The Broken Guardrail of Democracy That Let Donald Trump Get This Far

Image by Getty Images

How did we get here? How did it happen that voters in the world’s greatest democracy are forced to choose a president from the two most disliked candidates since modern polling began?

Our question, how we got here, is actually two separate questions. For Democrats: Why is Hillary Clinton so disliked by so many Americans? And for Republicans: How did their party end up with Donald Trump?

The Trump question is the more consequential, given the stakes. It’s quite possible that America could be led come January by a president who’s prepared to abandon NATO, stifle the free press, default on the debt and give nuclear weapons to Japan, South Korea and Saudi Arabia. A man who admires dictators and casually demeans whole populations, yet rages over personal insults. A man who hates being told he’s wrong.

Not that Clinton’s unpopularity isn’t consequential. It matters, if only because it might put Trump in the White House. It’s the prospect of a Trump presidency, though, that has people around the world losing sleep. The real question for Democrats is how they chose a candidate who could actually lose to Trump.

Of the two questions, Trump is easier to explore. There are Republicans grappling frankly with the issue, asking hard questions in a reasonably objective manner. We can listen and learn.

The Clinton question is knottier. It’s discussed in two separate circles, neither one remotely objective: Clinton partisans and Clinton haters. The partisans are certain that her unpopularity is all due to outside causes — sexism, right-wing lies, media hostility, voter ignorance. These may play a role, but they don’t tell the tale.

Remember, there are other accomplished women who don’t draw the kind of antipathy Clinton has aroused. And it’s not running for president or challenging male privilege that fuels Hillary-hate. This started years ago. What’s more, her score has fluctuated over time. Her favorable ratings topped 60% early in her husband’s first term, again during his impeachment crisis and yet again when she was secretary of state. Now she’s disliked by nearly the same percentage that liked her then. And antipathy grows as the campaign proceeds. The more folks hear, the less they like her. Why?

Other explanations come from haters. Their versions don’t hold water, either. Dishonest? She’s no more dishonest than your typical politician. Slippery? Her worldview has remained fairly consistent. Ultra-liberal? She’s actually a centrist Democrat. What’s really going on?

The point here isn’t to discredit her. It’s to identify and address a problem that could hand Trump the presidency. That’s urgent.

But how has Trump even gotten this close? For starters, look at the landscape. Rightist illiberalism is rising throughout the West, from France to Hungary to Israel. My colleague Jay Michaelson, in an important new essay published last week in these pages, suggests two main causes. First, the uneven economic benefits of “neoliberalism and globalization.” Second, a surge in “racism and nativism” — which in turn are fed by anxiety over migration, jihadist terror and, ahem, “the slow sunset of white supremacy.”

At home, we’re seeing a breakdown in some of democracy’s built-in safeguards. Neoconservative author David Frum, formerly a speechwriter for George W. Bush, writes in The Atlantic of “The Seven Broken Guardrails of Democracy” that have allowed Trump to flourish. It’s a scathing indictment of his own party.

He lists the guardrails “from least to most alarming.” First, modesty in leaders’ public demeanor. Enough said. Second, trustworthiness. “Political scientists estimate that presidents keep about three-quarters of their campaign promises,” or at least try to. Outright lying is rare. Trump lies constantly. Voters see through it, yet back him anyway. They believe all politicians lie.

Here Frum is tripped up by party loyalty. Voters wrongly believe all politicians lie, he explains, because they’ve been promised balanced budgets for decades, along with lower taxes, a strong military and efficient government, and the politicians don’t deliver. But those weren’t lies, Frum cautions. They were “demands” from “the base” that GOP leaders promised even though they knew they were impossible.

Alas, those weren’t demands from the base. They’ve been core GOP ideology since Ronald Reagan. If Republican leaders knew they were impossible, then they’ve been lying for decades. If, more likely, they believed in these things, then they’re a band of fools. It’s hard to know which is worse.

Frum’s third guardrail is familiarity with public affairs. Trump is profoundly uninterested in how things work. But that reflects a longstanding Republican mistrust of experts and politicians. They repeatedly elevate “manifestly unqualified people” like Sarah Palin and Michele Bachmann. They’ve “come to value willpower over intellect.”

Fourth, ideological consistency. Voters nowadays support leaders not because of what they’re for but because of whom they’re against. Fifth, appreciation for “the primacy of national security concerns.” Sixth, “belief in tolerance and non-discrimination for all Americans.”

Finally, Frum laments the hardening of partisanship. Voters split their tickets less and loathe the opposing party more. He quotes mainstream Republicans who’ve settled for Trump because they find a Democrat unthinkable. When the other party is so demonized that “any nominee of your party — literally no matter who — becomes a lesser evil,” then we’re in trouble. “The last of the guardrails is smashed.”

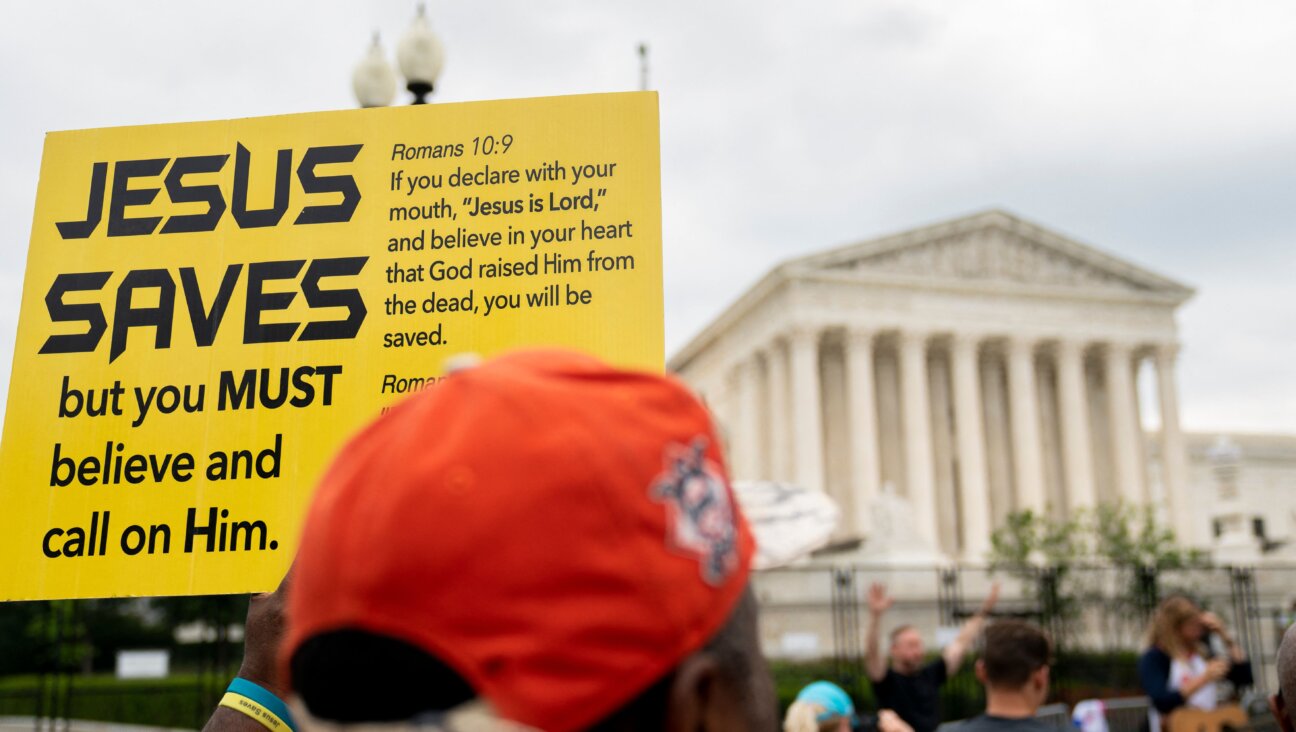

There’s one more critical guardrail that Frum fails to name: the voice of civil society, of mainstream American morality. It’s not enough to have minority activists chanting and venting their anger, confirming Trump’s supporters in their bigoted beliefs. What’s needed are the sober voices of the American majority. The churches, civic associations, unions — and, yes, synagogues and major Jewish organizations — that spoke out and marched for civil rights a half-century ago, that rallied against the Vietnam War, Soviet anti-Semitism and apartheid.

They’re all but silent now. And in their silence they send a message: that Trump is a legitimate contender to lead this nation. But he’s not. For all the reasons stated above, he’s a threat to the Republic.

Our civic leaders aren’t blind to the threat. Around the country, officials and activists in mainstream Jewish organizations are whispering anxiously, asking how their non-profit organizations can speak out against a political candidate — and how they can stay silent. They talk about their tax-exempt status, which forbids partisan political activity. They forget all the other divisive, even partisan causes that consumed them decades ago, to their everlasting pride. They ignore the relentless right-wing political activism of evangelical churches, under the IRS’s nose.

Mostly they pretend they don’t notice that it’s really pressure from a handful of right-wing major donors on every local and national board that keeps them silent, fearing to put donations at risk. The rightists have forgotten what it means to accept being outvoted, and liberals have forgotten what it means to stand up.

After this is over, they should all sit down and discuss what it means to run an organization and represent a community with values and traditions in a free society. Right now, though, we have an emergency.

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter @JJ_Goldberg

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO