Whither Saudi Arabia?

The Two Faces of Islam: The House of Sa’Ud from Tradition to Terror

By Stephen Schwartz

Doubleday, 336 pages, $25.

* * *|

Sleeping with the Devil: How Washington Sold Our Soul for Saudi Crude

By Robert Baer

Crown, 256 pages, $24.95.

* * *|

Hatred’s Kingdom: How Saudi Arabia Supports the New Global Terrorism

By Dore Gold

Regnery, 309 pages, $27.95.

* * *|

It has been 37 years since I received orders to report as a junior diplomat to the U.S. Embassy in Jiddah, Saudi Arabia. As I had just completed a grueling course in colloquial Moroccan Arabic, which was unintelligible in Saudi Arabia, I went kicking and screaming — figuratively, at least figuratively. What I found there was utterly fascinating: a proud, intensely private and traditionalist people, newly flush with oil money, rushing headlong from somewhere between the seventh and the 18th century into the modern world.

Saudi Arabia was not a household name in those days. It had few of the modern amenities that are associated with the kingdom now. King Faisal shunned the radical Arab nationalism of the Egyptian president, Gamal Abd al-Nasser, against whom he was fighting a proxy war, with covert Israeli aid, on the side of Yemeni royalists in a civil war against the Egyptian-backed republicans. Saudi Arabia had proved a staunch friend of the United States, and following the Arab defeat the following June in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, Faisal was one of the few Arab leaders to maintain friendly diplomatic relations with the United States.

Fast forward and the picture is totally changed. Saudi Arabia became a household name in the 1970s when it led the Arab oil embargo against the West, and again in 1990 to 1991 when American troops landed on Saudi soil to repel Saddam Hussein from Kuwait. The Saudis even put up over $50 billion to pay for the war. But post-September 11, 2001, things have been different. Fifteen of the terrorists that day were Saudi citizens, and their leader, Osama Bin Laden, though stripped of his citizenship, was still a Saudi in the eyes of Americans, and was funded by private donations from the Gulf oil states, including Saudi Arabia.

What had happened to the staunch personal friendships that existed between the Saudi people and the thousands of Americans who went there to share in the oil wealth and protect the kingdom from outside threats? What happened to the close cooperation between the Saudi government and the American government, dating back to World War II, on a whole range of political, economic and military issues at considerable political costs to both countries? Three books have recently been published, each in its own way challenging whether Saudi Arabia was ever any true friend in the first place and claiming that the relationship was based on the self-serving American desire for oil revenues and on the self-serving Saudi desire to perpetuate its own corrupt, anti-democratic governmental system and its terrorist campaign to propagate its hate-filled Wahhabi ideology for Islamist world domination.

In “The Two Faces of Islam: The House of Sa’ud from Tradition to Terror,” Stephen Schwartz, former Washington bureau chief of the Forward, asserts that mainstream Islam is not the face of the enemy in the war against terror. Rather, the enemy is a fanatical, hypocritical, totalitarian and violent version of Islam called Wahhabism, born in central Arabia, that forms the ideological base of legitimacy for the Saudi regime. The book is basically historical, beginning with the birth of Islam and moving on to the birth of Wahhabism in the 18th century and creation of the Saudi state in 1932, and finally, to the events leading up to September 11 — a mélange of the rise of militant secular Arab and Islamic organizations and oil politics and the rise of militant Wahhabi holy war under the tutelage of Saudi Arabia.

“The Two Faces of Islam” is by far the most erudite of the three books, as well as the most sweeping in scope. Schwartz is sympathetic to what he calls “mainstream” Islam, and his scathing view of Wahhabism was shared by many mainstream Muslim scholars and clerics of the 18th and 19th centuries. But the book’s major flaw is Schwartz’s lack of perspective on the human dimension of his subject. He evinces virtually no understanding of Saudi behavior or of the impact of the physical and intellectual environment that molded it. It would be presumptuous to suggest than any Westerner can see the world through Saudi lenses — so different are Saudi and Western cultures. Still, not to take those differences into account is to risk misinterpreting Saudi behavior as an unending stream of inconsistencies and irrationality. Schwartz appears to have fallen into that trap. To him, apparently, Saudi behavior is driven exclusively by the basest intentions and motivations. True, he demonstrates some familiarity with other Muslims societies. He was an interfaith activist in Kosovo and Bosnia; but little understanding

of Saudi behavior can be gained from experience among non-Arabian Muslim populations. In the Islamic world, as in the Western world, one size does not fit all.

Saudi behavior is shaped first and foremost by its ancient and highly conservative Arabian desert culture, which in the seventh century became permeated with Islamic values. That culture, which has remained remarkably stable to the present, is nevertheless now under unbelievable stress as it collides with the secularizing and dehumanizing effects of oil-financed modernization. The extraordinary thing about Saudi culture is not that it has resisted modern pop culture, the West’s legacy to the world, but that it has maintained its own cultural identity and values despite the onslaught of modernization. In a world where family structures are disintegrating, the basic unit of Saudi society is still the extended family. One’s first loyalty is to one’s family, whose lineage can be traced back to Ismail, or Ishmael, not to the Saudi monarchy, which can be traced back only to the 18th century, much less to the Saudi nation, which was created only in 1932. Saudi Arabia is a society run by the elders of extended families who are collectively ruled by the elders of the royal extended family, not a country of individuals ruled by an individual ruler. In this context, the ancient desert culture and customs and the Islamic values and mores of the royal family are the same as those of any other Saudi family. Not to understand this is not to understand commercial, political, social or religious practices in the kingdom.

This is not to challenge the factual content of the case Schwartz presents, highlighting sins of omission and commission attributed to Saudis leading up to September 11. I do challenge, however, the accuracy of his portrayal of Saudi society overall as corrupt, intolerant and vicious, and the doctrine of the Wahhabi reform movement as a doctrine of hate. Such broad generalizations unjustly stereotype a society and its religious beliefs.

Robert Baer is a former CIA case officer, specializing in covert foreign intelligence collection, with experience in the Middle East. In “Sleeping with the Devil: How Washington Sold Our Soul for Saudi Crude,” he seeks to trace how American public and governmental greed for oil revenues created an unholy alliance with Saudi Arabia, whose Islamic monarchy he sees as submerged in greed, corruption and Wahhabi extremism. The book is essentially a collection of personal anecdotes strung together with his personal observations and comes across as war stories that a group of retired CIA case officers might presumably relate to each other, suitably embellished and embroidered, late one night over beers.

The book’s chapters all bear evocative titles such “We Deliver Anywhere,” “Pavlov and His Dogs” and “In the War Against Terrorism, You Lie, You Die.” The pulp-spy-novel effect is reinforced by frequent blacked-out sections, presumably to represent sections censored when the manuscript was vetted by the CIA, as published works of all former CIA employees must be. One can only speculate on the degree to which the author and or the publishers felt that the blackouts would attract potential readers with a prurient interest in secret stuff.

Although Baer exhibits more street smarts than the other two authors, and is relatively more candid and less polemical, his book is far less sophisticated. Gaps in his knowledge of petroleum economics, Islam and Islamic law, and even some of the more rudimentary and easily available facts concerning the House of Saud are quite evident. More interesting, however, is the tone. With its portrayal of a world of perfidy, greed and ineptitude, the book struck the reviewer as written in rage — rage directed not simply at the Saudis and their Wahhabism, but also at American businesses and their Washington supporters, both willing to sell their souls for a barrel of Saudi oil. Rage, too, at the culpability of the CIA, the State Department and the FBI, and even indirectly against Israel.

In the end, he focuses on oil, not hate: “Like it or not, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia are joined at the hip,” he writes. “Its future is our future.” His solution, if the Saudis do not shape up, is simply to take their oil fields by force, and he outlines how that might be done. Whatever one may think of a policy of grabbing whatever one wants from whomever one does not particularly like, his preference clearly places a higher priority on the vital strategic importance of Saudi oil than on the Saudi contribution to Islamist terrorism.

Dore Gold, author of “Hatred’s Kingdom: How Saudi Arabia Supports the New Global Terrorism,” is a former Israeli envoy to the United Nations and foreign policy adviser to former Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The scope of his book is narrower than Schwartz’s, beginning with the Wahhabi revival in the 18th century and continuing to the present. Like Schwartz, Gold characterizes Wahhabism as a militant offshoot of mainline Islam, but his emphasis is more narrowly focused on its projection of hatred, a term that is used repeatedly and which appears not only in the title but in the titles of two concluding chapters as well. Though superficially historical in organization, the book is far more polemical in style, with Gold appearing rather like a prosecuting attorney laying out a case. Wahhabism, he writes in a typical passage, “is nothing less than the religious and ideological source of the new wave of global international terrorism,” exemplified by the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Aside from a highly selective choice of citations, uniformly pejorative, from noted commentators — his expert witnesses — he cites at length incendiary Wahhabi rhetoric and intelligence reports on Saudi charitable support for groups engaged in terrorist acts, his evidence. He concludes his case by arguing that Saudi Arabia must be forced to stop supporting Wahhabi hatred and terrorism in the name of Islam.

By portraying Wahhabism as a political ideology of hatred in which unsanctioned political violence is justified by jihad, Gold ignores the purely religious focus of its central doctrine, Tawhid. The essence of Tawhid is the all-encompassing oneness of God (wahid means “one” in Arabic), as expressed in the profession of faith, “There is no god but God, and Mohammed is His messenger.” Wahhabism teaches that communion with the one true God is accomplished neither through mysticism nor rationalism — a heated debate in the early years of Islam — but only through submission to God’s will as revealed in the Koran and the Sunna, Islam’s “oral law,” and by carrying out God’s will through deeds, both personal and corporate, to uphold virtue and suppress evil. Those deeds constitute jihad in its broadest sense, and are to be carried out by peaceful means and not just through force. Doctrinally, whatever the excesses of individual Wahhabi clerics and their followers might be, they cannot be blamed solely on the teachings of Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab any more than the excesses of American Protestant clerics can be laid at the feet of John Calvin or Martin Luther.

Gold’s reliance on textual analysis also obscures the influence of historical changes in political and social conditions on cycles of violence and nonviolence. Militant jihad decreased somewhat with the decline and fragmentation of the Abbasid Caliphate in the 11th and 12th centuries, not because of a change of belief but because of a change in the political environment. But in 18th-century Arabia at the time of Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, tribal warfare was still endemic. Tribal warriors flocked to the banner of Tawhid not to make peace but to add new meaning and purpose to their ancient warring way of life. By the 20th century, however, Saudi tribal warfare had disappeared. In 1929, at the battle of Sibila, King Abd al-Aziz crushed the Ikhwan, his Wahhabi tribal warriors who, disgruntled over efforts to resettle them as peaceful farmers, had risen up against him. It was the last major Bedouin battle in history. From then until after World War II, with the exception of a brief war with Yemen in the 1930s, Saudi Arabia had no standing army.

Taken together, these three books do more to detract from than to add to the understanding of Saudi Arabia, its people, its government and its religious creed. Understanding Saudi Arabia does not absolve Saudis from responsibility in aiding and abetting the new global Islamist threat. The record is clear enough on that count. But greater understanding does increase the chances of better analyzing the true nature of our mutual interests and antagonisms and, taking both into account, of formulating more effective policies to maximize the one and reduce the other.

The books also detract from the understanding of the nature of terrorism and the new global terrorist threat that presumably was the motivating factor in authoring them. Blaming Saudi Arabia and Wahhabism as the single greatest source of support for global Islamist terrorism obscures the many complex factors that contribute to terrorist behavior no matter who the terrorists are and what cause they seek to further. Terrorism is seldom a simple matter of brainwashing, as Gold claims. Studies of terrorist behavior show that incendiary ideological rhetoric, written or oral, is not in isolation likely to spawn terrorists. A predisposition toward violence must generally be present to begin the shift toward extremism. The causes of that predisposition are infinite — psychological, sociological, demographic, economic and political — and vary with each individual. Once that threshold is reached, religious, ethnic, national or political ideology, or some combination of them, may then be used as justification to commit acts that otherwise would seem reprehensible. But rarely is an extremist interpretation of ideology so intellectually compelling in the absence of a predisposition to violence as to result in terrorist behavior.

In the 1960s, militant Wahhabi rhetoric was as incendiary as it is now, but few were listening. Arab and Muslim youth predisposed to violence listened to nationalist, socialist and Marxist rhetoric. Since then, Islamist rhetoric has replaced socialist and Marxist rhetoric as the vehicle for expressing political disaffection leading to violence, but Wahhabism is only one of several sources of Islamist ideology; militant jihad is not the exclusive property of Wahhabism. Many factors caused the shift to militant Islamicism , including the discrediting of Nasserism after the 1967 defeat, and in particular, the shared experience of thousands of trained, multinational Muslim guerrillas, the mujahidin, who fought against the Soviets in Afghanistan with the support of the United States. In Central Asia, the collapse of the Soviet Empire was a major factor.

What made Islamist terrorism a global threat, however, aside from the revolution in communications, transportation and weapons technology, was not ideology but the appearance of a charismatic leader with the extraordinary vision and organizational skills: Osama Bin Laden. He raised the consciousness level of discontented Muslim youth from local political grievances to a global cause. Getting rid of him will not rid the world of terrorism, but neither will fixating on one country and one puritanical religious reform movement. Indeed, the means to commit terrorist acts are too cheap, too available and too tempting ever to be eradicated. The best we can do is to seek to keep this evil within manageable proportions in order to provide basic security for all people.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion Yes, the attack on Gov. Shapiro was antisemitic. Here’s what the left should learn from it

-

News ‘Whose seat is now empty’: Remembering Hersh Goldberg-Polin at his family’s Passover retreat

-

Fast Forward Chicago man charged with hate crime for attack of two Jewish DePaul students

-

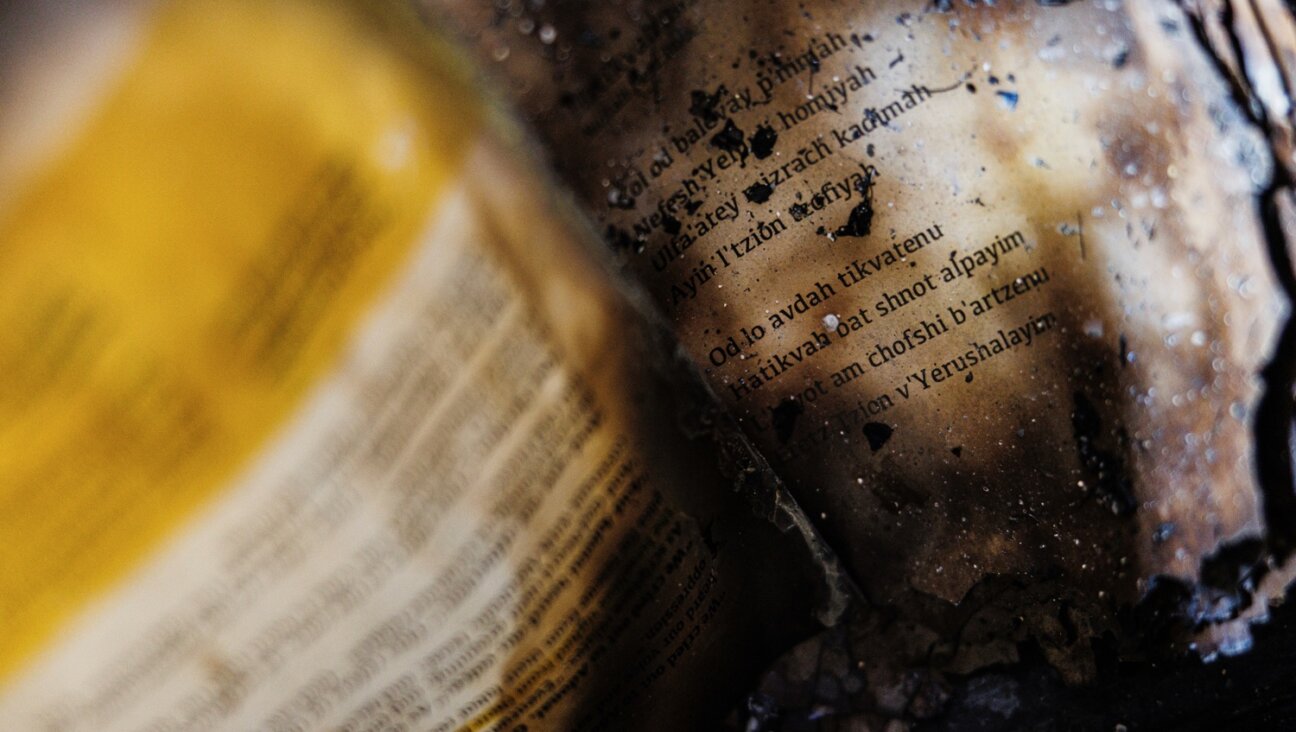

Fast Forward In the ashes of the governor’s mansion, clues to a mystery about Josh Shapiro’s Passover Seder

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.