Keith Sachs Would Rather Be Collecting Art in Philadelphia

Image by Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Clad in a glen plaid blazer and paisley tie, Keith Sachs, the white-haired Philadelphia art collector, pointed to a Dan Flavin sculpture from his collection. “The Diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Robert Rosenblum),” consists of a white fluorescent bulb installed diagonally on the wall. “He needed some money, because he was getting married at the time,” Sachs said. “So he sold us this.”

Here at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Sachs, the former CEO of the alcoholic-beverage packaging distributor Saxco International, pointed out works of other artists whom he and his wife Kathy Sachs, had befriended: Jasper Johns, Donald Judd, Joel Shapiro and Richard Tuttle. “Ad Reinhardt died before we began collecting,” he said, gesturing to “Red Painting” (1953). Elsewhere in the exhibit of about 100 works from the couple’s collection, many already gifted or promised to the museum, are letters and birthday cards that artists wrote to the collectors.

“I was a businessman,” Sachs said. “They have an entirely different take on life.”

Toward the end of the exhibition, “Embracing the Contemporary: The Keith L. and Katherine Sachs Collection,” Sachs paused in front of Howard Hodgkin’s painting “Keith and Kathy Sachs.” The colorful work, in which the paint spills over into the octagonal frame, reads like a portrait only insofar as there are two vertically oriented forms. The treatment is a symbolic rather than a literal depiction of the two collectors.

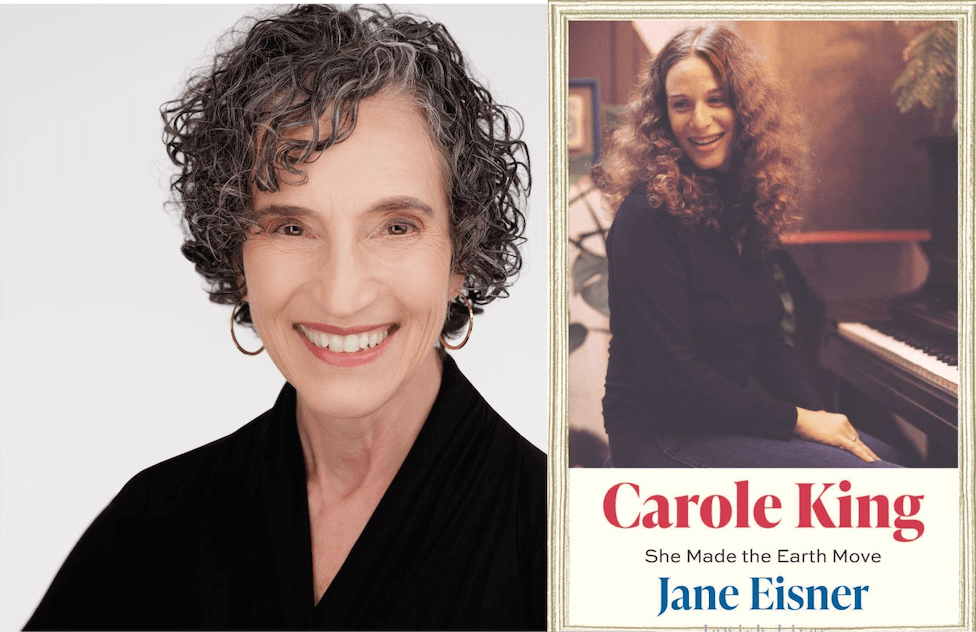

The Collector: Keith Sachs at the exhibition “Embracing the Contemporary: The Keith L. and Katherine Sachs Collection. Image by Menachem Wecker

“The only thing we knew was that he was doing a portrait of the two of us. We knew it wouldn’t be realistic, because that’s not the way he paints,” Sachs said. “It’s not what we expected. If it had been what we expected, we probably would have been disappointed.”

He commissioned the work in 1989 to mark the couple’s 20th anniversary. Hodgkin — who has referred to his aesthetic approach as painting about emotional situations — observed the collectors in London, Paris, Philadelphia and New York, but he did so without a sketchbook.

“He would look at us intensely,” Sachs said. “We would be at dinner for four — with him and his partner — and sometime along the way, he would say, ‘Would you please change places?’ so he could look at one of us more intently than the other.”

The night before the Sachses viewed the work for the first time in Hodgkin’s studio, the latter told them they didn’t have to purchase it if they didn’t like it. The following day, they so enjoyed what they saw that they hung it over the mantel in their Philadelphia house.

Walking through the exhibit with Sachs, an honorary president and former chairman of the American Friends of The Hebrew University, several works by Israeli artists leap out. Yael Bartana’s film “Inferno” (2013), which is based on a São Paulo church that was creating a replica of Solomon’s temple, represents a “staged ‘historical pre-enactment’ of the Third Temple’s ruin,” according to the catalog, and Ori Gersht’s photograph “Cells: Cell 04” (2013) responds to bullfighting in Andalusia. The exhibition catalog connects the latter to a series that Gersht created of “fleeting landscapes taken from a train running along the same tracks that had brought Jewish prisoners from Kraków, Poland, to the Auschwitz concentration camps.”

Sachs doesn’t consider his Jewish background to have had a major impact on his and his wife’s collecting. The two set out from the start to collect works of their time, he said.

“One of the first things we bought, interestingly enough, before we were even married, was a print by an Israeli artist whose name was Aryeh Rothman. It was abstract, and we bought it for my apartment at law school in Cambridge,” Sachs said. “And we have some photographs of the hills outside of Jerusalem. But we didn’t go out and collect Israeli art.” (Another work in the exhibit is Ellsworth Kelly’s 1952 “Study for ‘Gaza,’” which the artists described as “visualizing the landscape of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict, specifically imagining the Gaza Desert positioned in relation to the Red Sea,” according to the catalog.)

The couple had recently returned from Israel, where Sach’s brother had received an honorary fellowship. Although Sachs doesn’t consider his Israeli holdings a reflection of any sort of religious significance, he has been involved with Hebrew University for more than 50 years.

When his father died prematurely in 1968, Sachs and his brother chose to make a donation in his honor to the university, to which he had been a financial supporter. Sach’s father had become involved with The Hebrew University of Jerusalem upon the recommendation of his close friend Sam Rothberg, who “headed Israel bonds forever” and was a close friend of Golda Meir’s, Sachs said. So to honor their father, the two sons made an unsolicited contribution.

When the executive director of the American Friends of The Hebrew University in Philadelphia learned of the donation, he called Sachs and paid a visit to his office. “They weren’t used to getting unsolicited contributions,” Sachs said. “At this point, I’m 23 years old. He takes one look at me, and says: ‘We’d like to form a young leadership group in Philadelphia. Would you be interested?’” He was, and so he began a half-century relationship with the institution.

On trips to Israel, Sachs tends to stay at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, and he has visited the nearby Safrai Gallery. That reminds him of the then-Pucker Safrai Gallery on Boston’s Newbury Street, which he used to visit with his wife.

Those sorts of anecdotes, which seem to pour out at every turn of the exhibit, speak to the value of this particular collection. Where some collect what seems likely to be profitable, or what is fashionable, the Sachs collection, which is to be Philadelphia’s collection, is wrapped up in their personal lives. When they started dating, her graduation gift to him was an old print of the University of Pennsylvania, and when he went on to Harvard for law school, she bought him a print from the same series of his new school. For an engagement gift, she bought him another print. “We just went from there,” Sachs said.

Menachem Wecker writes about art for the Forward.