How This Neo-Nazi Came Out As Bisexual — And Jewish

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

In 1983, Kevin Wilshaw visited Dachau with three fellow neo-Nazis. He had traveled to Germany from England, his home country, and visited Hitler’s house and the Nuremberg Stadium in Munich with his German hosts. He asked them to take him to the nearby concentration camp. “They were very reluctant,” he said.

They took him, and the group stayed for about 45 minutes. “They didn’t really say much,” he said of the others. “I found it rather eerie, visiting a place where there’d been so much violence and death.”

What they didn’t know — and what no one else in his far-right community knew — was that Wilshaw has a Jewish heritage. For 44 years, he lived at least two lives. Openly, he was a neo-Nazi; in the closet, a part-Jewish bisexual.

Kevin Wilshaw in Germany, 1985. Swastikas are carved into the wall to the right of his friend. Image by HOPE not hate

The strain of keeping so many secrets weighed more and more heavily on Wilshaw, 58, until last month, when he decided he couldn’t deal with it anymore. He went public and renounced the far right. Now he feels guilty, and in part to atone is doing media interviews to try to fight the movement he once avidly supported.

He joined the far right in the 1970s as a teenager, and it formed the core of his adult life. That affiliation became his main source of identity and purpose, even as he kept key parts of himself hidden.

“I feel as if I’ve wasted my life,” he said, chuckling. He wore black clothes with white sneakers, and he sported a poppy pin on his lapel for Remembrance Day (similar to Veterans Day). He has short gray hair and a brown trimmed mustache, and he speaks with a regional accent from northwest England.

Hit With A Horsewhip

Wilshaw grew up in an environment where violence and suppression were commonplace and accepted. He was born in 1958 in the picturesque seaside village of Whitehaven, a former coalmining area that had become an industrial zone.

He was close to his mother, Patricia Wilshaw. Her maiden name was Benjamin, and her Jewish grandfather came from northern England. They didn’t know where his family emigrated from or when, but he spent 15 years working in South Africa before returning home and marrying Patricia Wilshaw’s grandmother. Kevin Wilshaw’s maternal grandparents did not practice Judaism or identify strongly as Jewish.

Wilshaw’s relationship with his father was tense. A local policeman, Jack Wilshaw was routinely violent and addicted to alcohol. He had grown up in a strict household in Cumbria and met his wife when they were working in Britain’s War Office, the government department then responsible for overseeing the military. When he worked as a horse guard, outside Buckingham Palace, he would sometimes be drunk on the job and urinate into his boots.

Jack Wilshaw would hit his three children with a horsewhip. One time he broke down the bathroom door to get at his son, who had locked himself in. But he left his wife alone “’cause he was scared of her,” Kevin Wilshaw said.

Growing up, Kevin Wilshaw knew almost no one with a minority background. His county of Cumbria — whose Lake District was immortalized in poems by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge — remains largely rural and ethnically homogeneous. He had one Chinese-British friend, whose parents ran the local Chinese restaurant. His father had a Jewish school friend, Joe Goldberg, who sometimes visited.

By the time Wilshaw became drawn to the far right, at age 15, he knew he had a Jewish grandparent. He also knew he was bisexual, and he had experienced the effects of being open about it. After coming out to a couple of friends, he got bullied at school. The violence stopped only when he changed schools, at 16, to prepare for university entrance exams. Though he didn’t go to university, he did three years of vocational training as a nurse.

But when it came to telling his family about his sexuality, Wilshaw said, “I kept it from them.”

When he joined the British Movement, an openly neo-Nazi organization, his family didn’t talk about that either — though he would get extremist literature in the mail, as well as visits from other extremists at home.

His parents were both Conservative Party supporters, with his father spouting racist and anti-immigrant views and his mother distrusting foreigners. His father tried, unsuccessfully, to stop his daughter from marrying a Pakistani-British Muslim man.

Yet they considered the far right too radical. So becoming an extremist, for Wilshaw, was a way to rebel against his father. When Jack Wilshaw tried to stop him from getting involved, he said, “I just ignored him.”

He acknowledged that if his father had tried reverse psychology, it might have worked. But in the end, his parents gave up.

Keeping Three Lives Apart

In addition to being exposed to racism and xenophobia at home, Wilshaw was able to access Nazi ideas in mainstream culture. He first watched Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film, “Triumph of the Will,” at age 14 on the BBC (with a disclaimer about its politics). “I was sort of hooked on it,” he said.

When he contacted the British Movement, a year later, he was seeking a sense of belonging and purpose. He was introverted, had few friends, and didn’t see other options for finding community or identity in his rural surroundings. The other activity he participated in was cross-country running — “a solitary sport.”

Kevin Wilshaw with the National Front, 1983. Image by HOPE not hate

“I thought [the far right] was the only way of actually busying myself and having something to fill my life with, which was obviously a wrong decision,” he said.

As he became more active in the far right — putting up posters and stickers, going to meetings and marches, writing letters to the press — he continued to hide parts of himself, but now with a new kind of family.

“I basically kept the three lives apart,” he said of his extremism, bisexuality and Jewish heritage. “One was in one compartment, one was in another, one was in another.”

He also suppressed a sense that what he was doing was wrong. Whenever that became difficult, he said, “I put it to the back of my mind, because I wanted to belong to these organizations. I sort of rationalized it, and then I sort of dismissed it.” As long as no one knew about his minority identities, he was safe and could fit in — or at least pass.

But when he came to London for far-right activities, he would visit gay clubs in secret, living moments of freedom and openness amid the repression.

“It was very liberating,” he said, “’cause you could actually let yourself go and be yourself, and not live a lie for a change.”

Wilshaw knew other extremists who, like him, were living contradictions: One of the bouncers at the gay clubs was a neo-Nazi acquaintance, and two London members of the National Front, a fascist political party, were Jews.

And his story puts some people in mind of Csanád Szegedi, a former leader of Hungary’s extremist right-wing Jobbik party who became a practicing Jew. Szegedi’s maternal grandmother survived Auschwitz.

In the 1990s, Wilshaw married a woman he met while working as a mental health nurse at a hospital. Over the years, in addition to working in nursing, he has worked in factories, most recently as a supervisor. The couple stayed married for three years, divorcing in 1995; they had a son together. Neither his wife nor their son ever approved of his extremism. He is still in touch with his ex-wife and sees his son regularly.

Around the same time, he was arrested and jailed for vandalizing a mosque in Aylesbury, 45 miles northwest of London. Aside from that incident, he said, he engaged in only “reciprocal violence” and never targeted anyone for his or her ethnicity, including Jews. He has not vandalized a synagogue.

But he accepted the violence, homophobia and anti-Semitism in the far right. He continued selling papers, going on marches and demonstrations, leafleting and writing letters to the press. He became a regional organizer for the National Front in Cumbria, and even ran as a parliamentary candidate for the party in 1989. He was involved with another fascist political party, the British National Party (which grew out of the NF), for 17 years. In recent years he spoke at meetings of the Racial Volunteer Force, a violent neo-Nazi group, though he didn’t become a member.

Along the way he has engaged in violence with several anti-fascist groups. He once smashed a chair over a man’s head at a local election in northern England, and in 1982 he was hospitalized after an altercation with the group Red Action.

Hope Not Hate?

The end of Wilshaw’s extremism began in 2015, when his mother died of dementia. Having stayed close to her, he called her death “a monumental event.” (His father had died five years earlier, of an alcohol-related illness, but Wilshaw said he and his father had been estranged and it didn’t affect him very much.)

The anti-fascist advocacy group Hope Not Hate noticed his behavior on social media grow more extreme. The organization, which is active in the United Kingdom and the United States, does community-based anti-extremism campaigns,; monitors, and reports on, the far right, and helps people leave the movement. Some of its staff are former extremists themselves.

Its head of research, Matthew Collins — an ex-extremist who has known Wilshaw from the far right since 1987 — said that in 2016, Wilshaw started posting about him “extensively” on Facebook. Wilshaw would write lengthy posts about Collins after he did media interviews, and once posted photographs of a child who Wilshaw claimed was Collins’s but actually wasn’t.

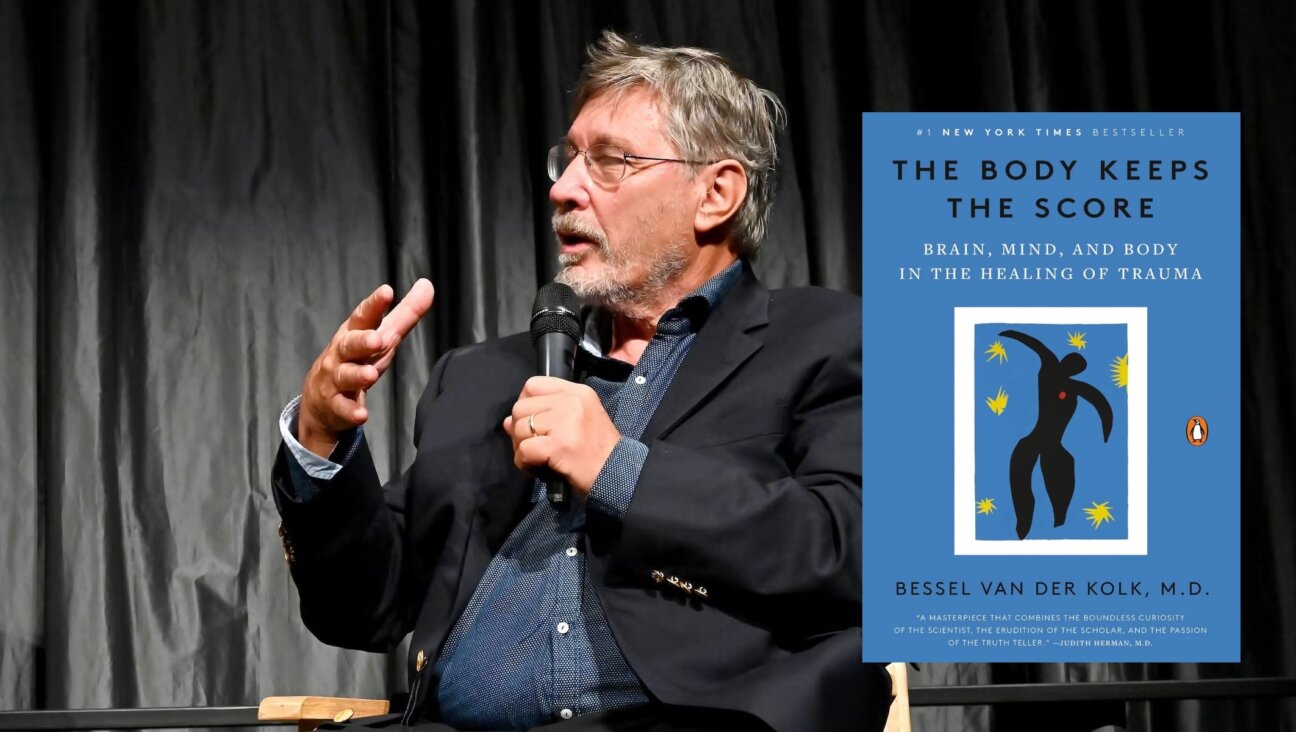

Matthew Collins, an ex-extremist who’s head of research for HOPE not hate. Image by HOPE not hate

Collins felt that Wilshaw was having a crisis. “I said, ‘Something’s not right with Kevin,’” he said.

Wilshaw agreed. “I just got more bitter and more extreme, and I thought, ‘I’ll take it out on the internet,’” he said.

Police in the U.K. monitor social media heavily, Collins said, so he wasn’t surprised when Wilshaw got arrested in March under the Malicious Communications Act, which makes it illegal to send or deliver communications designed to cause “distress or anxiety.” Since Wilshaw hasn’t been charged yet, it isn’t clear which communications he was arrested for specifically. He is on bail and has a court hearing in December.

After Wilshaw’s arrest, police referred him to Prevent, Britain’s deradicalization program. He asked to connect with Hope Not Hate, which he knew of from his decades in the far right.

Collins said, “I literally just waited for his phone call to come, and it came.” He asked Wilshaw what he wanted to do. One of the things Wilshaw suggested was to become an informant for Hope Not Hate. The organization has several “moles” working for it, who pass on information from within the far right.

Wilshaw had already been an informant once, providing information about the British Movement to the anti-fascist magazine Searchlight on one occasion in the 1990s.

But after working for Hope Not Hate for four months, he told Collins in July that he couldn’t continue. He found it too difficult to lie to his community about his commitment to the far right — while spying on them — and about his true identity.

Kevin Wilshaw, still marching in 2015. Image by HOPE not hate

“I said, ‘I want to sever this now and I want to go public with this,’” Wilshaw said. He wanted to bring attention to, and start mending, some of the damage that he and the movement had done.

Since leaving the far right and revealing his sexuality and heritage, most reactions have been supportive and congratulatory. He is in touch with a half-sister born to his father, who reached out recently.

He has had negative responses from the far left — not believing he’s finished with extremism — and the far right. He has cut ties with those connections completely but has read critical and abusive posts about himself in their online forums.

He also has some concerns about his safety. Hope Not Hate has offered him security, but so far he hasn’t felt the need to take that step. However, he and the group asked the Forward not to disclose the city or county in southeast England where he lives.

Last week he visited Highgate Synagogue, in London, and met a rabbi for the first time. He initially felt nervous and appreciated Rabbi Nicky Liss’s sense of humor. They toured the synagogue; Wilshaw said a prayer in English for his mother, and they had “a cup of tea and a chat.” Wilshaw said he’d like to learn more about Judaism.

Kevin Wilshaw’s 1984 membership card for the National Front, a British fascist party. Image by HOPE not hate

A journalist who interviewed him for Yediot Aharonot invited him to visit Israel, which he is considering.

Wilshaw said his life is “more positive now, more optimistic.” He plans to retire soon from his job as a factory supervisor and move back to Cumbria, his home.

But looking back on his decades of extremism, he said, “I could have done a lot more with my life than what I have done.”

He wants to “repair some of the damage” he caused by doing anti-racism work. After 44 years, he said he knows he has a lot of repairing to do. Collins would like to see him do educational outreach with Hope Not Hate.

“I would join an anti-racist organization, but a nonpolitical one,” Wilshaw said. “That sounds like a bit of a contradiction, doesn’t it?”