Holding Patterns

When sleep eludes me, I conjugate Spanish verbs. I begin with nice, regular verbs in the indicative mood. Hablar, comer, vivir: to speak, to eat, to live. I move methodically through the present tense, the preterit past, the past imperfect, the future and the conditional. Then on to forms requiring auxiliary verbs — the perfect, the pluperfect. During rare bouts of acute insomnia, I push on to the subjunctive mood: “If I were to live, if you were to live, if he/she/you (formal) were to live….” After a dozen or so contrary-to-fact statements, I lose consciousness.

My effortless knowledge of Spanish verbs attests to the staying power of, and perhaps a certain craving for, grammar. Spanish, my first foreign tongue, was also the first language I learned grammatically. I breathed in English with the pungency of my mother’s skin, but I learned Spanish from textbooks, worksheets, flashcards and colorful posters — in a classroom. Actually, in several classrooms, beginning in the third grade but becoming really serious at age 10, when I signed up for an intensive language program offering two-and-a-half hours of Spanish instruction daily.

The International Program was one of several “magnets” with which Miami’s school system hoped to draw black, white and Latino children into each other’s neighborhood schools. The two Spanish instructors were Cuban émigrés who could be maternal or mischievous, doting or disciplinarian; they got along famously and alternated playing straight man and joker. Large-hearted and enthusiastic teachers, each could be fearsome after her own fashion.

Señora Rodriguez taught us gringos; upset by some schoolroom mischief, she would mutter diffusely one or another fierce yet incomprehensible insult. When we were very good, though, she would gesture magnanimously at the jar of hard candies on her desk and invite us to “Toma un caramelo, mi amor.” From Sra. Rodriguez, I learned the whole indicative mood, various manifestations of compassion, numbers cardinal and ordinal, a few forms of grace, the rules governing accent marks, a measure of humility, and the names of animals, vegetables, fruits and household furnishings.

Señora Rosales was all sparkle and spitfire. I remember copper hair and bronze lips, blue jeans and high heels. Sra. Rosales taught the more advanced students. Her flashing smile presided over the study of European and Latin American geography, creative writing, spelling, history (especially Cuban) and science (especially fotosíntesis). But the foundation of the curriculum pursued by both Señoras was definitely grammar — administered in liberal doses and taught as it had been in Cuba: by rote. Although the caprices of memory probably have multiplied a few occurrences into many, I recall endlessly folding a sheet of unlined paper into thirds the short way, and into sixths the long way, creating a grid of 18 boxes on which to conjugate hablar, comer and vivir.

When I advanced to Sra. Rosales’s class, the grammar grew more complicated. The subjunctive mood was introduced, and irregular verbs were stressed. Much of her pedagogy involved our copying down verb conjugations from the chalkboard. Flagging under her exhaustive taxonomy of verbal irregularity, one of us young scribes might raise a tentative hand and ask, “Do we have to write this down?” Clutching her chalk, the petite Señora would spin on one heel to face us, plant the nonchalky hand authoritatively on her hip and spit out hotly, “Do you sink I’m wrrriting dis forrr my helse?”

While I don’t know how the inhalation of chalk dust and auxiliary verbs ultimately affected Sra. Rosales’s health, I can state with certainty that learning grammar — while young, and in an atmosphere of high passion — had a most salubrious effect on me. Although the exact reasons would remain nebulous for a while, a basic and life-sustaining idea came through: Grammar matters. Since my days in the International Program, I have wrangled with many grammars, only a few of which are codified in books. Along with the root systems of three Semitic languages and the case systems of two Germanic ones, I have studied less obvious grammars: the scheme of the sonnet, the conventions of friendship, the rules of relationships, and the delicate yet vital back-and-forth between a teacher and her students. In its simplest form, grammar has lulled me to sleep at night — but in its more complex forms, it has spurred me to rise each morning. The incessant drilling; the precise scoring of the page into a matrix of 18 squares; the steeping of the mind, conscious and unconscious, in the intricacies of hablar, comer, vivir: What better preparation could there have been for my later study of the most tangled and irregular language of all — the grammar of the human heart?

* * *|

“So, where are you holding?”

That question — emanating in a gruff voice from the general region of two sparkling eyes and one cocked eyebrow — always made me shudder slightly. The inquisitor was my teacher at a women’s yeshiva, where I was studying Talmud and other classical Jewish texts after college. My teacher’s phrasing of his question, entirely typical of his Yiddish-inflected English, abraded my ear like fingernails scraping a chalkboard. But I shuddered more at the content than at the diction. Before delivering his semiweekly lecture, our teacher would make the rounds of his five pairs of students polling us about our progress. My study partner and I were usually wandering among the niceties of a medieval Talmud commentary, oblivious of the gentle roar produced by 198 other women and girls reading aloud, contentiously debating definitions and interpretations. Unapologetically penetrating the fog of our concentration, the teacher would demand, “Where are you holding?” By this, he meant, “How far have you advanced on the list of assigned sources?” He meant only to gauge our progress, not to accuse us.

Yet accused I felt — for despite daily stretches of hard, steady work, I don’t recall a single week when we finished every text assigned us. The answer we gave our teacher, as idiomatically awkward as his question, was inevitably some variation on, “We’re holding in the middle.” No, we haven’t finished, but we’re plodding along as diligently as we can. After two years of study, I left Israel with sharply honed textual skills and a modest fund of classical Jewish knowledge. Yet, more resonant, more insistent than either skills or knowledge was the cadence of that twice-weekly exchange:

“Where are you holding?” “I’m holding in the middle.”

The middle is messy. My study partner, Naomi, and I sat all morning in hard plastic classroom chairs, tucked under a narrow desk topped with Formica the color of canned peas. But the desktop was hard to see while we studied. Our copies of the Talmud were propped on wooden stands; our spiral notebooks lay next to them and our hastily scrawled copy of the assignment sheet flapped off the table’s edge. Photocopies of relevant sources lay strewn about. A stack of medieval commentaries, their pages interleaved so that each book held the place in another, abutted the marble pillar in front of our desk. Half-full mugs of cocoa and, as Naomi’s pregnancy advanced, a thermos of warm milk teetered precariously at our elbows. The messy middle was dynamic: We were constantly in mental or physical motion, and sometimes both. After several minutes of quiet thinking, one of us would slap both palms against the desk, or chuck the other on the shoulder blade, thrilled with some painstakingly won realization. When it was time for class, all the extraneous books were returned to their shelves, the papers filed in notebooks, the wooden bookstands folded neatly, the cocoa gulped hastily and the mugs rinsed. Our pea-green desktop came back into view just in time for us to leave it and head to the classroom upstairs.

* * *|

Two years after leaving the yeshiva, I began to study Yiddish. Suddenly I understood phrases and mannerisms I’d witnessed, unthinkingly, my whole life. I learned why, upon taking leave of someone, Jews say, “Be well” instead of “Take care” (pure Yiddish); why my mother so often intoned, “From your lips to God’s ear” (a snippet of national anthropomorphism, not her own heterodoxy). I espied the mashed skullcaps of Yiddish nouns and verbs peeking out from under their Americanized baseball caps. I certainly gained insight into the vocabulary of my Talmud teacher. I came to recognize the question “Where are you holding?” as the literal translation of an idiom using the verb haltn. Like its English cousin “to hold,” the word haltn has a wide semantic range: to contain; keep; believe, think, be of the opinion; affirm; observe a holiday; live up to promises or principles. Combined with a preposition, more nuances emerge: to agree or approve; to be in the midst of or about to do something; to trust.

The word’s agility instinctively made sense to me since “holding” has had a wide range of meanings in my life, too. The idea of holding has dominated the most important conversations I conduct with myself. If not with my Talmud teacher’s semiweekly regularity, then with redoubled urgency, I ask myself not only, “Where am I holding?” but also, how, what, and why am I holding. Answering these questions has meant nothing less than forming an identity, growing into an adult with particular commitments, passions, aversions and dreams. Every worthwhile way of living, I have noticed, involves holding: holding up, holding on, holding in, holding out.

Holding is also what a grammar does. Grammar takes disparate nouns and verbs — parts of speech and parts of experience — and holds them together so that meaning emerges. An introductory college linguistics class stressed the idea that grammar is conventional. Speech patterns are “correct” insofar as a society recognizes them as meaningful. I have come to understand what the Señoras accomplished with their endless conjugation matrices: They taught us to communicate so that we could understand and be understood, to speak and write in ways that would bind us to other people in meaning and in love. Itself arbitrary, grammar can stand for all kinds of rules and patterns from which meaning is made. I see grammar as a holding pattern: not in the aerial sense of going round and round in circles so as to hold still, but rather as the fixed, immovable thing from which movement and freedom are born. The right sort of bondage (and there is no one “right” sort) will set us free: to speak, to eat and to live as passionately and profoundly as we can.

Miriam Udel-Lambert, a doctoral candidate in comparative literature at Harvard University, has taught in the Jewish communities of New York and Boston. She is at work on a book about forming an adult religious and intellectual identity.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 3

Culture Did this Jewish literary titan have the right idea about Harry Potter and J.K. Rowling after all?

- 4

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history.

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Deborah Lipstadt says Trump’s campus antisemitism crackdown has ‘gone way too far’

-

Fast Forward 5 Jewish senators accuse Trump of using antisemitism as ‘guise’ to attack universities

-

Fast Forward Jewish Democratic Rep. Jan Schakowsky reportedly to retire after 26 years in office

-

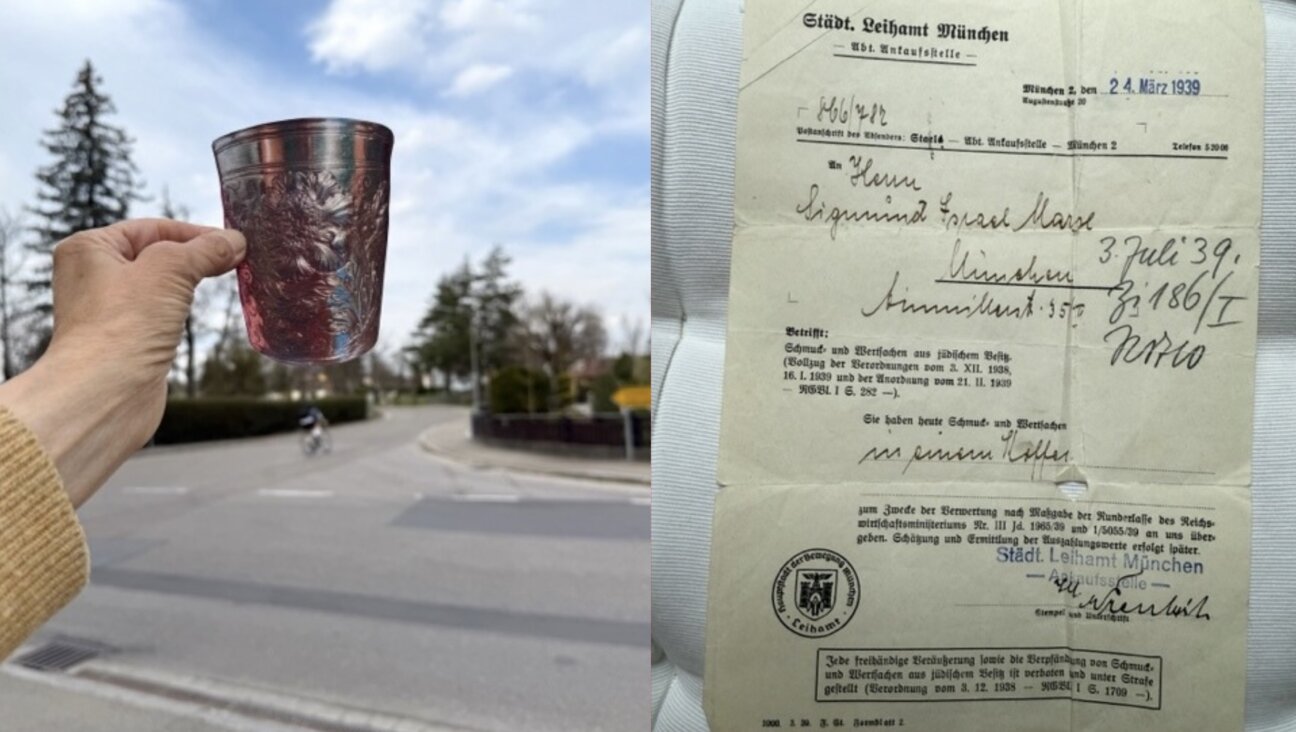

Culture In Germany, a Jewish family is reunited with a treasured family object — but also a sense of exile

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.