WHO LET THE DOGS IN? SHOWING OUR STRIPES Straight to the Sources: What Our Tradition Says About Affiliation

The Jewish Political Tradition, Volume II: Membership

Edited by Michael Walzer, Menachem Lorberbaum and Noam J. Zohar

Yale University Press, 662 pages, $40.

* * *|

Interest in the question of membership in the Jewish collective has been steadily on the increase since the end of the 18th century, both in the Diaspora and in Israel. Against the backdrop of emancipation and liberalization, as well as the establishment of the Jewish state, the phenomenon of the secular Jew — one who blends into non-Jewish society and perhaps even marries a non-Jewish partner, yet remains identified as a Jew — has become increasingly widespread, sparking a plethora of questions. Can a Catholic monk with a Jewish mother and a Jewish father be considered a Jew, since Judaism does not recognize conversion to another religion? Can a Russian

immigrant soldier, the son of a Jewish father and a Christian mother, be buried in a Jewish cemetery after having fallen in the line of duty, even though according to traditional Jewish law he is not Jewish? Indeed, who is a Jew?

The second volume in the series of “The Jewish Political Tradition,” edited by Michael Walzer, Menachem Lorberbaum and Noam J. Zohar, deals with precisely this question, the dilemma of Jewish affiliation. The book, which derives from a series of annual conferences held at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Israel, combines texts from Jewish sources — ranging from the Bible to contemporary literature — with comments and short articles that both elaborate on and argue with these sources. The introduction alone offers views from the Bible, the Mishna, the Talmud and the Aggada, or rabbinic wisdom literature, as well as various thinkers, including Maimonides and the medieval legalist Joseph Karo. Some of the sources presented in the book are translated here for the first time into English, and while the use of certain translations may occasionally be disputed, this alone renders the books of tremendous importance to the student of Jewish history.

The Hebrews went down to Egypt as a family and left there as a people, based on family ties, demographic growth and a clear perception of “the other” — meaning anyone who did not belong to them. But this did not define the Hebrews from within. It was only later that the Hebrew people consolidated its own identity through the covenant of divine commandments received at Sinai

Those divine commandments formed the core of Jewish cultural identity for centuries. Only recently, with the emergence of secularism in the 19th century, did the option emerge of identifying as a secular Jew with the elements of Hebrew and Jewish culture that were connected to the people more than to God.

Regardless of the era, the observance of boundaries has always been vital to a people that wanted to preserve its existence in the Diaspora. Anyone who joined was viewed suspiciously, and anyone who wanted to leave provoked angry reactions. In that manner the group preserved itself.

But how to define a member? The question of membership in the community bore a religious and ethnic nature until the appearance of Zionism. For centuries before, in the absence of a political framework, the Jews created a framework for affiliation based on rabbinic canon law, or Halacha. This was commonly understood and accepted by Jews throughout the world until the dawn of the Emancipation. It is only in the last 200 years that this consensus has been questioned, including with respect to issues such as patrilineal descent. Following the creation of the new state, in which the definition of “Who is a Jew?” became connected to the question of Israeli citizenship, determining who is a Jew and who is not emerged as a legal necessity.

“The Jewish Political Tradition” is divided into six chapters: “Election,” “Social Hierarchy,” “Gender Hierarchy,” “Converts,” “Heretics and Apostates,” and “Gentiles.” In this way, the question of affiliation is actually examined by vertical and horizontal cross-sections. The vertical cross-section classifies the persons who belong within the Jewish framework in a hierarchical fashion (Cohen, Levy, scholars, the rank and file, women, etc.), while the horizontal cross-section relates to the circles surrounding Judaism: apostates, Karaites, “righteous gentiles” who live according to the Noahide Code and people who are totally outside the Jewish orbit. For each one of the issues presented in the book, there is an honest and commendable attempt to set forth a diverse range of opinions and thus to present the problematic nature of the answers, which tend to be presented by their authors as an absolute truth.

Each chapter offers its own gems. The chapter on election — used as a synonym for “chosenness” — presents a diverse range of opinions, from Judah Halevi and Maimonides to Baruch Spinoza and Yeshayahu Leibowitz. Halevi was convinced that the Jewish people were chosen by God and were bestowed with prophetic powers passed on from generation to generation, while Maimonides and Spinoza attempted to present a more rational approach. Leibowitz, for his part, believed divine election to be solely the imposition of the halachic commandments on the Jewish people.

One of the most riveting sections is the chapter on gender, which presents the clear advantage that men have over women in the Jewish framework. This section includes a moving article by Leah Shakdiel, who won a 1988 Israeli Supreme Court case, gaining the right to join a local religious council that did not previously permit women.

The chapter on conversion discusses the way new Jews join the religion through the different streams of Judaism and is followed by an interesting chapter on heretics and apostates, those who lie on the borderline of Judaism. On this subject, Menachem Brinker’s excellent article is particularly worthy of note; it presents the argument between Ahad Ha’am and Yosef Chaim Brenner about secular Judaism, in which the former places heavy emphasis on the cultural side and the latter presents the centrality of the economic aspect.

For all its strengths, though, the book has no small number of weaknesses. With regard to one of the most central questions — the definition of a person as a Jew according to his/her mother’s religious identity — the editors do not sufficiently engage themselves in the intricacies of the issue.

This would have been the place to present the two current definitions of who is a Jew: the Orthodox and Conservative movement position, which declares a Jew to be someone with a Jewish mother, and the definition of the Reform movement, which has deemed anyone with one Jewish parent to be Jewish.

The book also ignores the question of nonreligious conversions, thus falling into the usual trap of discussing conversion according to the different denominations of religious Judaism, without asking what has become a necessary question: namely, how can a secular person join the Jewish collective in a secular way?

Nevertheless, this is an extremely important book, worthy of a place on the modern Jewish bookshelf. Readers of the book may agree with the conclusion that I have reached: The very fact that there are so many definitions regarding the question of membership in the Jewish collective makes it legitimate to add to them, and the 21st century is the time for new definitions to be added to those definitions already in existence.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

- 2

Opinion Trump’s Israel tariffs are a BDS dream come true — can Netanyahu make him rethink them?

- 3

Fast Forward Cory Booker’s rabbi has notes on Booker’s 25-hour speech

- 4

News Rabbis revolt over LGBTQ+ club, exposing fight over queer acceptance at Yeshiva University

In Case You Missed It

-

Theater William Finn, Tony-winning writer of queer, Jewish musicals dies at 73

-

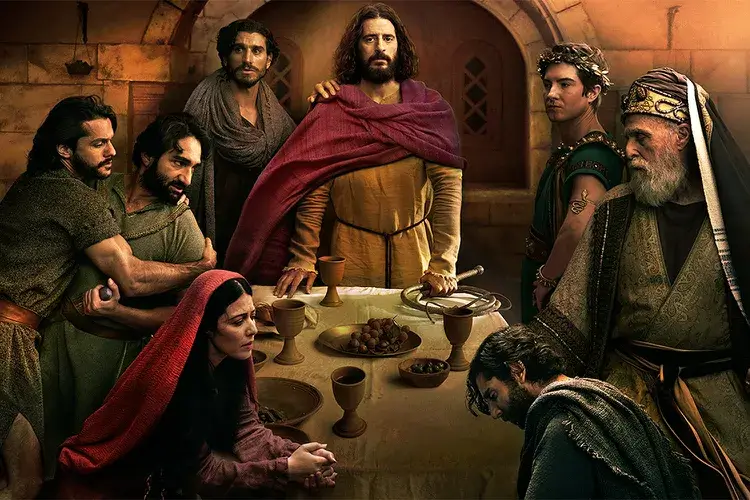

Culture The only good Jews in this hit Christian TV show are the ones who follow Jesus

-

Books The golden age for American Jews is over — and wow was it short

-

Fast Forward AIPAC attacks Democrats who voted to stop arms sales to Israel

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.