Wooden Synagogue Project Abandoned

BERKELEY, Calif. — A Modern Orthodox congregation that hoped to build a replica of the wooden synagogue of Przedborz, Poland, has reluctantly abandoned its dream after failing to garner national financial support for the project.

Instead of re-creating the famous 17th-century structure destroyed by the Nazis, Congregation Beth Israel will spend the $2 million raised so far on a more typical modern building.

Re-creating the peak-roofed Przedborz shul would have required at least $3.5 million. But despite a nationwide appeal and extensive publicity, the 160-family congregation couldn’t translate enthusiasm into pledges.

“We got a lot of friendly interest but it didn’t result in large checks,” said Friedner Wittman, a chairman of the congregation’s Wooden Synagogue Committee, which was dissolved at a board meeting last week.

Had the fundraising effort succeeded, Beth Israel would have been the first congregation to completely recreate an Eastern European synagogue. The Przedborz synagogue — built in 1636 in a shtetl located between Warsaw and Krakow — was considered one of Poland’s loveliest, with elaborate woodwork and a carved ceiling adorned with bright colors and jewels. It was a popular tourist site during the 1920s and 1930s and was considered a national gem.

Gina Nirenberg Kimelman, 79, a Holocaust survivor who lives in San Mateo, Calif., is one of just a handful of people who remembers the building. As a child, she attended Sabbath services there with her grandmother, who lived across the Pilica River from the synagogue.

“The outside was old wood and dusty, but when you opened the door, you were in heaven,” Kimelman sighed. “It was roomy and light…. It was a mechiyah [joy] to go there.”

The Nazis razed it in 1942 and slaughtered or deported the town’s Jewish residents to concentration camps.

Photographs and architectural renderings of the building, which was remodeled in 1760, were preserved, however, and later reprinted in a book. Congregation Beth Israel used those plans as the basis for designing a historically faithful recreation with modern safety features.

Construction and endowment costs were initially budgeted at $8 million in 1999, said Denise Resnikoff, Beth Israel’s president. The project appeared to be off to an auspicious start. Honorary committee members included such luminaries as playwright Tony Kushner, Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel and artist David Moss. But they weren’t necessarily major donors, Resnikoff said, and if they did contribute, “we’re not talking about significant funds.”

The project was scaled back to $3.5 million last year as fundraising efforts lagged. Even that goal proved unattainable. Nearly all of the $2 million in pledges and contributions came from the congregation itself, which draws about 130 worshippers, many of them professors and students at the University of California, to weekly Sabbath services in a cramped, mold-infested building that dates to 1924.

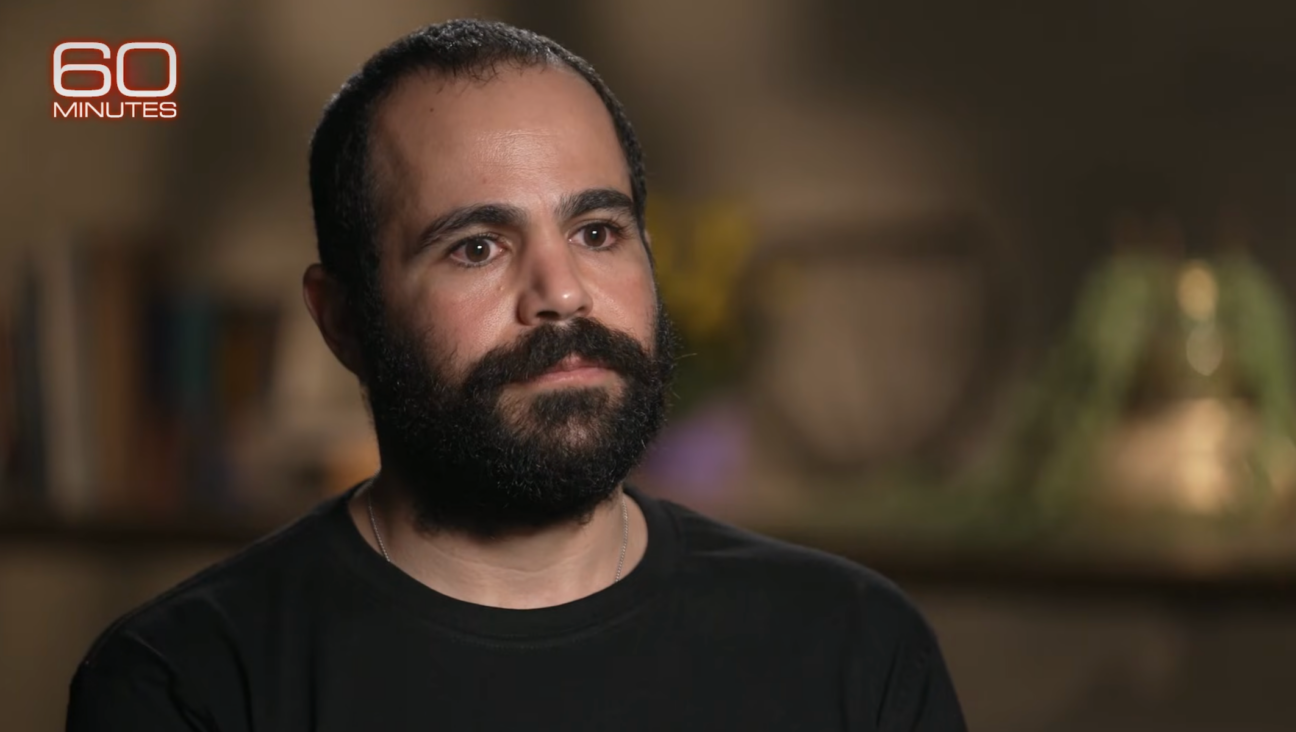

The congregation ultimately could not surmount the mindset among potential donors and grant-makers that it was raising money for a new synagogue, rather than creating an American Jewish landmark, said Beth Israel’s rabbi, Yair Silverman.

“This had the potential to be a national statement that the architecture of Eastern Europe continues to resonate,” he said. “This project wasn’t merely about finding a suitable home for the Beth Israel congregation, but continues to invoke national Jewish themes…. Certainly in Berkeley, we believe in ‘think globally, act locally,’ but it needn’t be an either-or proposition.”

Outside events also played a role in hurting fundraising. Nearby Silicon Valley was walloped by the dot-com bust as the congregation’s fundraising efforts were cranking into high gear. Then came September 11, a plummeting stock market and rumors of war. Donors who were previously unstinting have tightened their belts.

“The economy certainly contributed, and in addition, there are a lot of building projects underway, if you look at the entire Bay Area,” Resnikoff said. “People are tapped out.”

Plans for a new 27-acre Jewish community campus between San Francisco and San Jose had to be broken into three phases due to sluggish contributions in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks. The next phase will take another five years to finish, and the project is not expected to be completed before 2015.

Bitter disagreements over money and direction prompted the Judah L. Magnes Museum of Berkeley and the Jewish Museum San Francisco this month to dissolve a year-old alliance that coordinated their fundraising efforts. The Jewish Museum has raised just $37 million for a new downtown home, designed by Daniel Libeskind, originally budgeted at $100 million. The Magnes Museum has been unable to secure $46 million in pledges for a new museum in Berkeley. Both institutions have let staff go.

Although the Berkeley congregation was unable to recreate the Przedborz synagogue, another congregation just might succeed. Silverman, Beth Israel’s rabbi, said he’s been contacted by a Northeast synagogue he declined to name that is “definitely interested in incorporating elements” of the Polish synagogue into its construction.

Wittman, an architect, said he would gladly make the plans available. Despite the apparent death knell of the wooden synagogue project, he clings to the hope that a benefactor will provide $1.5 million and reinvigorate the Berkeley project at the last minute.

That patron better not tarry. Beth Israel expects to break ground for its new building in October.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.