Back to Bauhaus

To many tourists, Tel Aviv is merely an obligatory pit stop with an airport and a sunny beach, so they quickly move on to venerable Jerusalem for a dose of sightseeing and history. Having sprung up on the sand dunes mere decades ago, little in the newborn metropolis was considered worth preserving.

But now that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization has designated the “White City” of Tel Aviv as one of 24 new World Heritage Sites, the world can appreciate that underneath these sullied facades is a premier collection of International Style architecture. What makes this Unesco recognition of “outstanding universal value” unique is that of the 754 sites, only one other modern city, Brasilia, is a 20th-century phenomenon.

Walter Gropius, who believed in the dictum of “less is more,” established the Bauhaus School in 1919 in the Weimer Republic. Simple and pragmatic, ornamentation was derived from the shapes and rhythms of the buildings’ structural elements and the play of light. Typical Bauhaus touches are narrow, horizontal “ribbon” windows and balcony openings, frequently broken by a vertical stairwell window extending from the ground floor to a cupola above the roof.

From 1919 until the Nazis’ rise to power, 19 students from Israel studied in the Bauhaus School, among them Arieh Sharon, Shmuel Mestiechkin and Munio Gitai-Weinraub. They exerted a vital influence on Israel’s architectural style. Bauhaus developed simultaneously in Jerusalem and Haifa, but it was in Tel Aviv, unencumbered by history and extant buildings, that Bauhaus flourished and came to exemplify the socialists’ ideals of the new state. It eventually became the world’s first city comprising almost exclusively white cubist buildings, prompting poet Nathan Alterman to declare it the “White City.”

To accommodate Israel’s climatic and economic conditions, the Bauhaus design underwent several unique adaptations: Buildings were constructed of cement and plaster; the heat demanded smaller openings and overhanging “brows” to obstruct direct rays; flat roofs became garden terraces; and pilotis, or pillars, supporting the first floor created an expansive garden space and allowed sea breezes to penetrate further into the city. After World War II brought a flood of new immigrants in search of housing, shoddy Bauhaus facsimiles proliferated. Meanwhile, balcony enclosures, unsightly shutters, and additions on the roofs and between the pilotis obscured the elegant Bauhaus lines. By the late 1960s, Tel Aviv was a city distinguished by its uniform unattractiveness.

Now, with almost 4,000 buildings in central Tel Aviv considered treasures, the municipality has granted subsidies for renovations and hundreds of private and public buildings have been restored to emphasize the simple contours that exemplified their utilitarian style. Among the fine examples of restoration is the former Esther Cinema in Dizengoff Square, now refurbished as the intimate Hotel Cinema, wrapped in curving balconies and featuring a swooping interior staircase.

The restoration efforts were largely due to the work of the indefatigable Nitza Szmuk, director of the Modern Heritage Conservation and Management. “My work was extremely frustrating because there was only one other part-time person to help, and there was little government funding,” recalled Szmuk. “On bad days I’d think it was useless to continue. But every month I’d see one more building restored, and it gave me courage to continue.”

Marking the celebratory week of June 6-12 was a conference on “Critical Modernists: A Tribute to Tel Aviv”; the unveiling of a series of sidewalk markers highlighting select buildings, and an exhibit at the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion of Contemporary Art called “To Live on the Sands,” which continues until August 7. Curated by Szmuk, the exhibit features photos, maps, three-dimensional models and historical films. One exhibit is devoted to the evolution of the Tel Aviv balcony, one of the most prominent local expressions of the International Style.

For those interested in taking a walking tour, drop in at the Tel Aviv Bauhaus Center at 155 Dizengoff St., owned by Micha and Shlomit Gross. Their love affair with Tel Aviv’s architecture prompted them to open the shop in 1999 on Ben Yehuda Street, eventually moving to their expanded space at Dizengoff, which sells books, art and gifts and has a gallery of exhibitions on architecture.

Bill Strubbe is a freelancer who has visited Israel 20 times. Though initially appalled by Tel Aviv’s uniform ugliness, he slowly has grown to love the architecture.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

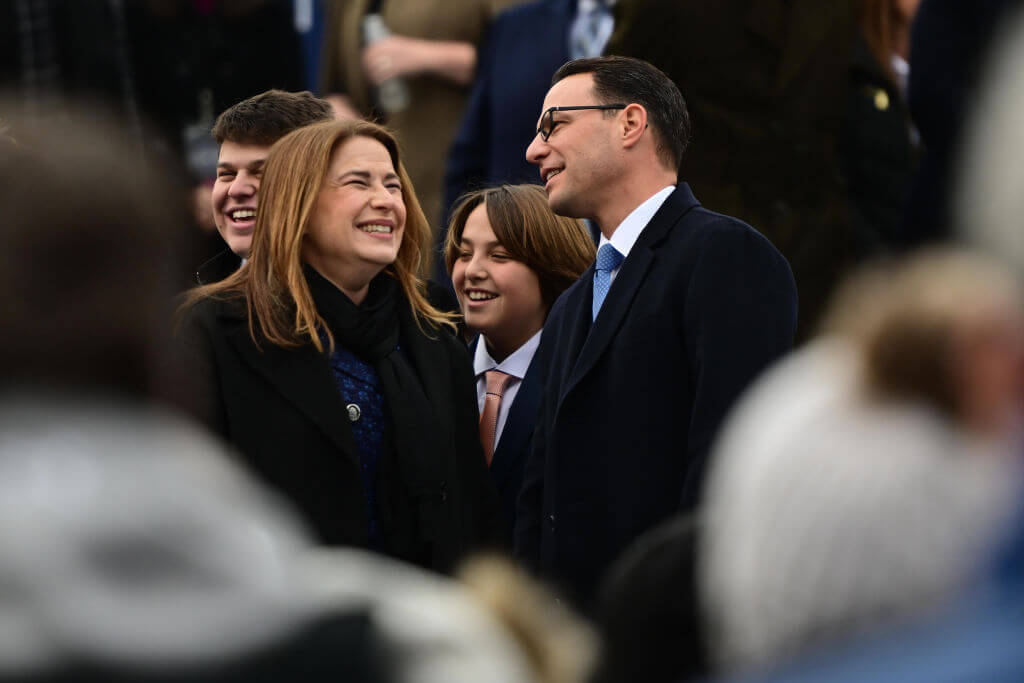

Politics Meet America’s potential first Jewish second family: Josh Shapiro, Lori, and their 4 kids

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Who killed Jesus? It wasn’t the Jews, writes a scholar of Roman law.

-

Fast Forward Is ‘New Absolute Bagel’ real? A sign stirs fretful optimism on the Upper West Side.

-

Opinion Yes, the attack on Gov. Shapiro was antisemitic. Here’s what the left should learn from it

-

News ‘Whose seat is now empty’: Remembering Hersh Goldberg-Polin at his family’s Passover retreat

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.