Filmmaker Confronts ‘Protocols’ Myth in Documentary

In the weeks and months after the attacks of September 11, 2001, filmmaker Marc Levin kept hearing from New York City cab drivers that no Jews had died in the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. One Egyptian driver not only repeated the canard that “Jews were warned about 9/11,” but posited that the alleged heads-up was consistent with “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” the notorious fictional 19th-century account of a meeting held by Jews to plot world domination.

“I just kind of flipped out,” Levin said, recalling his reaction. “I said, ‘My great-grandfather was at that meeting.’ The cabbie didn’t know what to make of that exactly.”

Then Levin heard that an Arab American newspaper in Patterson, N.J., had started serializing “Protocols.” That did it. He became determined to use his craft to document the re-emergence of “Protocols” and antisemitism in the wake of 9/11.

Two years later, he finished “The Protocols of Zion,” which will have its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah on January 21. In the 90-minute film, Levin, one of the nation’s most respected documentary filmmakers, personally confronts antisemites of various stripes. Levin predicts the documentary will “stir it up” at Sundance, where he expects to negotiate a distribution deal for a theatrical run that could begin as early as this spring or summer. HBO already has bought North American television rights to the film and will run it in 2006. Levin also anticipates a sale of European TV rights.

“Marc couldn’t read the newspapers and see the potential for antisemitism at the level it is at without doing something,” said Mark Benjamin, who served as director of photography on “Protocols” and has worked with Levin on some 25 documentaries and feature films. “He had to make this film.”

Levin’s great-grandfather obviously wasn’t part of the fictional Elders of Zion confab, but he was responsible for the Levin family’s first foray into the motion picture business. Isaac Levin purchased a couple of movie theaters in New York in the early 1900s, one of which still generates income for the family. A couple of generations later, Isaac’s grandson, Al — Marc’s father — became a TV producer. Marc joined his father on Bill Moyers’s production team during the early days of public television. Today, a third generation of Levin is poised to enter the film biz: Marc Levin’s son, Daniel, is studying film in college, where he recently made a black comedy about assault weapons.

The family also has quite a history in both organized religion and organized labor. Marc Levin’s grandfather, Herman Levin of Brooklyn, helped the late Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan found the Jewish Reconstructionist movement in the 1930s after growing displeased with the role of women in his Conservative synagogue. (The record should note that Levin’s synagogue, the East Midwood Jewish Center, now bills itself as an egalitarian congregation.)

Levin’s parents were labor organizers before becoming white-collar professionals. Prior to her career as a psychologist and college professor, his mother, Hannah, was a shop steward for the old International Union of Electrical Workers. And Levin’s father worked for the International Association of Machinists, organizing New Jersey railroad workers. Al Levin went on to a job as a rewrite man at Dorothy Schiff’s old New York Post. He served as one of Bill Moyers’s producers for many years.

“I stand in awe of how much further Marc has gone on his own,” said Al Levin, the 79-year-old family patriarch, who lives in a house in Maplewood, N.J., “decorated” by two graffiti artist grandsons. “Marc is at a level of producing that far surpasses what I was able to accomplish.”

Marc Levin’s success in both the documentary and feature film world is unusual. Among other awards, he won a national Emmy in 1988 for a Bill Moyers special on the Iran-Contra affair, “The Secret Government.” He made the feature film “Slam” after working on a documentary about a Washington, D.C., jail. “Slam” told the story of a fictional African-American performance poet imprisoned for a minor drug offense, winning a Grand Jury Prize at Sundance and the Camera d’Or at Cannes in 1998.

A couple of Levin’s features received what kindly could be called lukewarm critical response. His first feature, “Blowback,” was about a fanatical CIA agent.

“It was somewhat of a lunatic endeavor,” Levin said with a chuckle during a walk through his sprawling production office on the far west side of Manhattan.

Levin also made “Brooklyn Babylon,” which was released in 2000. Its storyline included an improbable romance between a Hasidic woman and a Rastafarian rapper in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights.

Initially, Levin was inclined to lampoon the Protocols by dramatizing it with a cast of “Jewish elders” to include Mel Brooks, Rob Reiner and Woody Allen. But apparently both the Hezbollah satellite TV network and Egyptian television beat him to the punch by releasing their own models of just such dramatizations in two different programs.

Levin came to the conclusion that the best way to approach the topic was in documentary form, but he knew he wouldn’t make an academic, PBS-style historical documentary.

“I decided I was just going to get out there and mix it up with the people who were buying and proselytizing [with] this stuff,” he explains.

What emerged is a documentary in which Levin confronts Arab Americans, black nationalists, Christian evangelicals, skinheads and a street vendor selling the Protocols on the perimeter of a demonstration against the war in Iraq. It is the first time in his career that Levin wanders in front of the camera.

“Marc stands nose to nose with these guys and says it’s a big lie,” said Benjamin, who, like Levin, is a critic of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank but is also concerned about the potential for “explosive antisemitism” in Europe and the United States.

But Levin insists his “Protocols” film is about something larger than antisemitism.

“In the end, it’s about a journey to the heart of hate,” Levin told the Forward. “It’s about how you deal with people who hate not just Jews, but Americans, Christians, whoever. And they’re willing to blow themselves up. They’re willing to blow up the whole world.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Chicago man charged with hate crime for attack of two Jewish DePaul students

-

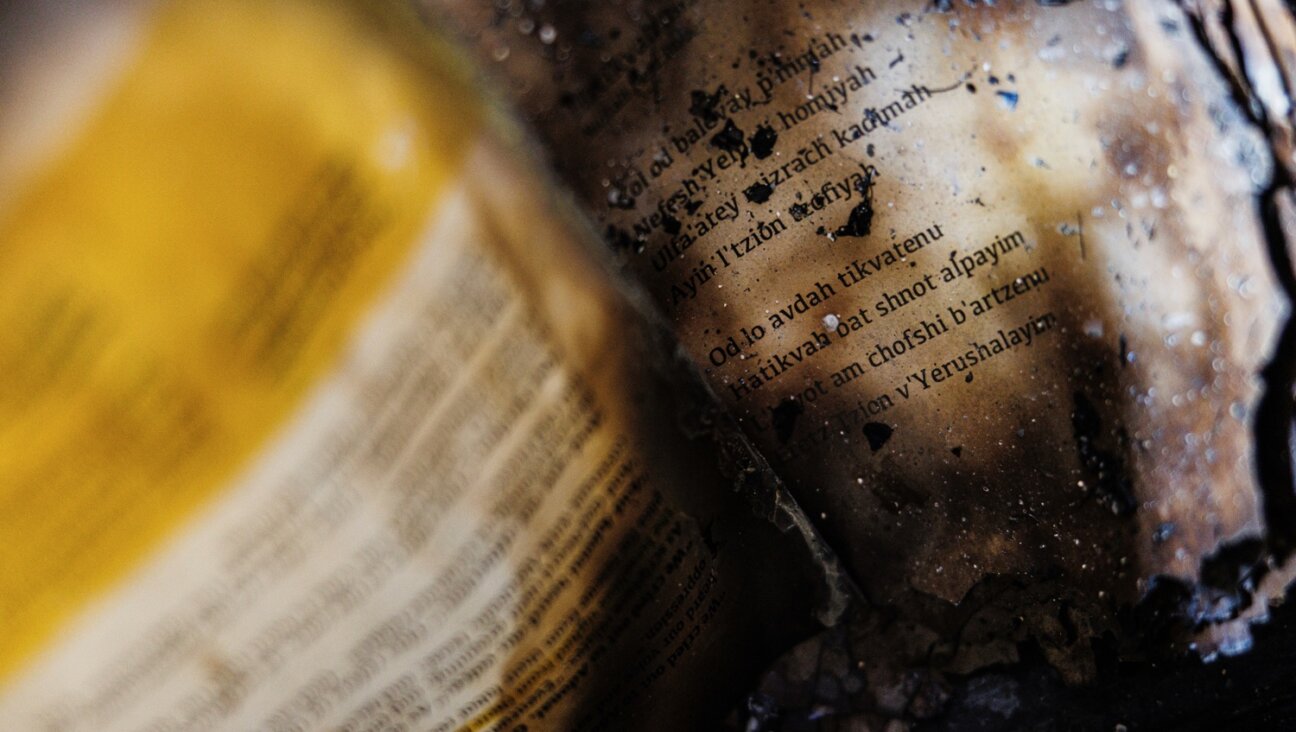

Fast Forward In the ashes of the governor’s mansion, clues to a mystery about Josh Shapiro’s Passover Seder

-

Fast Forward Itamar Ben-Gvir is coming to America, with stops at Yale and in New York City already set

-

Fast Forward Texas Jews split as lawmakers sign off on $1B private school voucher program

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.