Trying To See the World Through the Eyes of Terrorists

The American ambassador in Beirut urged Jessica Stern not to proceed with her mission, but that did not deter her. She made a phone call to her husband in Boston, telling him that if she did not call later that day, he should consider alerting the embassy about her disappearance. Then, she set off to interview Ayatollah Fadlallah, the spiritual leader of Hezbollah.

That interview in Lebanon four years ago proved to be only the first foray Stern would make into the lairs of terrorists. Over the next few years, she traveled to Gaza and Jordan to speak with Hamas followers; West Bank settlements to meet with the Jewish militants responsible for Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination, and Texas and Arkansas to interview anti-abortion activists who kill abortion providers.

With each of her subjects, she said, she pursued the same question: “What makes a person slip over the moral edge?” The encounters, and the answers she found, provide the basis for her book “Terror in the Name of God” (HarperCollins, 2003).

As with that ambassador in Beirut, her approach has not been met with much approval among officials and other terrorism experts, who have dubbed her project a “Prozac” approach to terrorism, and said she has a “worm’s eye view” of the problem.

Sitting down with the Forward over a cup of tea — the same beverage she was offered by the highest leaders of Hamas — Stern explained that in spite of all these objections, “sometimes, you’re just so curious you can’t stop yourself.”

But the motivation for her project extended far beyond that initial curiosity. Stern argues that terrorist acts are commited by people, and if we do not understand the people committing terrorism, “and the pain and frustration that cause it,” we will have trouble stopping them.

Stern, 45, had an established career researching terrorism — as a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and more recently at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government — before she came to this more hands-on approach of interviewing the perpetrators in person.

Stern says her goal in each interview was to “take on the brain of my interlocutor, to really see the world through his eyes.” Empathizing with these men, Stern said, put her into contact with “real evil,” and it was not a gentle experience.

“Afterwards I was shattered,” Stern said. “I would have to just lie on the floor to recover.”

One of the most draining elements of the confrontations was Stern’s simultaneous attraction and revulsion when listening to the beliefs of her interviewees.

In 1998 Stern was invited to a Texas trailer park for an interview with Kerry Noble, formerly second in command at “The Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord,” a Christian cult that had stockpiled arsenic for mass poisonings. As Stern sat in the presence of Noble’s calm confidence, she said, “I found myself envious of Noble’s faith, even as I was horrified by his cult’s plots and crimes.”

Noble told Stern that he had given up his violent dreams, but he remembered his passionate desire to bring down the “Zionist Occupied Government,” which, as he saw it, was leading America into unholy international alliances — with organizations like the United Nations — that weakened the country’s moral fiber.

The fear of globalization and the spread of “post-Enlightenment Western values” is one of the more common traits Stern found among her subjects. In their fears, and their common desire for a theocracy, the terrorists frequently appear to have more in common with each other than with their less extreme co-religionists.

Avigdor Eskin, a Jewish mystic who was implicated in the plot to assassinate Rabin, told Stern of his jealous admiration for Muslim extremists.

“They have real culture, real strength,” Eskin said. “The Muslims, they are ready to fight, ready to die for something. Democratic liberal societies are getting globalized, they are rotten to the core.”

But these common traits mask a wide gulf between the groups Stern discusses in her book. While the Jewish and Christian terrorists mention the personal grievances that led them to embrace their ideologies, they rarely depart for long from the scriptural and ideological defense of their violence. The Muslim terrorists, on the other hand, mention the Koran, but they spend most of their time talking about the immediate and physical experiences of humiliation and loss that drove them to violence.

Throughout the book, the Pakistani mujahadeen and Hamas fighters seem driven into a life of violence by more prosaic concerns: They are looking for an adventure, a sense of purpose or sometimes just a regular paycheck — which gives Stern a great deal of hope that their chosen paths could be changed.

Though the Jewish terrorists command less space in her book than the Christian anti-abortion zealots and the Muslim militants, Stern said that her experience with them was the most personally disturbing.

Stern grew up in Concord, Mass., with a father who escaped from Nazi Germany. From him she learned that “God is in the mountains, not in the synagogue.”

Only in her young adulthood did she begin to find an interest in deepening her Jewish faith and attending synagogue. It was in this spiritually open state that she visited Yoel Lerner, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology-trained mathematician who was a leader in the Temple Mount Faithful, a militant group that hopes to build the Third Temple in Jerusalem.

Like many of the militant leaders she met, Lerner was a learned man, and he quickly showed up Stern’s religious ignorance. “I was susceptible to the notion that I am not a [good] Jew,” Stern said. “I was very susceptible to guilt.”

As she sat in his home in the West Bank, Stern imagined herself moving to the settlement with Lerner and cooking Sabbath dinner with his wife, protected by the great monolith of Lerner’s religiosity. But she quickly drew back in fear of her own attraction to Lerner’s sense of certainty.

Since the interviews ended in 2001, Stern has found herself unable to return to synagogue. She said that she still feels “completely Jewish,” but added, “I just get nervous when I go inside. I see the way organized religion can be abused and used to promote violence and it scares me.”

Even still, she has not lost her fascination with religion and the ways it can be used to justify horrible acts. She hopes that the study she began can be continued in a more scientific fashion, to answer additional questions like: “Why is this leader a more effective recruiter than this leader? And why is this refugee camp a more effective recruiting ground than that camp?”

Stern has talked with a number of people about journeying to Guantanamo Bay to talk with captured Al Qaeda men. But gone are the days when she would venture to the terrorists’ home territory. It’s just too dangerous, she said.

“Since September 11,” Stern said, “America has become an enemy of many groups that might have spoken out before, but now would be willing to take violent action if given the chance.”

And she should know.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

Fast Forward How Coke’s Passover recipe sparked an antisemitic conspiracy theory

- 3

Opinion Stephen Miller’s cavalier cruelty misses the whole point of Passover

- 4

Opinion Passover teaches us why Jews should stand with Mahmoud Khalil

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion I operate a small Judaica business. Trump’s tariffs are going to squelch Jewish innovation.

-

Fast Forward Language apps are putting Hebrew school in teens’ back pockets. But do they work?

-

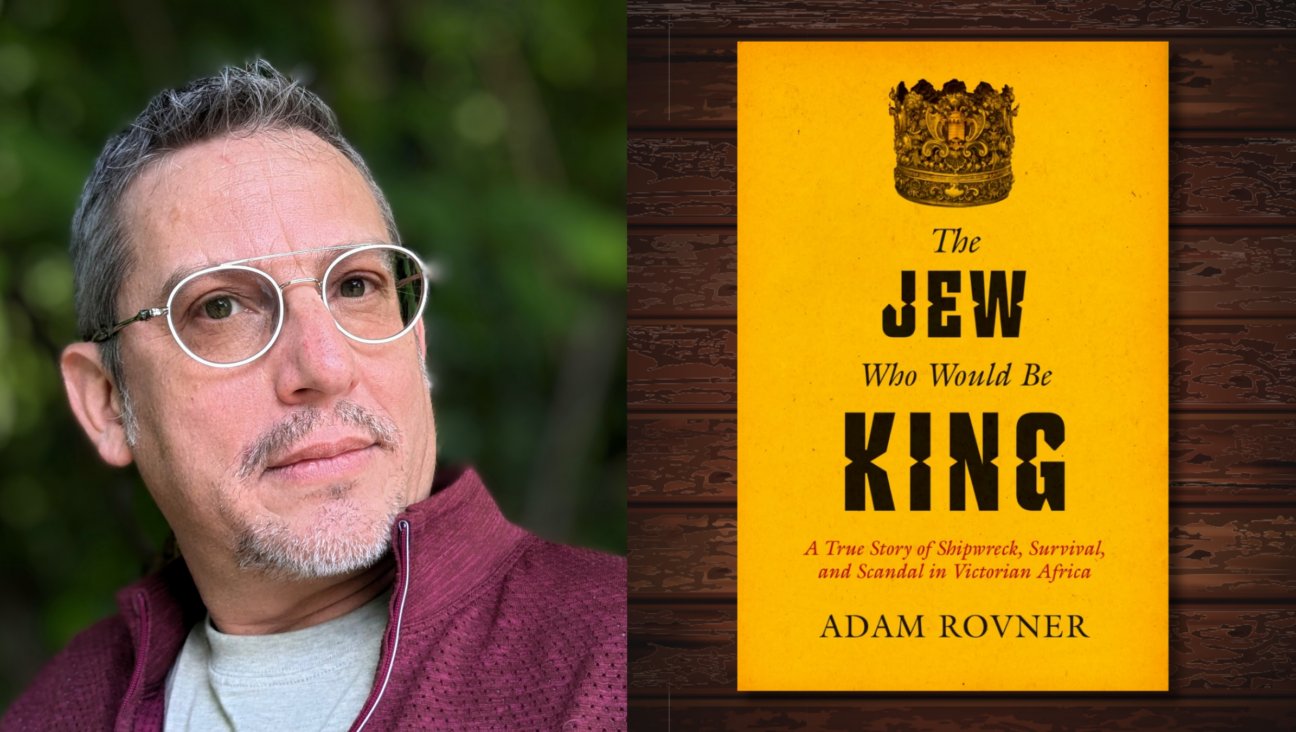

Books How a Jewish boy from Canterbury became a Zulu chieftain

-

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.