Kippah Couture

My sister, Wanda, and her boyfriend, Michael, were driving our family car in New York City when Michael came across two pieces of round fabric in the console between the two front seats. He held them up to his chest and asked my sister, “How does Angela wear these?”

Neither Wanda nor Michael is Jewish, but Wanda recognized the circular, suede items as yarmulkes and set him straight with respect to my undergarments. I hadn’t realized that yarmulkes, which will be very much on public display with the Days of Awe upon us, were so easily confused with pasties.

As a former Christian who converted to Judaism, it took me several years to understand why men wear yarmulkes, why they choose the specific ones that they choose and why on Yom Kippur the suede yarmulkes are traded in for big white ones. Derived from the Aramaic yira malka, the English word yarmulke translates as “awe of the king” and reminds one to be mindful and in awe of God’s presence. In biblical times, only the high priest was required to don a head covering — kippah, or dome, in Hebrew — when performing his duties in the Temple in Jerusalem. Historically, Jews have both worn and not worn yarmulkes, hats, turbans or other head coverings, depending on the country they inhabited, how much antisemitism they encountered and the severity of their hair loss. Now, while some men wear them every day, others will toss one on when they eat, pray, study sacred texts or attend synagogue — or, as in my husband’s case, when his mother comes to visit.

What remains puzzling to me is that on the morning of Yom Kippur, my husband and sons never can seem to find the perfect yarmulke, the one that is far superior to all others, the one that requires a massive search and entails spilling out drawers and closets when it turns up missing. This, despite the plethora of rebellious yarmulkes that run amuck in our home: I have spied them atop a sculpture in the living room, on the bedside dresser, mixed in with toys, in a bag of mismatched socks and gloves, in various drawers, on the bathroom sink, and in a 9 inch x 12 inch plastic container dedicated solely to the storage of yarmulkes picked up by my klepto-kippah-maniac husband and sons. I recently complained to a friend that my yarmulkes were out of control and asked her what she thought I should do. Donate them to lactating friends? Use them as drinks’ coasters? After smugly boasting that she keeps her family’s collection on a short leash, she pointed out that with “Bar Mitzvah of David” and “Wedding of Naomi and Harold” engraved on the inside, these disparate purple, blue, light-green and orange yarmulkes serve as a scrapbook, a chronological tapestry of life-cycle events. It is especially fun, she said, when you find your family in another family’s yarmulke drawer.

My husband favors gray- or black-suede yarmulkes but reluctantly must forgo donning them on Yom Kippur, when wearing leather is forbidden. We suspect that he matches them to his suit, fearful of making the dreaded yarmulke faux pas. My older son’s childhood passions were mirrored by his yarmulkes, which were painted with Barney, Elmo, Batman, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and baseball and soccer motifs. Today, he is more willing to take fashion risks and might sport a navy- or a brown-suede yarmulke. For my youngest son, ease and comfort are the most important criteria, so he chooses big white or black cotton yarmulkes that stay on his head without the need for a clip.

Some men are steadfast and loyal to one yarmulke, and one only. My friend Rachel’s husband, Yossi, has worn the same bluish, knitted yarmulke with the Jerusalem skyline etched around the bottom for the past 25 years. He wore it on his wedding day, and when it went missing for three months it was dark and gloomy times in their home. Then one Saturday, over lunch at Rachel’s sister’s house, lo, the yarmulke showed up on her 1-year-old nephew’s head! Apparently, Yossi had dropped it during a previous Sabbath meal and someone had unknowingly picked it up afterward and stuck it in the yarmulke drawer. It was a joyful reunion, once the pot found its top. Many consciously choose the type of yarmulke to wear, and with the same degree of seriousness with which Isaac Mizrahi selects the perfect black T-shirt. They may seem interchangeable to the uninitiated, but for those in the know, kippah couture offers a lot of information about the wearer.

“Head coverings serve practical functions and can convey aesthetic choices, but they also can index both individual and group identity,” said folklorist Ilana Harlow, senior folk-life specialist at the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center, in an e-mail interview with the Forward. “Often they are a sign of membership in a group, or of status within that group.”

So, for example, a hatlike, brightly woven Bukharan yarmulke very probably indicates a hippie-ish, liberal-leaning Jew — unless it’s worn by a woman, in which case she might be a Reform rabbi or a feminist/observant Jew. The black-velvet or suede ones send a different smoke signal to those within the tribe. The Hasidic and ultra-Orthodox men who populate Manhattan’s diamond district, and who reside in the Boro Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, reach for the large, black-velvet yarmulkes, while Modern Orthodox men, loosely defined as those who are religiously observant but are also avid fans of “The Sopranos” and attend Yankees games, will wear knitted ones. A good friend of mine advised her daughter in Israel: “Don’t date anyone who doesn’t wear a kippah. He’s only in it for the raw sex. Find someone who wears a knitted kippah.” For her, a knitted yarmulke connotes someone who is traditional with good values, but open-minded and not fanatical. In Israel, one’s yarmulke reflects not a person’s level of religiosity but also where he or she stands politically, with the larger, knitted ones indicating a more rightwing bent.

This expectation that one’s yarmulke reflects something about the wearer — his spirituality, his creativity, his masculinity, his political stance, which sports team he identifies with — is a recent phenomenon. In the past, the message that wearing a yarmulke sent was simply that you were an observant Jew. In the past 10 or so years here in New York City, there has been a marked upsurge in the number of Modern Orthodox, kippah-clad men displaying their Jewishness out loud and proud. According to social psychologist and writer Bethamie Horowitz, who shared her thoughts in an e-mail interview, this trend began taking hold in the late 1960s and ’70s as a result of both a more dense Jewish population in the city and the “post-1967 upsurge in Jewish pride in the aftermath of the Six Day War, and the spiritual seeking characterized by the Jewish counterculture of that time.” During that same period, Horowitz recalls summer camps in which teenage girls “lovingly — and sometimes obsessively/possessively — crocheted kippot for their boyfriends. The ultimate signal of affection.”

Now, a person’s yarmulke can say pretty much anything he or she want it to say, as in the case of an elderly man on whose yarmulke is written, “My grandkids are cuter than yours.”

Ultimately, the message that the yarmulke sends was not originally meant for the world at large, despite being clearly visible to all. It was, and remains, not a fashion statement but a message to God, and a message to oneself, to be mindful of God’s presence in one’s life. It is a reminder to behave in a manner imbued with yira malka, awe of the king.

Angela Himsel’s writing has been published in The New York Times and in Jewish Week, online at beliefnet.com and elsewhere.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 3

Fast Forward How Coke’s Passover recipe sparked an antisemitic conspiracy theory

- 4

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion This Nazi-era story shows why Trump won’t fix a terrifying deportation mistake

-

Opinion I operate a small Judaica business. Trump’s tariffs are going to squelch Jewish innovation.

-

Fast Forward Language apps are putting Hebrew school in teens’ back pockets. But do they work?

-

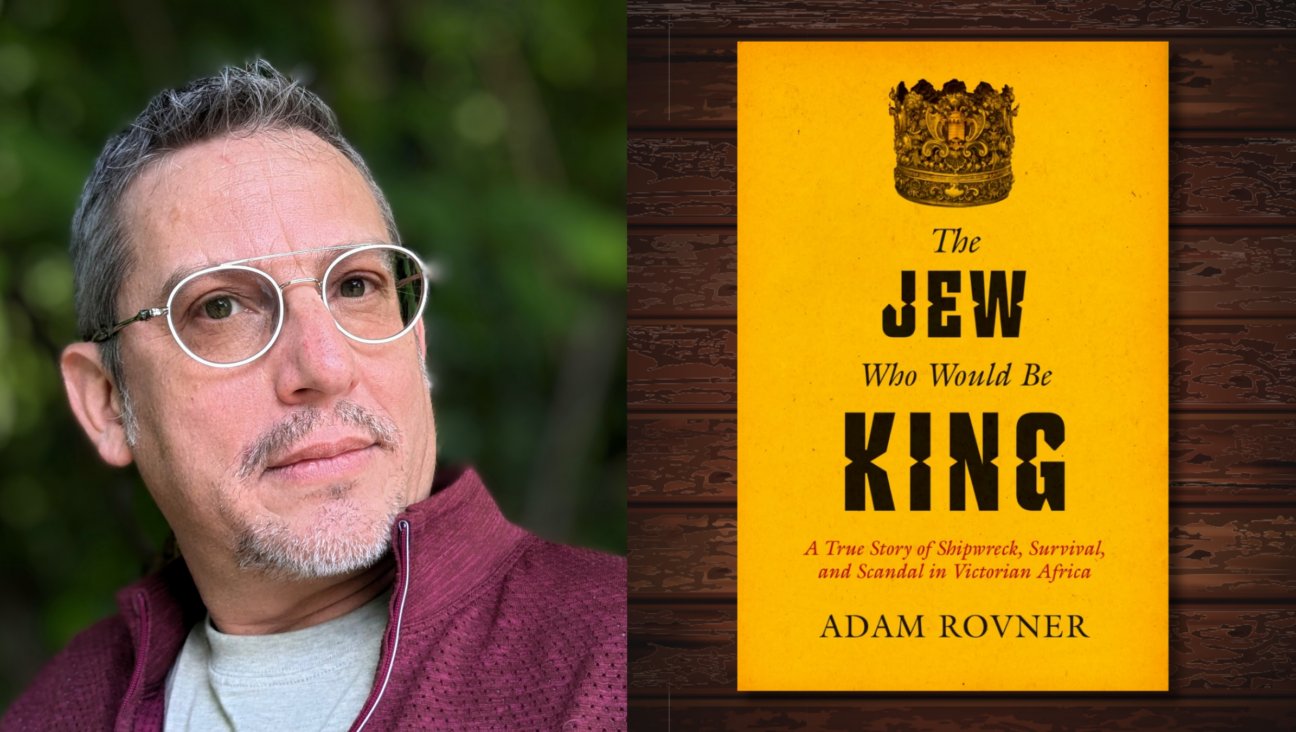

Books How a Jewish boy from Canterbury became a Zulu chieftain

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.