Holier-Than-Thou Screeds, Circa 1905

Over the past century, not much has changed in the way American Jews mark the High Holy Days. Then, as now, Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur had as much to do with excess, with spending gobs of money on new clothes, lavish meals, elaborate greeting cards and expensive synagogue seats as they did with restraint and introspection.

Back then, however, this behavior occasioned considerable public comment, where today it does not. Year after year, well into the interwar era, the pages of Jewish newspapers were filled with overt expressions of dismay at the way American Jews typically conducted their affairs. Taking their cue from the liturgical practice of breast-beating, American Jewry’s cultural authorities indulged in its sociological equivalent, finding fault with some of the more troubling aspects of modern Jewish life, from the idiosyncratic, episodic nature of synagogue attendance to women’s fashions.

The phenomenon of “Yom Kippur Jews,” those who attend services three times a year only to absent themselves for the remaining 362 days, generated editorials by the handful. When the High Holy Days arrive, American Jews “suddenly come up out of the ground for the purpose of repeating the ancient prayers,” related the American Hebrew in 1905, puzzled by this momentary “shiver of religiosity.” What is it about American Jewry, it wondered, that accounts for this behavior?

A year later, when much the same thing threatened to happen, the American Hebrew again took American Jews to task for failing to support their synagogues on a regular basis. Religious life in the New World cannot flourish unless American Jews hold themselves accountable, it editorialized. Where in Europe synagogues were funded by the government, the American synagogue was wholly dependent on the financial good will of its members, making it the most democratic of institutions. Be sure, then, to support your local synagogue, charged the American Hebrew. It’s your duty as Jews and as Americans.

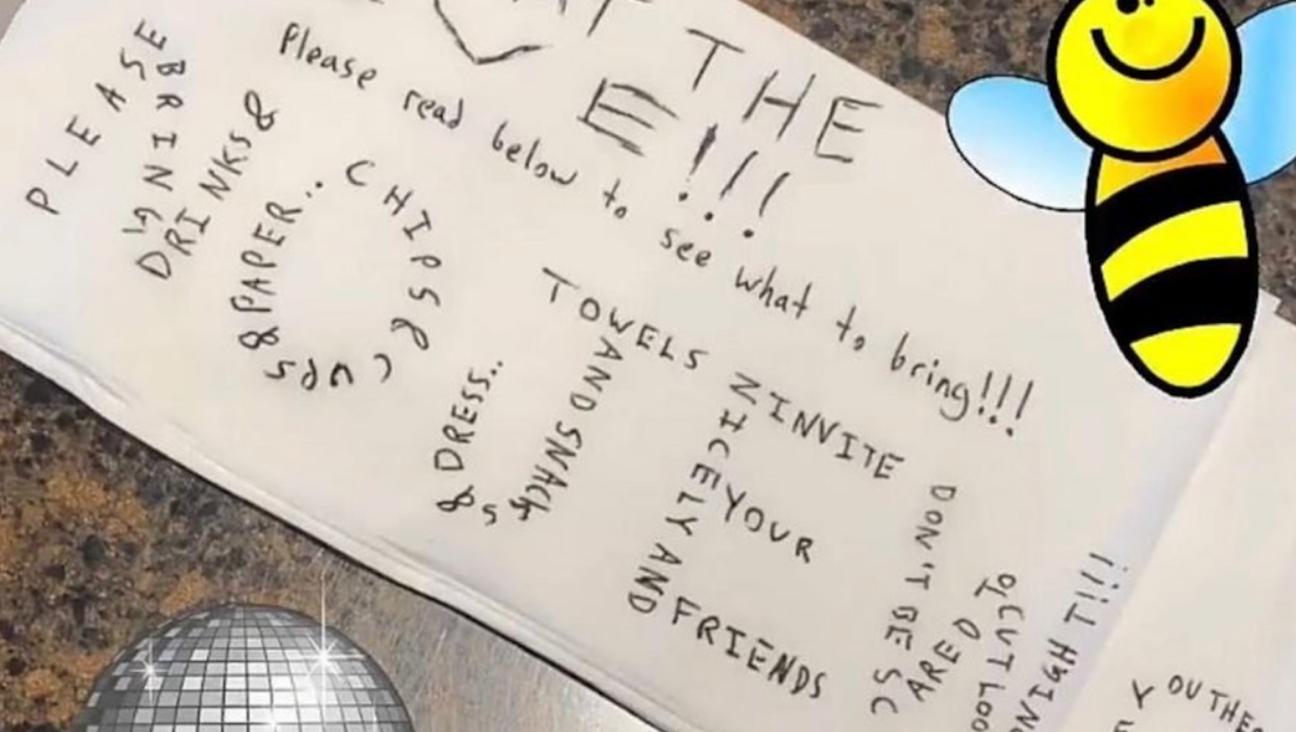

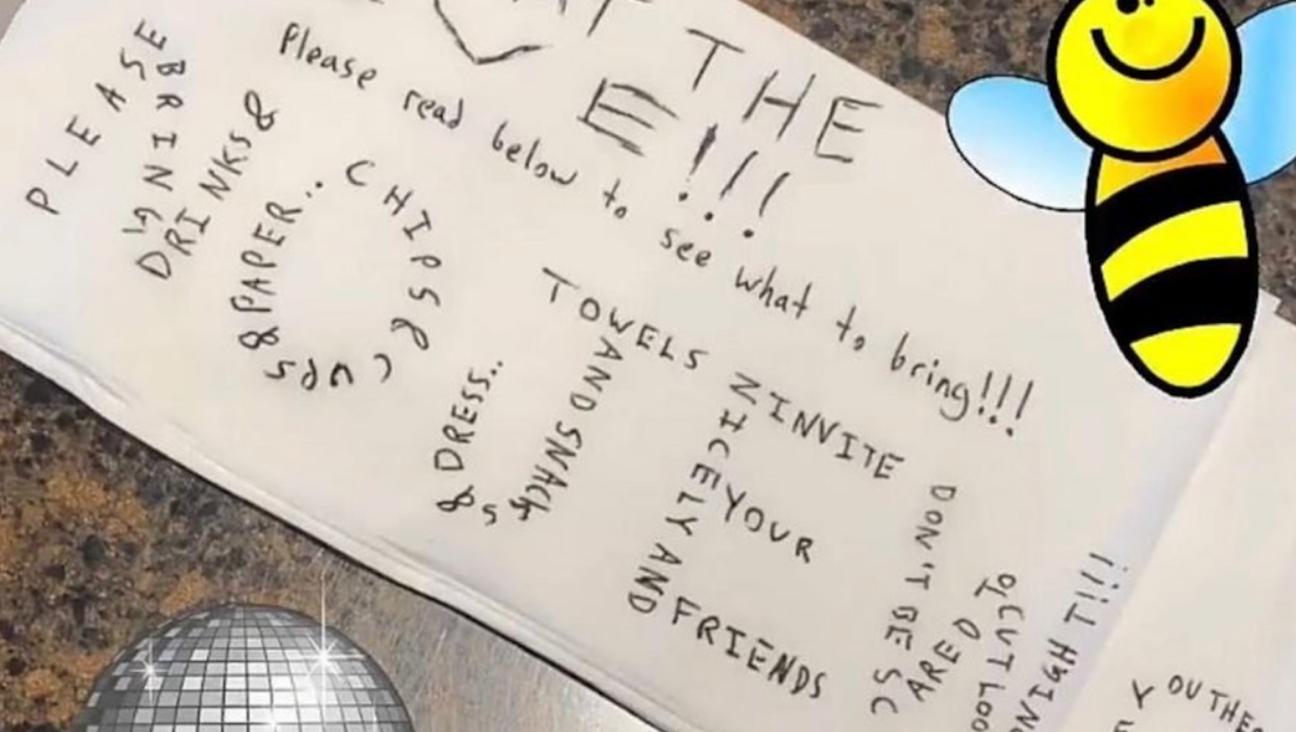

Not surprisingly, those who refused to step foot in a house of prayer, preferring instead to “flaunt their atheism” by marking Yom Kippur with a sandwich or, worse still, by attending one of a number of so-called “Yom Kippur Balls,” also aroused the indignation of the more traditionally minded press. In an act calculated to “antagonize” the religious Jews of Chicago, or so reported the Jewish Daily Courier in 1906, several Bundists actually went so far as to stand in front of a number of Windy City synagogues and distribute invitations to a Yom Kippur dance. That same year in New York, fistfights broke out on Yom Kippur between two rival groups of freethinkers. The police, reported the press, had to step in to “disentangle the participants.”

Almost as disturbing, it seems, was what women wore to synagogue. For several weeks in 1884, the pages of the Jewish Messenger carried heated exchanges among readers who weighed in on what they took to be the extravagant, discordant nature of women’s attire. “It seems to me about time that our rabbis and wise men should devise some uniform bonnet and dress for Jewesses on Yom Kippur,” declared one male worshiper whose sensibility, both religious and sartorial, was apparently affronted by the sight of “ladies in blue and black feathers, in white and red hats, in green and brown silk, in all the colors of the rainbow.” What we need today, he said, is a “little less style and a little more sincerity.” His male co-religionists agreed. Why is it, added another, that “our Jewesses glitter and glimmer” when at prayer? “Is our Temple, that sacred edifice, the place for the gathering of gaudy styles? Should Fashion have its bazaar there? No!”

Women, to be sure, viewed things quite differently. For one thing, they rejected the idea that looking good invariably stood in the way of prayer: A woman could be dressed to the nines and still feel profound religious emotion, they insisted. For another, many felt strongly that fashion was a private matter, not a communal one. One member of the gentler sex, wittily styling herself “Flora Furbelow,” took great umbrage at the notion that what she wore should be a topic of collective concern and, in no uncertain terms, told the Jewish Messenger to butt out.

“We are living in America,” she said, “and if we [women] choose to wear a bottle green dress, a red bonnet and a purple feather on Yom Kippur, I say it’s nobody’s business.” Amen to that!

To all the Flora Furbelows, Bundists and shul-goers among us, I bid you a shana tova. Happy new year.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 3

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

- 4

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

In Case You Missed It

-

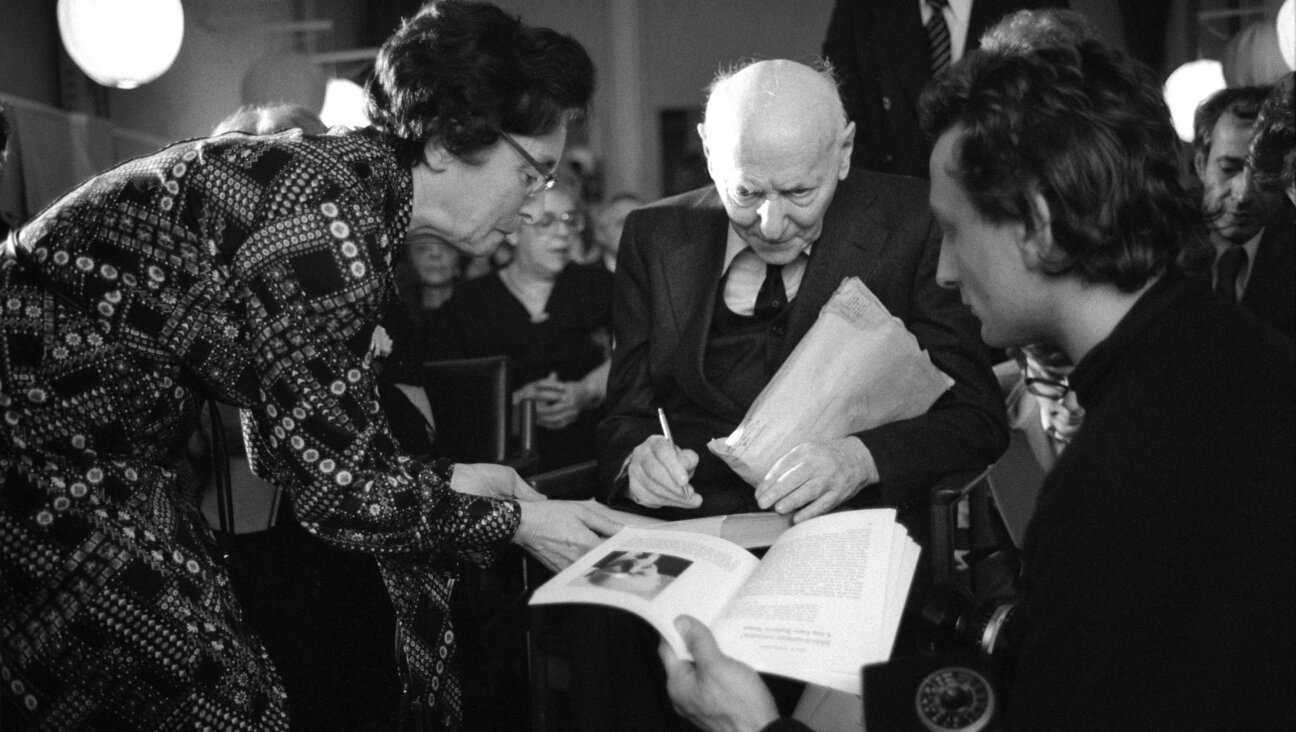

Yiddish יצחק באַשעװיסעס מיינונגען וועגן די אַמעריקאַנער ייִדןIsaac Bashevis’ opinion of American Jews

אין זײַנע „פֿאָרווערטס“־אַרטיקלען האָט ער קריטיקירט זייער צוגאַנג צום חורבן און צו ייִדישקײט.

-

Culture In a Haredi Jerusalem neighborhood, doctors’ visits are free, but the wait may cost you

-

Fast Forward Chicago mayor donned keffiyeh for Arab Heritage Month event, sparking outcry from Jewish groups

-

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.