Russian Immigrants Struggle in Small German Towns

HAMELN, Germany — Sounds of hammering and sawing came from the back of the six-year-old Jewish community center in this Lower Saxony town. Three older men, all volunteers, were at work on a stage for the new prayer room.

Surrounded by sawdust and pine planks, the men took a break to debate, in Russian, the proper way to affix a mezuza to the door frame. After about 20 minutes of discussion the men admitted that none had ever seen a mezuza on a door before, and they decided to wait on any decision until the next of the infrequent visits to their town by a rabbi.

The energy and commitment of these men gives reason for the high hopes that have been pinned to Germany’s burgeoning Jewish community — the fastest-growing Jewish community in the world, thanks to the steady flow of immigrants from the former Soviet Union. But hopeful discussions about a Jewish renaissance in Germany often overlook the difficulties many of these new immigrants have had both integrating into German society and reconnecting with a Jewish faith that was lost to them in the atheistic Soviet Union.

“We can’t say now that Judaism is seeing a rebirth,” said Paul Harris, an expert on Russian Jewish immigrants at Georgia’s Augusta State University. “It’s far from being there.”

Since 1991, when Germany opened its borders to Jews from the former Soviet Union, more than 170,000 Jewish immigrants have arrived. Last year, for the first time ever, more Jews fleeing the ravaged economies of the former Soviet Union came to Germany than either Israel or the United States.

As part of the policy of accepting Jewish immigrants, which is seen in Germany as an act of repentance for the Holocaust, each new family is assigned to one of Germany’s 16 states by a strict formula. As a result, Jewish communities have sprung up almost overnight in cities and towns such as Hameln, population 59,000, that had no Jewish community before.

The distribution program was designed to spread the financial burden of the immigrants among the German states as well as to avoid creating Jewish ghettos in the large cities such as Berlin and Frankfurt, toward which immigrants would otherwise be drawn.

But in cities and towns such as Hameln, with its 450 Russian Jewish immigrants, the effort to disperse immigrant settlement has created isolated pockets of immigrants with few social or religious resources at their disposal.

A majority of the Jewish immigrants are living in places that until recently did not have Jewish communities, experts say. A full 72 of the 85 Jewish congregations officially recognized by the Central Council of German Jews were founded since 1991. Most are composed exclusively of immigrants in areas with no previously established Jewish community.

One of the three volunteers working on the community center’s prayer room, 65-year-old Vilen Kogan arrived in Germany six years ago and spends all his days at the synagogue speaking Russian. Discussing his work at the synagogue in broken German, Kogan, who has a cross tattooed on his bicep, makes no mention of any particular devotion to Judaism. Unemployed, he simply has nowhere else to go during the day.

Kogan’s 28-year-old son, Boris, came to Germany at the same time as his father. He spends all his time with the other young Russians in town. Like his father, he has not found steady work since arriving in Germany, with its rigid labor market.

In Israel and America, where Russian immigrants have been settled in places with already established Jewish communities, the unemployment rates for the newcomers have dropped close to that of the larger population after three years. In Germany, the unemployment rate for Russian Jewish immigrants has remained at 40%, and it is even higher in small and midsized cities such as Hameln.

But Boris Kogan is not resigned to volunteering his time at the synagogue. While his father helps build the prayer room, he and a friend are across town setting up a beer garden they plan to open during the fall.

This leaves him little time for Jewish activities. He has never been to the community center and said, “Only the old people have time for that.”

“I know I am Jewish — it said so on my passport in the Ukraine — but it is not important to me,” Boris said.

This is a typical attitude among younger and middle-aged immigrants, said Olaf Gloeckner, who researches Russian Jewish immigrants at the Moses Mendelssohn Center in Potsdam, Germany.

“Among the middle generations coming to Germany, there has been almost no inclination to turn to Jewish religion,” Gloeckner said.

The energetic leader of the Hameln community, Jakov Bondar, recognizes the lack of engagement among the younger immigrants with exasperation.

“It’s so important for us to have Judaism here. It’s what sets us apart,” Bondar said. “I’m glad that I was discriminated against in Russia for being a Jew. Otherwise I would have forgotten I was Jewish.”

But without any established Jewish community nearby, he has struggled to transmit his enthusiasm for Judaism to the younger generation. He has set up a Sunday school to get the youngest generation involved, but he has not found anyone who knows Hebrew, and as a result, the lessons consist mostly of efforts to transmit the Russian language, along with a few biblical stories from a Russian book of Jewish tales.

A rabbi — there are only 34 in Germany, according to the Central Council — visits the congregation every few months, and emissaries from the chasidic Chabad outreach organization make occasional stops, but for the most part, the congregation’s Russian immigrants are on their own when it comes to building a Jewish community.

Consequently, the congregation is not particularly observant. A yarmulke is not required in the prayer room, and breakfast with Bondar and Kogan is fried shrimp. Nevertheless, when Bondar is asked the denomination of his congregation, he quickly answers: “Orthodox.”

The answer is less a statement of doctrinal belief than a response to the complex religious politics of Germany.

The Central Council for German Jews, which oversees the government funding for local congregations, has frequently voiced its preference for congregations that observe matrilineal descent and its reluctance to fund Reform Judaism, which was founded in Germany.

Soon after Bondar founded his congregation, an American-German Jew set up a Reform congregation for Russian immigrants in Hameln with support from the Appleseed Foundation, an American philanthropy. In order to differentiate his congregation, and retain the support of the Central Council, Bondar is forthright in declaring his commitment to traditional Judaism.

While Bondar’s congregation is funded by the Central Council, he complains that even the approximately $30,000 it receives each year is not enough to purchase the prayer books and kosher food needed to establish a functioning congregation.

The Central Council’s executive director, Stephan Kramer, said that he commiserates with Bondar.

“The financial support for the existing communities is by far not enough for the quick establishment of the necessary infrastructure for the still-growing economic, social and religious demands of the communities and their members,” Kramer said.

But Bondar insists that the larger problem is that Russian immigrants have little pull in Central Council debates over questions such as where the available money goes and how quickly it flows to the Russian communities.

While new immigrants make up 70% of the registered Jews in Germany, they are not represented on the executive board of the Central Council, and only two of the 16 chairmen of the individual Jewish state federations are Russian immigrants.

Without a grasp of the German language and removed from the established urban centers of Jewish power in Berlin and Frankfurt, the immigrants have struggled to get a foothold in the Jewish establishment.

The distance between the new and old communities has been accentuated by a skepticism toward the new immigrants among the existing Jewish community.

“The Jews who were in Germany were already very concerned with being accepted,” said Andrei Markovits, a professor of German politics at the University of Michigan, “and then in come these new guys from the East — the Ostjueden — who the Western Jews have always looked down on, long before World War II.”

Bondar said that this attitude comes across very clearly. When he has asked for more help from the existing Jewish community, he said he frequently receives the same answer: “You Russians come and expect everything. Have patience. We were patient when we returned after the war.”

But Bondar warns that without more resources to build a Jewish community in Hameln, the younger generation will be lost to Judaism.

“We have no teacher for Hebrew and no rabbi,” Bondar said. “Slowly the congregation will turn into a hobby club or a social help center. Instead of integration, this is the way to assimilation.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

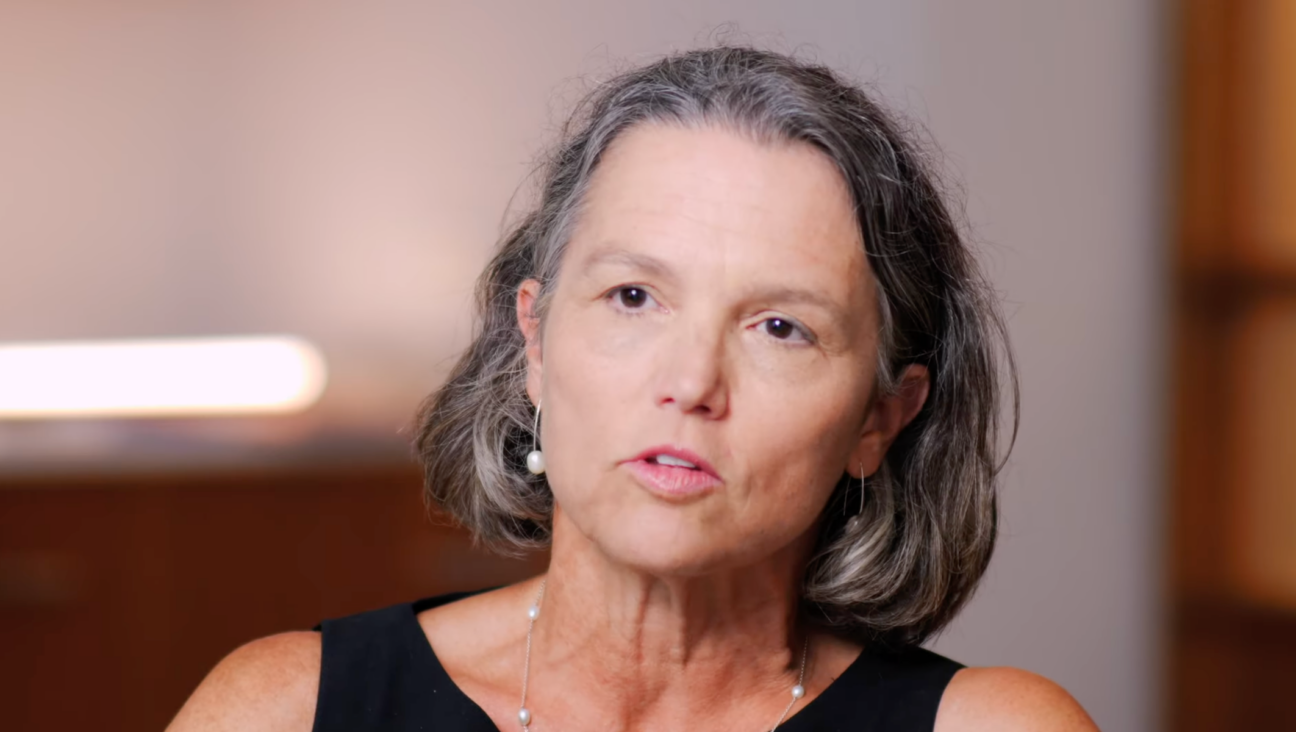

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

- 4

Opinion Is this new documentary giving voice to American Jewish anguish — or simply stoking fear?

In Case You Missed It

-

Film & TV In this Jewish family, everybody needs therapy — especially the therapists themselves

-

Fast Forward Katrina Armstrong steps down as Columbia president after White House pressure over antisemitism

-

Yiddish אַ בליק צוריק אויף די פֿאָרווערטס־רעקלאַמעס פֿאַר פּסח A look back at the Forward ads for Passover products

קאָקאַ־קאָלאַ“, „מאַקסוועל האַוז“ און אַנדערע גרויסע פֿירמעס האָבן דעמאָלט רעקלאַמירט אינעם פֿאָרווערטס

-

Fast Forward Washington, D.C., Jewish federation will distribute $180,000 to laid-off federal workers

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.