Let’s Do The Time Warp

Think 1980s. Think “Miami Vice” pastels. Think disco and bad 1970s hair. Think age 13. For those who delight in the simchas of yesteryear, there’s Barmitzvahdisco.com, a Web site dedicated to the bar mitzvah — in all its glitz and glory. Sometimes, some people just want to luxuriate in the sentimental kitschiness of “when we were shtetl fabulous,” as the site boasts fondly.

At first glance, it looks like a one-joke Web site: an electronically accessible pictorial history of Diaspora folkways, predominantly from the 1970s through the 1990s. A photo gallery features a host of images resurrecting the sights and sounds of the bar/bat mitzvah celebration. But even if the site were meant as a joke, it would be a multilayered one. After all, the site is a time capsule filled with ephemera, one that’s on its way to becoming a cultural historian’s gold mine.

There are monogrammed matchbooks and thematic T-shirts. “I had a Phantom of a time at Josh’s bar mitzvah,” says one, while another sports a faux Page 1 headline: “Guests Rock All Night at Corey’s Bar Mitzvah.” The tchotchkes and T-shirts, however, pale in comparison to the artistry of the cakes: On one, a mini-bar-mitzvah-boy water skis around Manhattan; another takes the form of an electric guitar.

Cheesiness abounds at theme-party bar mitzvahs that run the gamut from science-fiction superheroes to the pastel suits of “Miami Vice.” At a 1987 celebration, for example, a group wearing New Wave wigs and sunglasses, animal-skin suits and chains poses around a microphone. Impersonators are welcome guests, with Michael Jackson, Burt Reynolds and Dolly Parton look-alikes among them. And, lest anyone forget the delights and downfalls of the disco era, spandex and “Jewfros” are in abundance, not to mention the ubiquitous three-piece suit.

But what does it all mean? According to Nick Kroll, one of the site’s founders, the site provides the opportunity to “look back at the awkward times of adolescence and to find humor” while recording a piece of the collective history of the Jewish people. In no way, he said, is it a “condemnation of the Jewish community.” Even if many of the fashion choices do by now seem questionable.

Barmitzvahdisco.com is the brainchild of three bar/bat mitzvah veterans: Roger Bennett, 32, vice president of strategic initiatives at the Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies; Kroll, 25, an actor-comedian-writer, and Jules Shell, 27, a documentary filmmaker. What began as an informal exchange of memorabilia among friends evolved, according to Bennett, into a passion.

As their enthusiasm grew, Bennett told the Forward, individual “memories of bar mitzvah[s], and the transitional nature of adolescence” came to the fore, while at the same time revealing the “collective story” of Jews in the contemporary era. For her part, Shell said she had been filming a bar mitzvah when she realized there was “something connecting all our stories.”

The site thrives on this overlap of cultural experience by being interactive. According to Kroll, visitors are excited about reliving their own bar mitzvahs, and they seem to relish the opportunity to send in their own ephemera and to comment on what’s posted on the site. Beneath a picture of some wacky-looking entertainers, for example, someone has written: “You’re beginning to scare the children.”

As Bennett, Kroll and Shell emphasize, the site serves a “micro” purpose in relating individual stories while pursuing a “macro” agenda of positioning these individual stories within a broader cultural context.

The site’s founders admit to an explicit ethnographic agenda, which may well serve as a treasure trove for cultural historians. After all, bar mitzvahs aren’t just about parties — even if “Michael” had a faux $100 dollar bill made up with the words “in fun we trust” and a picture of himself. There are pictures of children reading from the Torah and prayer books, with one formal photograph from a 1987 New Jersey bar mitzvah showing a picture of the boy superimposed over the “Gates of Prayer.” Still another features a copy of a bar-mitzvah lexicon, from aliya to wimpel.

These artifacts of popular culture do more than help us bask in sentimentality. After all, Jewish historiography is not restricted to the study of theology and halachic rulings. It relies equally on the way broader cultural trends filter into the rites of Judaism.

The response to Barmitzvahdisco.com has been tremendous. Bennett, Shell and Kroll hope that visitors will continue to share and contribute their personal bar mitzvah ephemera, which they plan to include in a book, based on the site.

The very existence of the Web site also raises questions about Judaism at the end of the 20th century, and some of these questions are left unanswered. As historians puzzle over why our Jewish ancestors employed images from Greek mythology in their synagogues, so too might our descendants be confounded by a Dolly Parton impersonator dancing with the bar mitzvah boy. At a time when books on the individual’s spiritual journey proliferate, a Barmitzvahdisco.com book will be a welcome addition, helping us to understand how religious observance plays out on the popular level.

Of course, it would also make a nice contribution to any modern Jew’s collection of coffee-table kitsch.

Daniel Bronstein, a rabbi and teacher in New York City, is a doctoral candidate in Jewish history at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion Yes, the attack on Gov. Shapiro was antisemitic. Here’s what the left should learn from it

-

News ‘Whose seat is now empty’: Remembering Hersh Goldberg-Polin at his family’s Passover retreat

-

Fast Forward Chicago man charged with hate crime for attack of two Jewish DePaul students

-

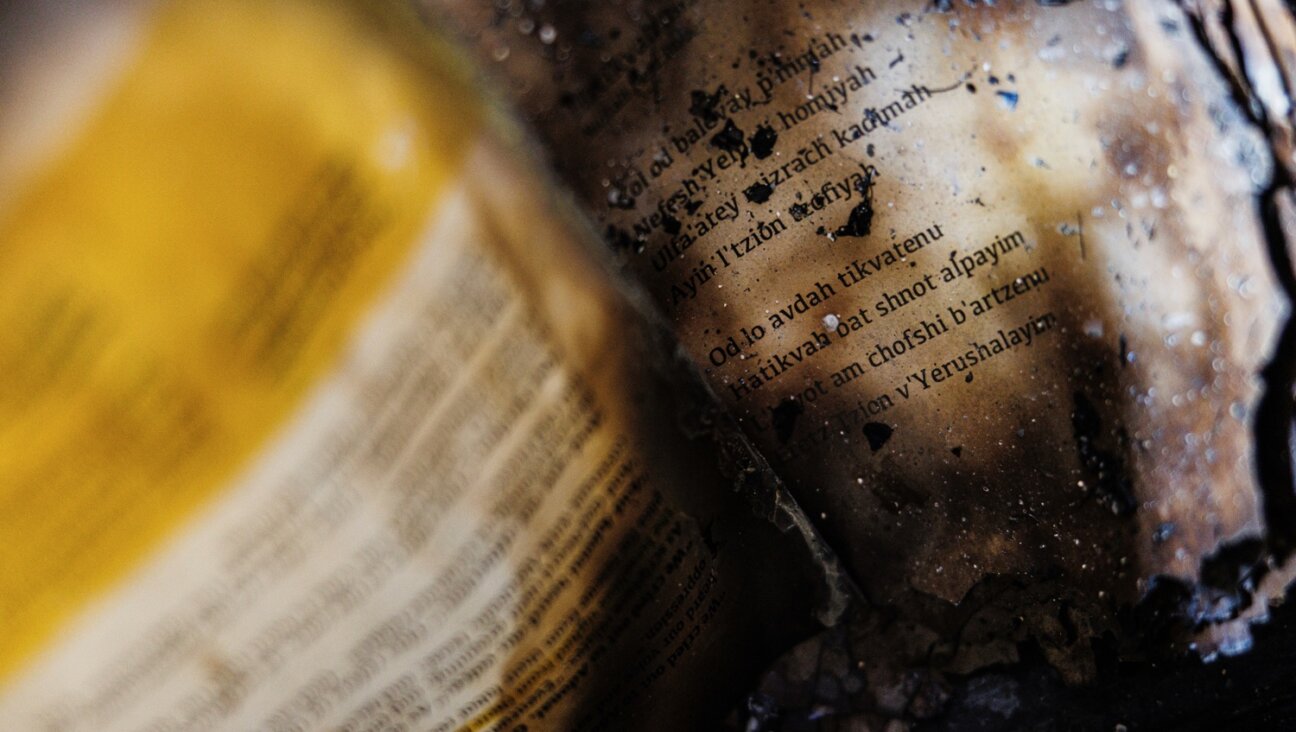

Fast Forward In the ashes of the governor’s mansion, clues to a mystery about Josh Shapiro’s Passover Seder

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.