Under a Cloud, a Lawyer For Survivors Soldiers On

A decade after he shot to fame as a Holocaust restitution lawyer, attorney Ed Fagan now does most of his business from a cell phone. Deeply in debt, he no longer has an office and is the target of an ethics investigation that threatens to disbar him.

But this has not stopped him from continuing his old work. Last month, he went to Hungary to file a new complaint against the Hungarian and German governments, accusing them of conspiring during the 1960s to halt art restitution.

Fagan rose to prominence during the 1990s, when he was the first lawyer to file suit against Swiss banks for withholding Holocaust-era accounts. But now, the ethics investigation has turned the tables on Fagan, making him the defendant. The New Jersey Office of Attorney Ethics has accused him of “knowing misappropriation” of client money. Fagan has asked for the case to be dismissed, but a pre-hearing conference has been scheduled for June 21. Since the ethics investigation began, Fagan’s lawyer has withdrawn from the case.

Through it all, Fagan continues indefatigably filing lawsuits, hoping to find a winner.

“People can say whatever they want about who I am or what I have done,” Fagan said. “Part of what I’ve done, I’m not so proud of. What I’m most proud of is that I have never abandoned these cases.”

In his response to the Office of Attorney Ethics complaint, Fagan called himself a “sole practitioner with a very limited practice,” but Fagan’s boldness has not faded. In the pending suit against Hungary and Germany, Fagan is seeking $7 billion for the Association of Holocaust Victims for Restitution of Artwork and Masterpieces, of which Fagan is a member. Fagan claims that the two governments conspired in the 1960s to derail all future art restitution efforts. According to Fagan, the document proving this is in the possession of the Commission for Art Recovery, which is headed by cosmetics heir Ronald Lauder.

Fagan’s passion for litigation is not limited to Holocaust-related issues. In March, he filed a lawsuit on behalf of German and Austrian victims of last year’s Asian tsunami, claiming that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Thai government failed to supply adequate warning of the disaster. A month earlier, he filed a claim against the German Finance Ministry for defaulting on gold bonds issued by the Nazis — a case in which he is also listed as a plaintiff.

Fagan was one of numerous lawyers who won prominence by filing charges against the Swiss banks in the late 1990s, on behalf of Holocaust victims and their heirs attempting to claim accounts that had been dormant since World War II. Unlike most of the other lawyers who took up the cause, however, Fagan did not come from a well-established law firm or a law school faculty position. He was a personal injury lawyer who headed his own small firm. Lacking major institutional backing, he put everything on the line to pursue his powerful targets, flying around the world to find clients and hold press conferences, betting on future payments to cover costs. Now, it seems, the spending is catching up with him.

In January, the New Jersey Law Journal reported that Fagan owes some $4 million to creditors, including phone companies and real estate agents. While he began with office space in New Jersey and New York (once occupying a whole floor of the Standard Oil building), today he has no listed phone numbers. Asked about an office, he referred the Forward to a company that provides temporary office solutions, which had only an incorrect forwarding number for Fagan. Fagan says that all the current problems will go away once the awards for his current cases come in.

“With one lawsuit, the credible and legitimate creditors get paid off instantly,” Fagan said. “I can’t file for bankruptcy because my future receivables are greater than my debt.”

In the suit against Hungary and Germany, Fagan is part of a renewed push in art restitution. Last summer, a case that reached the U.S. Supreme Court opened the way for Americans to sue foreign governments for Nazi-era property in American courts. The new push has won support from American Jewish groups, but not all restitution insiders are enthusiastic about Fagan’s continuing involvement.

“Given his track record, anything he does is suspect, and you have to take a very close look at it to see if it’s serious,” opined Burt Neuborne, the New York University law professor who heads the legal team in the still-ongoing Swiss case.

Fagan won the ire of other lawyers in the restitution fight early on. Many of them accused him of being more interested in publicity than in legal details, according to several recent histories of the Holocaust restitution fights, including Michael J. Bazyler’s book, “Holocaust Justice: The Battle for Restitution in America’s Courts” (New York University Press).

Fagan and his defenders reply that his tactics got the attention of the Swiss banks and eventually led to the unprecedented $1.25 billion settlement. Another suit that Fagan helped to initiate against German companies eventually produced $5.2 billion for survivors.

“If he wouldn’t have started it all, there wouldn’t have been this avalanche,” said Hannah Lessing, secretary general of the Austrian National Fund for the Victims of National Socialism. “He is a good P.R. man. He has sold the issue well, and it has started the process in many countries of new restitution measures.”

The Swiss case, though, was not the windfall Fagan expected. While he requested $4 million for his services, the judge gave him closer to $1 million — and of that, almost half ended up going to his survivor-clients, not his creditors.

Even if the current crop of lawsuits helps Fagan pay off his debts, they won’t solve all his problems. In January the New Jersey Office of Attorney Ethics filed a complaint alleging that he took close to $470,000 out of the accounts of two clients — both Holocaust survivors – without their approval. The attorney prosecuting the case, John McGill III, said that if the charges are proved, it “will invariably result in an order of disbarment.”

In his official response to the complaint, Fagan denied the charges but said that he did not have the “information and access to records” needed to prove his case.

The first public sign of controversy came in 2000 when The New York Times and ABC News published a joint investigation alleging that while Fagan was pursuing his Holocaust-era cases he had ignored his other clients and also had been tardy in responding to many of his Holocaust survivor clients. At the time, Fagan acknowledged that he had failed to withdraw from suits he was not pursuing. “I was in over my head a lot of the time, but now I’m digging out,” he told The Times.

In the current case against Hungary, the judge chastised Fagan in a January order for “egregious failures to file timely papers and follow proper procedure.”

The Office of Attorney Ethics lodged a similar criticism in 2003, formally admonishing him for failing to “adequately communicate with a client in a personal injury matter.”

In an interview with the Forward, he said he would not comment on the ethics investigations.

Fagan had to pay one client $167,000 for malpractice in a case that began in 1993. In another malpractice suit, decided in 2004, he was ordered to pay $3.4 million to a client who had been in a car accident while wearing a defective seatbelt: Fagan had sued the wrong seatbelt manufacturer, and later on, after the case was dismissed, he did not alert his client. Fagan says he chose not to defend himself in either case because he wanted to devote his time to his current clients.

The judgments, along with the current ethics investigation, mark the latest chapter in a zigzagging career. Fagan went to law school only after considering a stint in the Orthodox rabbinate, and trying his hand at the business world. He was a personal injury lawyer with an ad on the back of the Yellow Pages when he found out that the Swiss banks still had Jewish bank accounts. Fagan was looking for a test case when Gizella Weisshaus, already a client in another matter, came to him with documentation from her grandfather’s Swiss bank accounts.

Weisshaus described herself as someone who had been a devoted client, who went so far as to volunteer in Fagan’s office and give him control of an escrow account that had belonged to her deceased cousin. She has since become one of Fagan’s harshest critics.

“He is a lowlife, what he did to me,” Weisshaus said. “I helped him. I worked for him. In the end, I became a victim.”

According to the ethics complaint, in March 1996 Fagan wrote a check for $40,000 to his own bank account from Weisshaus’s account, and only paid it back after a disciplinary hearing. To restore the funds, the complaint alleges, Fagan took money from the account of another Holocaust survivor, Estelle Sapir. In the end, the complaint says that Fagan wrongfully transferred $427,500 from Sapir’s account.

Fagan did later pay back the Sapir account with a loan from a friend, according to the ethics complaint. In his written response to the Office of Attorney Ethics, Fagan said that the ethics investigation was sparked because that friend wanted to “extort monies from me” and wrongfully gave documents to the Office of Attorney Ethics. According to Fagan, the friend was trying to involve him in a matrimonial court dispute.

As these ethics proceedings move ahead, Fagan is spending whatever time he can on the case against Hungary and Germany. He said he feels very alone. “All the other lawyers got their money and walked away,” Fagan told the Forward. “I made a promise I would continue this until the end, whenever that comes.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 3

Culture Did this Jewish literary titan have the right idea about Harry Potter and J.K. Rowling after all?

- 4

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history.

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Deborah Lipstadt says Trump’s campus antisemitism crackdown has ‘gone way too far’

-

Fast Forward 5 Jewish senators accuse Trump of using antisemitism as ‘guise’ to attack universities

-

Fast Forward Jewish Democratic Rep. Jan Schakowsky reportedly to retire after 26 years in office

-

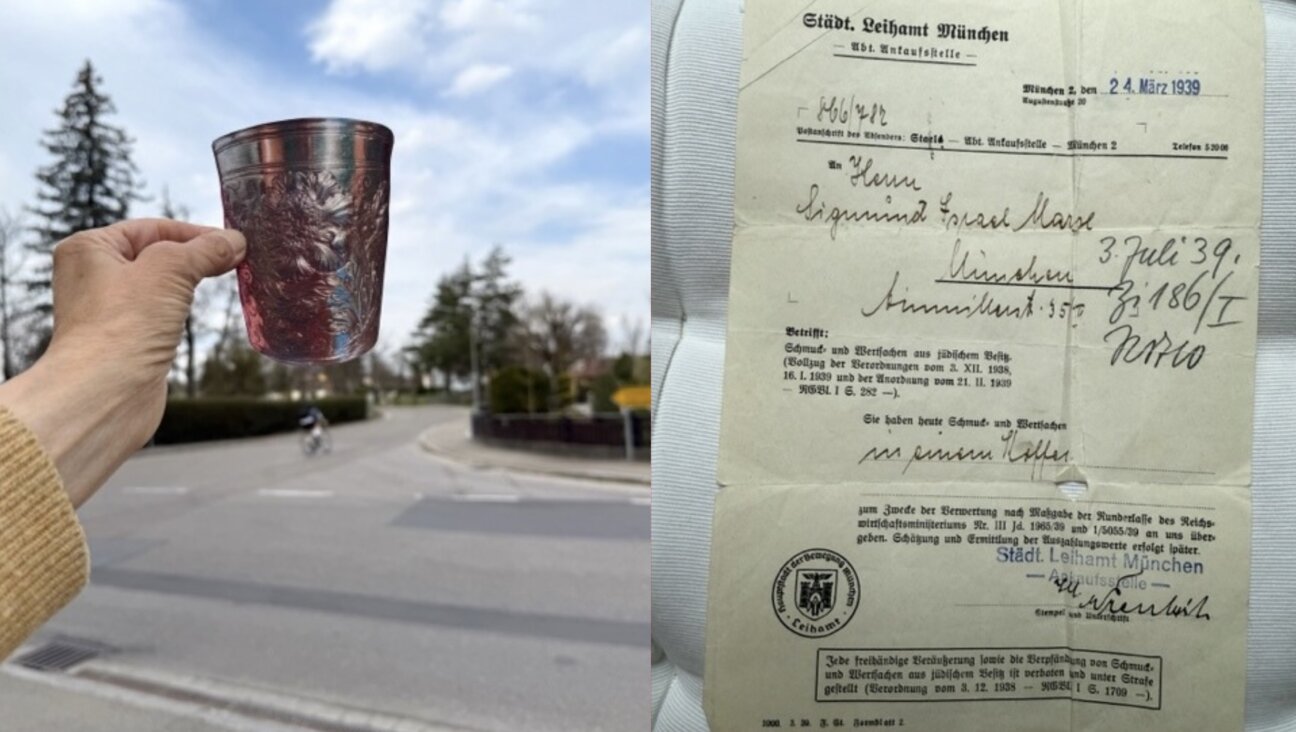

Culture In Germany, a Jewish family is reunited with a treasured family object — but also a sense of exile

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.