Waiting for Abu Mazen’s Altalena

As the Palestinian prime minister, Mahmoud Abbas, tries to stop Palestinian violence with a cease-fire rather than brute force, Israelis and their American supporters keep calling for a “Palestinian Altalena.”

The Altalena was the much-chronicled ship loaded with munitions that the underground, militant Jewish militia, the Irgun, intended to use in Israel’s War of Independence in June 1948. After a dispute over the arms, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion did something most modern Israelis wish Abbas would emulate: Ben-Gurion ordered the ship destroyed, and 16 members of the Jewish underground were killed.

Like other Israelis, I want Abbas, known by his nom de guerre Abu Mazen, to do whatever it takes to stop Hamas and Islamic Jihad from slaughtering Jews — and other Arabs — in our streets. But those who invoke Israel’s internal history to demand that Abu Mazen have his own Altalena moment now, before Israel takes serious conciliatory steps, are not reading that history — or the lessons of the Altalena — correctly.

I was a 13-year-old Irgun member when that ship was destroyed. The incident, and the idea that Jews would do this to other Jews, broke my heart. In fact, after the ship sunk off the coast of Tel Aviv, not far from my home, I joined a small crowd that swam out to it and tried unsuccessfully to retrieve some weapons, which I had hoped to smuggle to our Irgun fighters.

I, like my country, have matured since then and know that no modern state can function unless its armed forces are under one central authority, which was why Ben-Gurion took that step. But I also remember the agony that most Israelis felt when they realized how close we were to civil war. I recall the Irgun leader, Menachem Begin, weeping publicly on a Tel Aviv balcony soon after the Altalena incident while a restive, stunned crowd gathered on the street below.

Ben-Gurion did not decide to provoke that agony and risk national fratricide until the reality of a functioning Jewish state was so close he could taste it. Israel had declared itself independent the previous month, had been recognized as a state by the United States and the Soviet Union — among others — and only needed to defeat Arab armies to fulfill the Zionist dream.

Abu Mazen, though, is much further away from achieving the dream of a two-state solution and the end of occupation. Israelis and their supporters abroad are setting themselves up for disappointment if they continue to expect Abu Mazen to be more far more courageous than Ben-Gurion. At least right now, the kind of armed conflict between Palestinians that would thoroughly crush Hamas and Islamic Jihad would be even more traumatic for them than the Altalena was for us.

In fact, Abu Mazen’s current situation is more similar to Ben-Gurion’s four years before the Altalena incident, when the Zionist leader found that Jews would not help thwart independent militias unless they had concrete hope for political progress. In 1944, after a violent Jewish splinter group, Lehi, murdered a British diplomat, Ben-Gurion’s Palmach forces turned in hundreds of Jewish militants to British authorities, a period known as “la saison,” as in hunting season. But that effort fizzled out, mainly because it lacked popular support, and the Palmach men began refusing to turn in their brethren. The British occupation was still intact, the Jewish state seemed far away and it was simply not the time to risk splintering apart.

Abu Mazen, who has denounced terrorism and the Palestinian intifada, has declared that there will be only one Palestinian security authority and that others should disarm. Thus far, he has tried to reach this goal by proposing a cease-fire and inviting all Palestinian factions to participate in Palestinian democracy.

I wish that Abu Mazen were in a position to do otherwise. But he is not yet able to crack down hard on his underground. Instead of demanding the unattainable — and thereby ensuring that there is no break in the violence — Israel and the United States should hasten the day when Abu Mazen will be ready for his own Altalena moment.

Caught in a pincer between Hamas and Yasser Arafat, Abu Mazen has little credibility or popular support in the Palestinian “street.” But that street can be won over, and his authority can grow, if he negotiates immediate, tangible gains for his people — such as the dismantling of settlement outposts and a settlement freeze — and offers the concrete possibility of a two-state solution. This requires bold decisions on the part of the Sharon government and vigorous American diplomacy to press for such decisions.

If there is a real peace process, and a widespread Palestinian sense that this process could end the occupation and stave off economic disaster, there is at least a chance that Abu Mazen will earn the authority he needs to take on Hamas and Islamic Jihad.

Even though these groups have accepted a temporary cease-fire, it is unlikely that they will disarm and accept the authority of a Palestinian Authority security force. If that refusal threatens to disrupt a promising diplomatic process, and a state is so close that Abu Mazen and his people can begin to taste it, a Palestinian Altalena moment just might happen.

Wishing it would happen sooner will not make it so. Israel’s security forces must do everything possible to protect our citizens. But in the long run, the best way for Israel to protect itself is to bolster Abu Mazen’s authority by taking the steps the United States is now asking it to take, by making President Bush’s “road map” work. Insisting that Abu Mazen ignore the realities of internal Palestinian politics will ensure that the road map, and the region, get nowhere.

Moshe Maoz is a professor of Islamic-Middle Eastern studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He served as assistant adviser on Arab issues in Israel to Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion from 1960 to 1962.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

Fast Forward How Coke’s Passover recipe sparked an antisemitic conspiracy theory

- 3

Opinion Stephen Miller’s cavalier cruelty misses the whole point of Passover

- 4

Opinion Passover teaches us why Jews should stand with Mahmoud Khalil

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion I operate a small Judaica business. Trump’s tariffs are going to squelch Jewish innovation.

-

Fast Forward Language apps are putting Hebrew school in teens’ back pockets. But do they work?

-

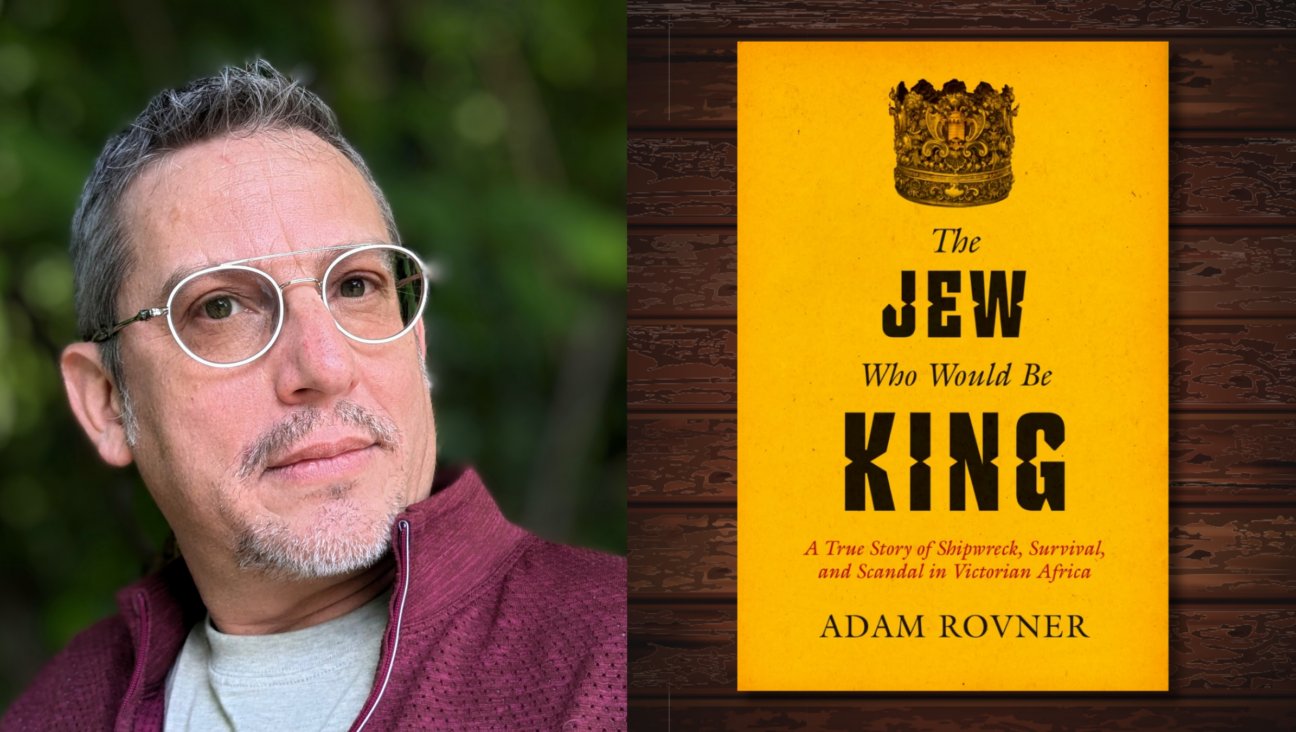

Books How a Jewish boy from Canterbury became a Zulu chieftain

-

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.