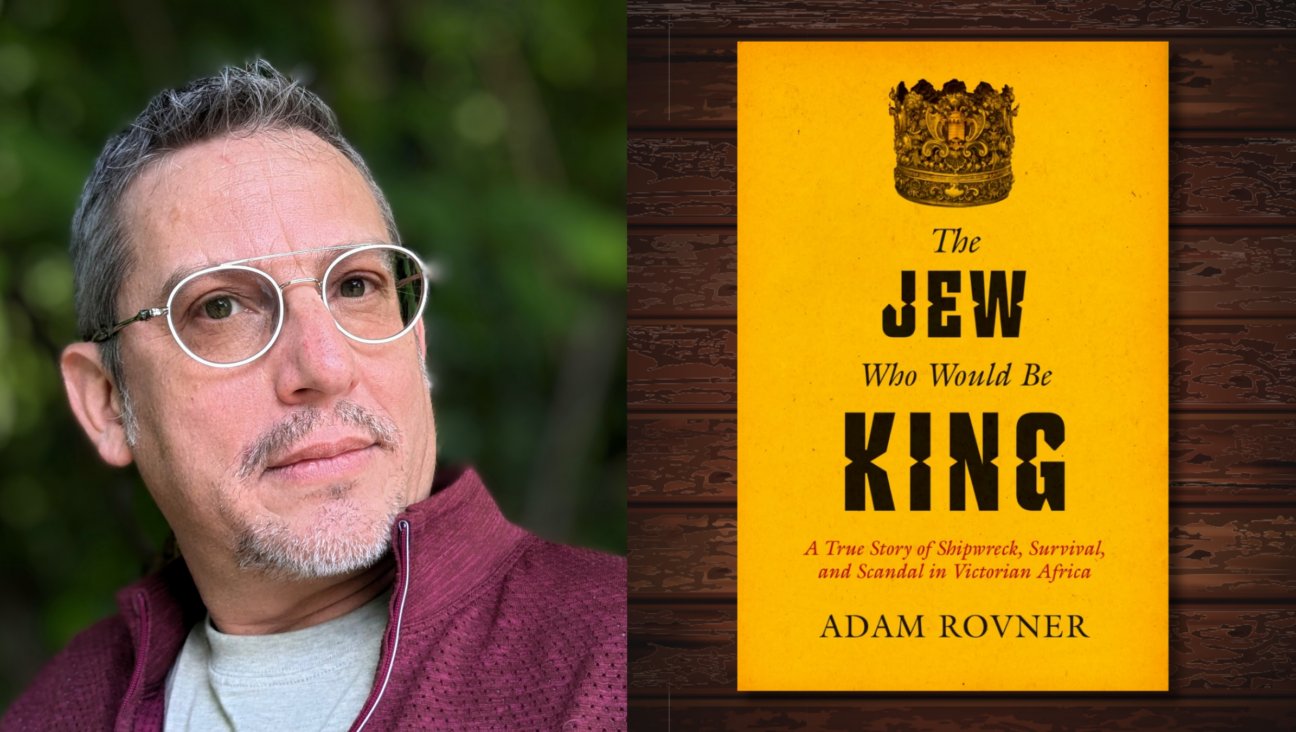

Books How a Jewish boy from Canterbury became a Zulu chieftain

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.