Billy Rose Was Showman, Patriot — and Zionist Hero

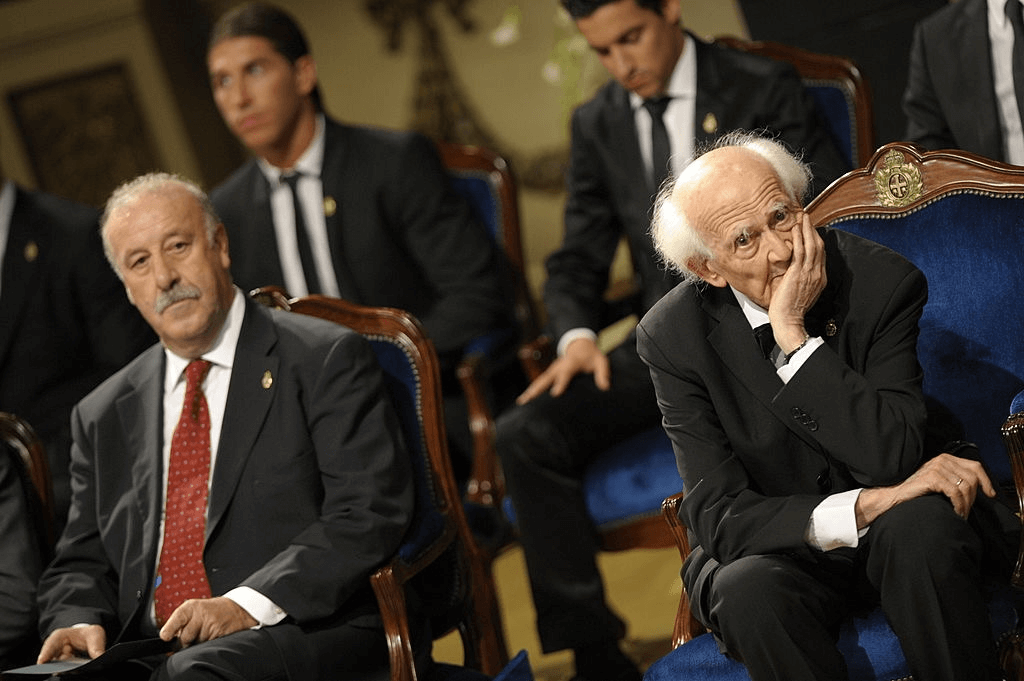

The Patriot: Billy Rose with David Ben Gurion. Image by Wikimedia Commons

On August 3, 1964, Billy Rose suspected that Teddy Kollek, the future mayor of Jerusalem then working in the Israeli prime minister’s office, was harming his shot at immortality. Rose was furious. His plan for a sculpture garden at the Israel Museum, which turned 50 on May 11, was not just another chance for fame.

Rose knew about fame. Over the past 35 years three movie studios had paid for the rights to his name and life story, and three publishers tried to produce his biography. He had starred on his own television show, written a best-selling memoir, produced a syndicated column that ran in 300 newspapers in 38 countries, attached his name to some of the most popular entertainments of the mid-20th century, married first one of the most famous women in America and next one of the most beautiful, and was steady copy for the scores of columnists, newspapers and magazines that wrote about Rose the songwriter, nightclub owner, theatrical producer, impresario of spectaculars, art collector, stock market investor and multimillionaire.

All of that now seemed like small potatoes compared to his opportunity in Jerusalem. There, at the heart of the young state of Israel, on a hilltop overlooking ancient vistas, were five acres that would forever be called the Billy Rose Art Garden. After years of planning and construction and much money, this pristine parcel would complete Rose’s journey toward the American Jewish identity he had wrestled with his whole life. That identity required a spectacular Jewish achievement. All his American projects were oversized and gigantic, so a Jewish one had to be wonderful just to be noticed, let alone achieve a balance between his passions for both. The Art Garden was it. As part of the new Israel Museum it offered him permanent remembrance just as his American projects were fading from the scene. The timing was also perfect in another way. The garden would open on May 11, 1965, and Rose would die less than a year later, at age 66. And now Kollek seemed to put his project at risk. Were planned buildings going to block the views from Rose’s art garden?

“What in the name of Christ does this mean,” Rose demanded in his August 3 letter to Kollek. He had a talent for the inappropriate.

Kollek’s reply on August 11 reassured Rose. “We shall still have the nicest Museum Hill in the world, the most suitable and the most unspoiled site that anybody anywhere can imagine in the centre of any capital city in modern times.”

Those were the kind of superlatives Rose had built his life on, and nothing less would do for this last Billy Rose production. He would get the legacy he wanted.

Helene Schwarz would have told him not to bother. As far as she was concerned, what Rose had done 25 years before was so selfless and generous it absolved him forever of any need for worldly fame and honor. “Dearest Mr. Rose,” began her 1939 letter from Vienna. “If ever in your life you have a special inner wish that calls for fulfillment, think of the mother who prayed for her beloved son every day and included in this prayer the one who saved her child.”

This note had to be kept secret. Rose was known as a hardboiled tough guy and a letter of moving gratitude from a Jewish mother in Nazi Europe would ruin everything. A Broadway producer with a heart of gold was as sappy as it gets. So Rose never told anyone — not his friends, sisters, or any of his four wives — about how he saved the life of Helene Schwarz’s son.

•

On February 8, 1938, Kurt Schwarz quit his job as a clerk at Vienna’s grand Hotel Bristol, said goodbye to his mother, and fled to Rome. It was a smart move. One month later the Nazis invaded Austria. But the 21-year-old’s escape did not protect him long. In May 1938 Adolf Hitler made a state visit to fascist Italy and under German influence the country ended its role as a safe haven for foreign Jews. The refugees now had until March 12, 1939, to leave the country. This was a crisis. There were few places Jews could go and many unable to find refuge by that date were literally pushed across adjacent borders and left stranded and penniless in France, Yugoslavia, and other countries. Schwarz appeared to be trapped. Then on March 4, 1939, just a week before the deadline, his mother learned he had obtained a visa for North America. Schwarz had also found the money to pay his passage. “He’s going to Cuba,” exclaimed his cousin Gerta, who read Schwarz’s letter to his mother. “He’s leaving, thank God.”

The other party that deserved thanks was in a New York penthouse apartment thinking about beautiful girls. Billy Rose was not goofing off. Business required it. His Billy Rose’s Aquacade – a synchronized swimming spectacle featuring a 40-piece orchestra and 200 Aquabelles in bathing suits – was due to open in April at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. It would top anything he had ever done, which was a lot. His nightclubs were the most successful in New York, and over the previous 10 years he had graduated from obscurity to fame to being practically unavoidable.

The whole country was familiar with Rose’s formula, and that was simply to name his every effort after himself. Since 1929, in an effort to escape the considerable shadow of Fanny Brice, the famous actress and singer he married that year, New York had seen Billy Rose’s Music Hall, Billy Rose’s Casa Manana, Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe and Billy Rose’s “Jumbo,” a circus-cum-musical featuring trapeze artists, lions and lion tamers, music and lyrics by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, as well as Jimmy Durante’s head under the foot of an elephant.

Rose also colonized territories west of the Hudson. In 1936 he produced the “Frontier Centennial” for Fort Worth, Texas, which was determined to upstage neighboring Dallas on their state’s 100thth birthday, and in 1937 he invented Billy Rose’s Aquacade for Cleveland’s Great Lakes Exposition. Rose seemed to be everywhere, and those he could not entertain directly he thrilled virtually.

With the help of the best publicity men in the business and his restless ability to create glitzy, garish spectacles, reporters delighted in covering the Billy Rose beat. Press coverage was an essential Rose nutrient. The health of his image depended on it. The whopper Rose told about how his ascent began as a teenager when he won a shorthand contest despite a wounded hand was a yarn his contemporaries relished. It was part of the up-from-the-slums success story that made him a hero to a generation of Americans. Philip Roth’s Alexander Portnoy suffered through Rose stories as his Depression-era father begged to him follow in the footsteps of this sharp dealer. “My father plagued me throughout high school to enroll in the shorthand course. ‘Alex, where would Billy Rose be today without his shorthand? Nowhere! So why do you fight me?’”

As the old saying goes, you can’t buy that kind of publicity. But you can encourage it, and Rose did. Syndicated columnists Walter Winchell, Leonard Lyons and Mark Hellinger, The New York Times and regional newspapers, the magazines Life, Look, Time, Newsweek, Saturday Evening Post, Vanity Fair, Fortune and more all competed with Rose’s publicity machine to crown him with monikers that captured the discrepancy between his outsized ambitions and his comically modest stature. The five-foot two-inch Rose was the Bonaparte of Broadway, Mighty Midget, Bantam Barnum. Some years later the renowned historian of Italian Renaissance art, Bernard Berenson, gave Rose the title that suited him best: “the quintessence of sheer cleverness.”

Still, as far as anyone knew, that cleverness did not apply itself to anything beyond beautiful girls and money. Rose always showcased the former to yield the latter.

But it was Rose who secretly rescued Kurt Schwarz. He was one of the many Jews so desperate to leave Europe they wrote letters begging the help of complete strangers. In April 1939, for example, two Jews in Vienna and Budapest wrote to the artist Al Hirschfeld, famous for his New York Times drawings, simply because they were also named Hirschfeld. Rose’s fame seems to have caught Schwarz’s attention. Rose’s first telegram to him is a reply to a letter now lost. “If you come to New York will definitely give you employment in one of my enterprises,” wrote Rose on December 6, 1938.

The noncommittal telegram was not promising, but Rose was already thinking about the Jewish refugee situation. A month later, in January 1939, he produced an “All-Refugee Revue” at his Casa Manana club, and on Schwarz’s behalf he soon played the hero in the kind of political and human drama that informed and frightened the pre-war audiences that saw Alfred Hitchcock’s “Foreign Correspondent.” Rose investigated escape routes through Italy and France and arranged international money transfers. In late February Rose telegrammed again to say, “Arranged everything. Contact American Express.” On March 16, 1939, Schwarz sailed from Naples to Havana. That same day, Helene Schwarz wrote Rose to thank him for saving her son’s life.

But contrary to Helene’s assurances, Rose’s Jewish ambitions were not satisfied by this rescue. Rose revealed the scale of those ambitions in 1938, when a newspaper asked him to name his favorite historical character. Rose chose Benjamin Disraeli because he got “a great deal of satisfaction out of being a Hebrew who commanded the respect of the whole world.”

The Billy Rose Art Garden at the Israel Museum gave Rose the Jewish prominence he craved. In fact, he made sure it did. Rose announced the gift on January 6, 1960, at the annual dinner of the America Israel Cultural Foundation, held at New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel. He was not listed on the evening’s program. The guest of honor was film industry magnate Spyros Skouras, an important Christian friend of Israel. Rose, however, stole the show, and the next day’s news in The New York Times was about Rose, his million-dollar gift of sculpture, and his donation of the services of sculptor Isamu Noguchi to design the garden. An AP version of the story ran in papers across the country and Time Magazine devoted two double-spreads to photographs of the Rose sculptures destined for Israel, including works by Rodin, Daumier, Jacob Epstein and more. By March 1965, when Rose’s sculptures sat on the sidewalk outside his East 93rd Street mansion ready for shipment to Israel, his gift had grown from the original promise of about 50 pieces to more than 100.

“That garden is wonderful, it really is,” said its first director, Karl Katz, in a documentary about the Israel Museum. “It makes the museum breathe.”

In Jerusalem on the museum’s opening day, Billy Rose deployed his gift for showmanship to win the love of the Jewish people and have his Disraeli moment. At the city’s International Conference Center where crowds had gathered to hear dignitaries speak about the new attraction, Rose got on stage in dirty work clothes, explaining that he was still working on his art garden. This informal approach won over the Israeli audience, and after the applause died down he delivered perhaps his greatest line. Rose related that Ben Gurion asked him what should be done with the sculptures in case of war. Rose’s answer was, “Melt down my statues and make bullets.”

That kind of line still overshadows Rose’s genuine love of art, generosity to Israel, allegiance to the Jewish people, and rescue of Schwarz, which Saul Bellow fictionalized in his 1989 “The Bellarosa Connection.” Bellow learned of it from a friend of the deceased Schwarz. But the reviewers treated it as pure fiction, leaving Rose with his preferred reputation intact. “I’m in a racket,” he once told a columnist. “I’m not supposed to have any friends.”

Mark Cohen is writing a biography of Billy Rose for Brandeis University Press.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 2

Opinion I co-wrote Biden’s antisemitism strategy. Trump is making the threat worse

- 3

Opinion Stephen Miller’s cavalier cruelty misses the whole point of Passover

- 4

Film & TV How Marlene Dietrich saved me — or maybe my twin sister — and helped inspire me to become a lifelong activist

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture Jews thought Trump wanted to fight antisemitism. Why did he cut all of their grants?

-

Opinion Trump’s followers see a savior, but Jewish historians know a false messiah when they see one

-

Fast Forward Trump administration can deport Mahmoud Khalil for undermining U.S. foreign policy on antisemitism, judge rules

-

Opinion This Passover, let’s retire the word ‘Zionist’ once and for all

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.