Tango: Not Jewish, But Not 100% Not Jewish

‘I’m not Jewish — but I’m not 100% not Jewish,” jokes innovative tango musician and sometime klezmer bassist Pablo Aslan. Much the same might be said of the tango itself.

The origins of the tango aren’t entirely clear. Some believe that the dance form, born in the slums of Buenos Aires in the 1880s, derived from an Andalusian dance of the same name. Others claim it evolved from the Cuban habañera. And some even contend it emerged from Afro-Argentine religious music.

Whatever its provenance, the tango was quickly embraced by Buenos Aires’s underclass. And according to Rabbi Arnold Kopikis, the organizer and narrator of a show titled Jewish Tango Cabaret, held this month as part of the Lipinski Family San Diego Jewish Arts Festival, that’s exactly how Jews first made its acquaintance.

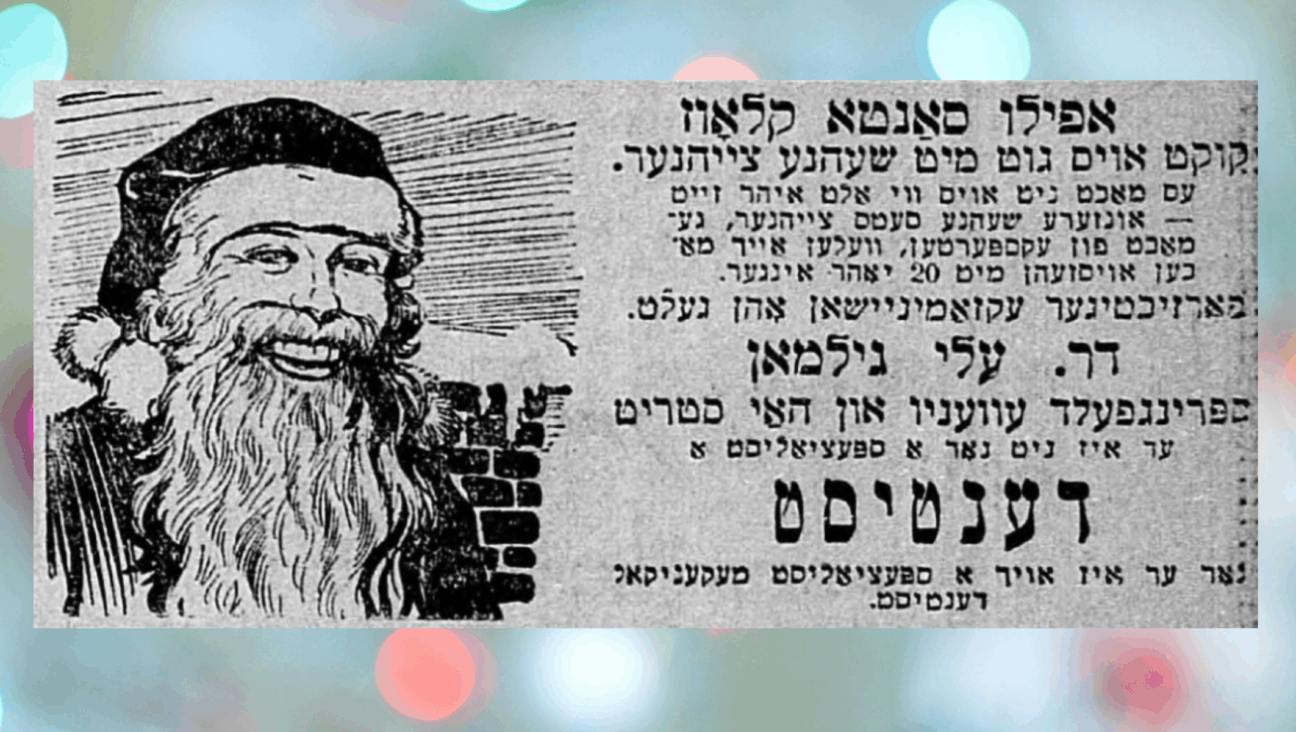

Kopikis, who was ordained at Buenos Aires’s Seminario Rabinico Latinoamericano, explained that many of the young women who first danced the tango in Buenos Aires’s bordellos were European Jews. The same network of Jewish immigrants that recruited them from the ghettos of Eastern Europe helped carry the tango to their home communities abroad.

Jews first arrived in Argentina by way of Brazil following their expulsion from Spain and Portugal. Mass immigration to the country began in the 1890s. As a result, Argentina’s modern Jewish community was born at roughly the same time as the tango itself.

According to flutist Pablo Goldstein, the show’s musical director, at first there were few Jewish tango composers and performers. But Jewish musicians — some schooled in classical music, others in klezmer — did have an impact on the art form. And Jewish music remains well known in Argentina. “You talk to any musician in Buenos Aires, and they know klezmer very well,” said Aslan.

By the 1920s, tango had entered a golden age in Argentina. Tango orchestras proliferated, and Jewish musicians and composers began to play an important role in the music. “Most of the very famous tango orchestras in Argentina had Jewish musicians,” Goldstein noted. Ironically, some were immigrants who had previously worked in European tango orchestras.

At the same time, European Jews began writing their own Yiddish tangos. Goldstein suggests that Jews in the Diaspora were drawn to the melancholy quality of the music, which echoed the sense of dislocation and rootlessness experienced by the immigrants and urban poor among whom it originated. “We Jews have had the same feeling for 2,000 years,” he said.

For European Jewry, the tango reached its apotheosis as a means of communal expression during World War II. “The Holocaust gave rise to the ghetto tango — a form of song that combined elements of tango and cabaret with disturbing lyrics that described everyday life in the ghetto, and even in the death camps,” Kopikis said. Throughout the war, Jews continued to gather in makeshift venues to hear a new art form that drew on tango, on European operetta, and on Jewish folk and liturgical music.

However, the Jewish tango did not die in the camps. In addition to presenting ghetto tangos and more traditional material by the likes of Jewish Argentinean composer Luis Rubinstein, Goldstein and his ensemble — which will be joined by Argentinean cantor Israel Ghelman and dance troupe Tango for Three — also performed several tangos from the repertoire of Israeli singer Yaffa Yarkoni. And Goldstein believes that tango and Jewish music continue to share an essentially bittersweet quality — a quality that he perceives even when playing an upbeat klezmer freilach.

“The freilach is like a costume, and the sadness is inside.”

And the tango?

“The tango is the same. But without the costume.”

Alexander Gelfand is a writer, musician and musicologist living in New York.