That Time I Was Mistaken For Son Of Sam

The arrest of David Berkowitz, aka Son of Sam Image by Getty Images

Back in 1977, New York City was gripped by a fear unlike any other I have witnessed, except, of course, during the aftermath of 9/11. It was a reign of terror that saw six people murdered and seven others wounded. Most of those who were attacked were young women. The conventional wisdom was that the killer was looking for ladies with long, dark hair, causing many women to cut their hair short.

The attacks began in 1975, but it wasn’t until the summer of 1976 that women started being shot to death, execution style. By then, we learned that the killer was leaving notes taunting the police that said he would murder again, and the content of those notes led him to be known as the Son of Sam.

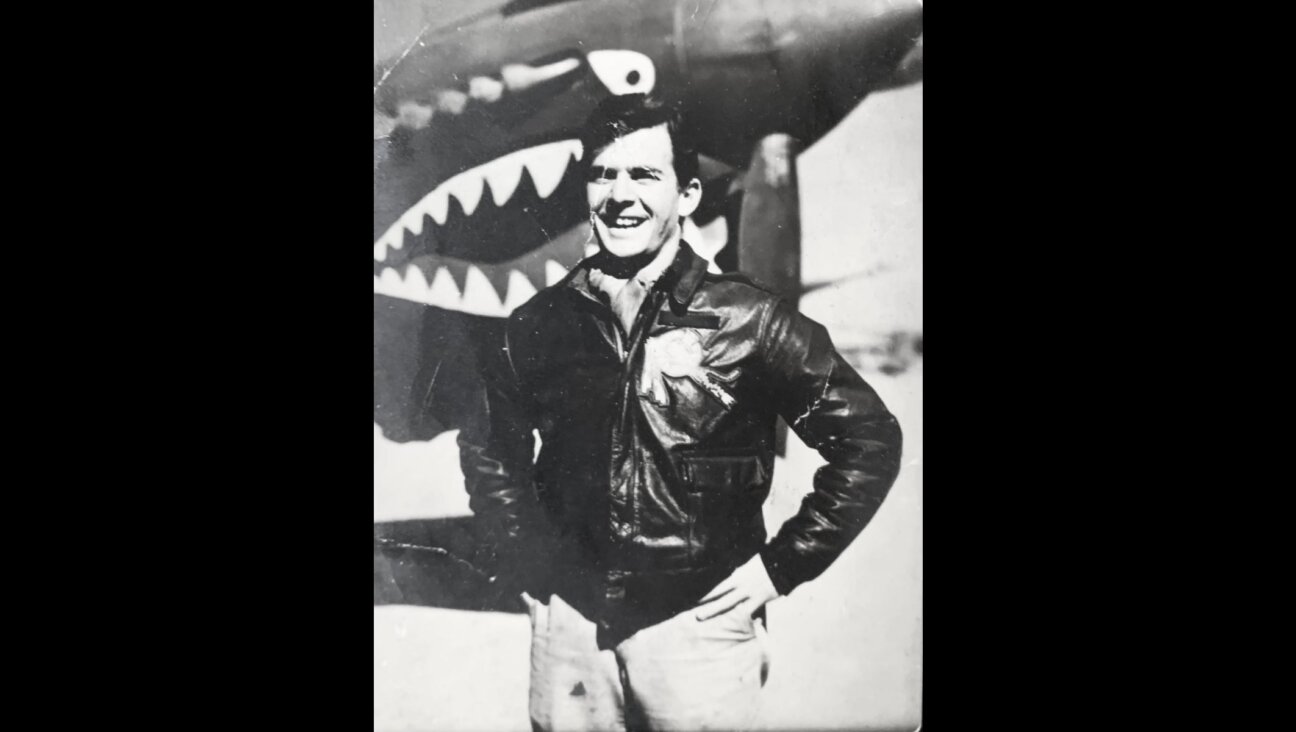

In the spring of 1977, the police brought me in for questioning. Someone had told the police that I had confessed to being the Son of Sam. The police had been following me for months and knew everything about my entire life. They took my photo to show to women in the Forest Hills section of Queens, where one woman had been killed. It was a few blocks away from where I lived.

This put a damper on my dating life, which wasn’t much, anyway; however, it also brought me a sort of perverse respect in the neighborhood, because it elevated me from nerd to possible killer. On August 10, the police finally caught the real killer, David Berkowitz. Even though he was now in custody, I remained a bit of a local celebrity.

Forty years later, my friends still enjoy bringing it up, especially when someone is with us who isn’t aware of my history. The truth is that I still enjoy telling people about it, too.

Every time, the reaction is either fascination or disbelief or a mixture of the two. People often smile, but sometimes the smiling is clearly mixed with a bit of uneasiness. Some will say, “They got the real guy, right?” Then they smile again, waiting for me to assure them that I am not the real Son of Sam.

Once I went out for drinks with a group of co-workers. I had been working with them for about a year. This group had been together a long time and they had no interest in welcoming newcomers.

They each told what to them were outrageous stories about themselves, and the group would laugh. When everyone had finished, I told my Son of Sam story. It was met with silence. I said goodnight and left, very pleased with myself. Eventually, some of them became friendly to me. I found it odd that was the story that loosened them up toward me.

Another time, I went on a dating site and met a lady. She suggested I meet her at a party the following night. I thought it an odd way to meet for the first time, but odd has never bothered me.

I showed up and about 20 people were there. However, there was no sign of her. It turned out to be a cult meeting. They played games at every meeting. In one of the games, a person would sit in the center of the room while the others asked him questions. You had to answer truthfully. At least that was the rule.

After a few people were questioned, I volunteered. No one knew me. One person asked me what could I tell them about myself that might shock the group. Of course, I told them of being questioned as a potential serial killer. They all tried to act cool and calm, but watching all of them strain into the backs of their seats was great fun.

When I was first brought in for questioning, the frightened and respectful reactions I got made me feel good, because I had never gotten that sort of feeling from anybody before. While most of the time when I tell the story, the mood is light and fun, sometimes I like recalling my feelings of being evil and dangerous, even though the reality is very far from it.

David Kempler is a New York-based film critic.