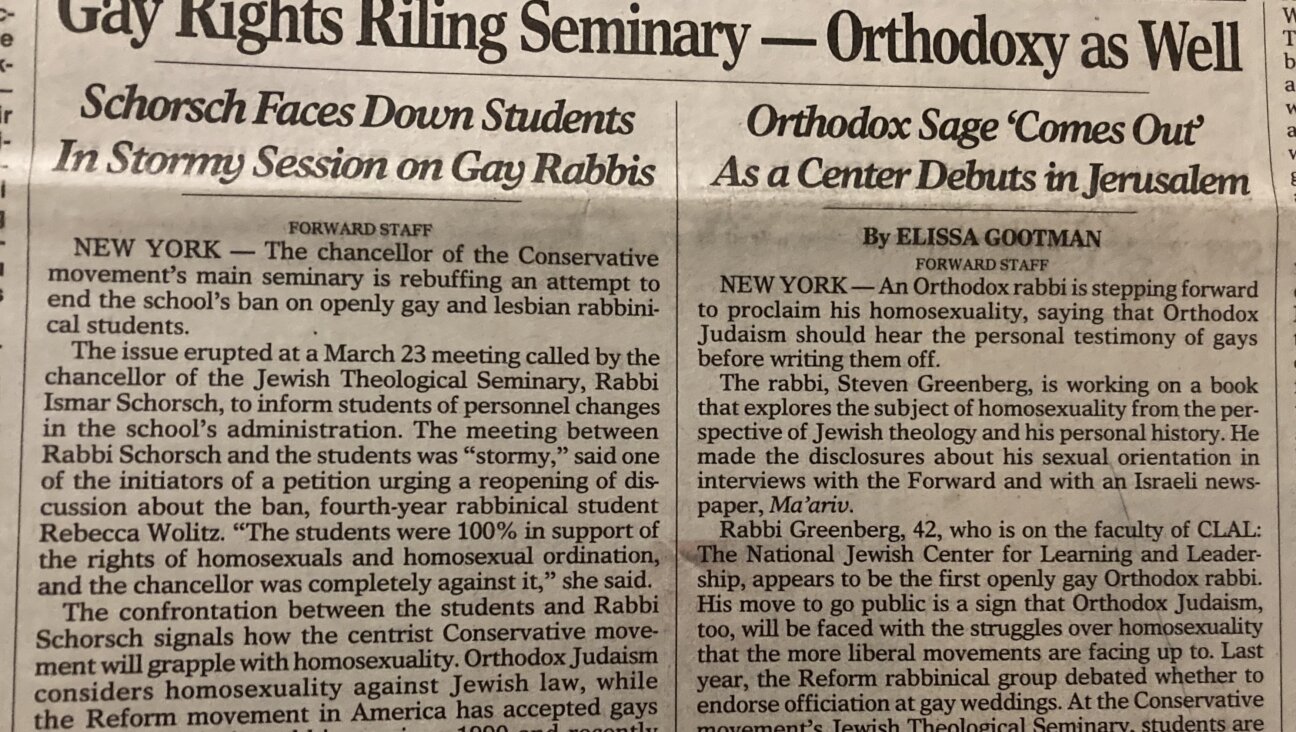

On the brink of a new Iran Deal, our Iran coverage through the decades

The task of illuminating the complexity of Jewish life in and in relation to Iran is one the Forward has always taken seriously.

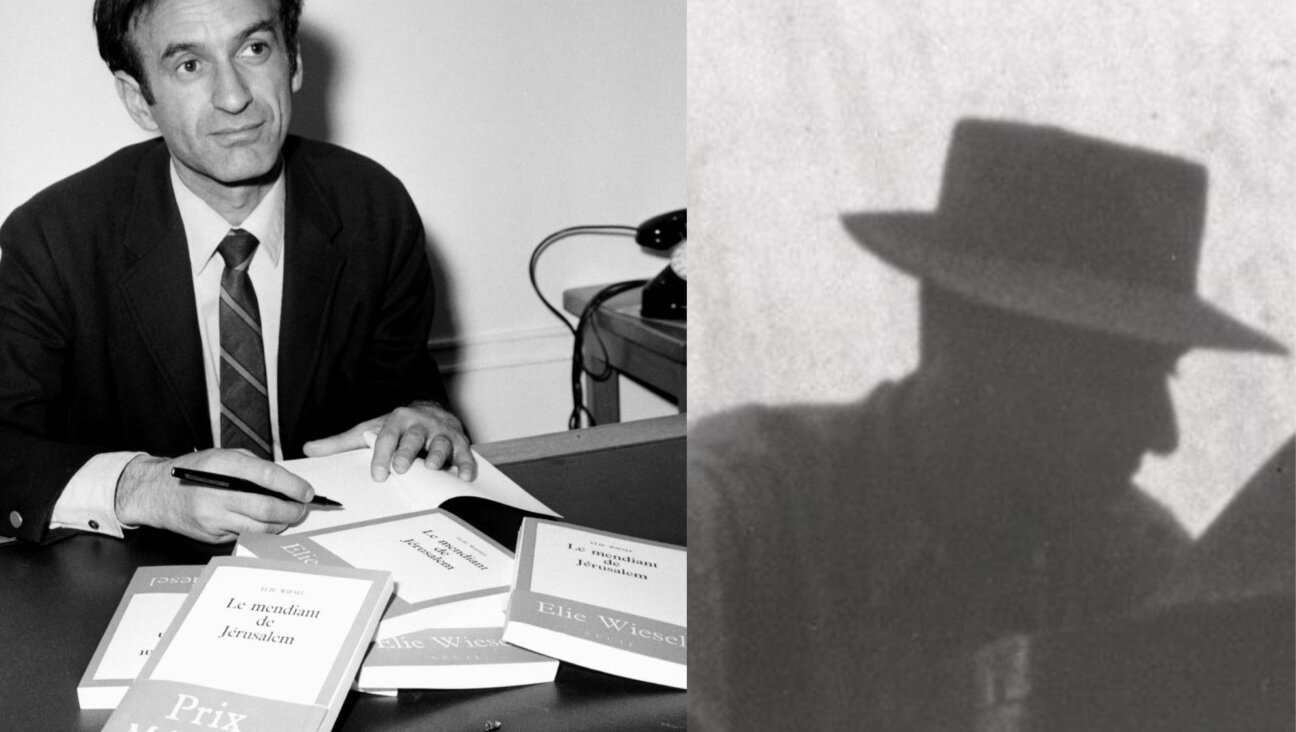

Ayatollah Khomeini’s tomb in Tehran, in 2015. Photo by Larry Cohler-Esses

To mark our 125th year, we’re revisiting some of the remarkable journalism our predecessors published. In this issue: Coverage of and from Iran, including one reporter’s intrepid journey there as the Iran nuclear deal came close to fruition in 2015. This article was originally published as a newsletter.

Read our first edition, about our coverage of a devastating 1930s famine in Ukraine, here.

It’s 2015 all over again, with the Biden administration trying to close an international deal to block Iran from developing nuclear weapons.

And just as when such a deal was signed under President Barack Obama — only to be revoked three years later by President Donald Trump — controversy over the ethics of engaging in diplomacy with the Iranian regime is widespread. Now, as in 2015, the American Jewish community is split over the negotiations, largely because of Israel’s vehement objections.

Back in 2015, shortly before the first deal was ratified, our Larry Cohler-Esses became the first journalist from a Jewish publication allowed into Iran since 1979, when the Iranian Revolution ended with the creation of an Islamic republic. Larry had lived in Iran for two years just before that revolution, as a recent college graduate teaching English in the cities of Shiraz and Ishtafan — a time that, he wrote, in many ways “constituted my real education.”

Getting a journalist visa took Larry two years, and an intervention by an Iranian Jew who had once served in the country’s parliament. During a week on the ground, accompanied by a government-chosen fixer, Larry found a country full of contradictions.

Iran’s small remaining Jewish community was subject to a host of discriminatory laws. But that community was also “broadly prosperous, largely middle-class,” he wrote, with members who “have no hesitation about walking down the streets of Tehran wearing yarmulkes.”

The government was oppressive, often brutally so. But, Larry wrote, “I was repeatedly struck by the willingness of Iranians to offer sharp, even withering criticisms of their government on the record, and their readiness sometimes even to be filmed doing so.”

Iran did not and does not recognize Israel as a legitimate state. Yet, “pressed as to whether it was Israel’s policies or its very existence to which they objected,” Larry reported, a number of government officials “were adamant: It’s Israel’s policies.”

Yousef Saanei, one of two Grand Ayatollahs he interviewed during the trip, dismissed as niche the idea that Israel should be destroyed: “What Israel should do is change its policies,” he said. “It’s impossible to destroy a country.” (On the other hand, Grand Ayatollah Abdolkarim Mousavi Ardebili said: “If the nature of the state does not allow for improvement, then the state must be destroyed.”)

Why send a Forward reporter to Iran in the first place? Jane Eisner, then the Forward’s editor-in-chief, explained her thinking in an editorial. “Iran remains chilling, hopeful, enigmatic,” she said. “Illuminating that complexity is our singular contribution to what has become a toxic conversation in too many quarters of the American Jewish community.”

As it turns out, the task of illuminating the complexity of Jewish life in and in relation to Iran is one the Forward had taken seriously for decades.

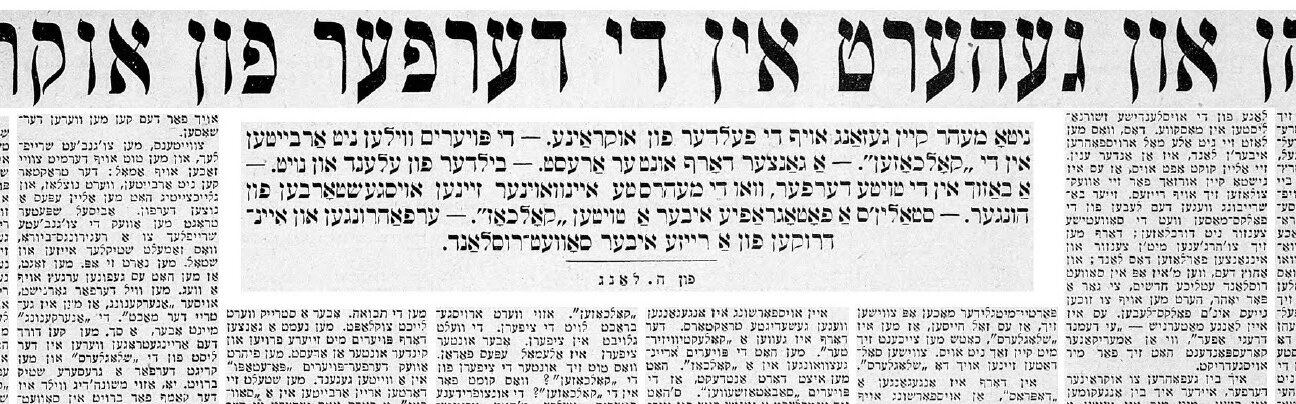

As a new nationalist movement gained traction in Iran in the 1940s, Nathaniel Zalowitz wrote a column headlined “The country is old and weak; Her king is young and weak.”

“It’s not looking good for the current dynasty in Iran,” he concluded. “England, on one side, doesn’t want Iran to have an independent existence and Russia, on the other side, has already gone at Iran. And she’ll take more and more of her. Once that would be called ‘capitalist imperialism.’ What should we call it now?”

Zalowitz’s scorn for the attitude of the international order toward interference in Iran was palpable; the very real question of what 20th century life might look like in a country that everyone appeared to want a piece of, equally so.

In 1959, an editorial by then-editor-in-chief Hillel Rogoff commented on an eerily familiar state of affairs. “The Soviet press and Soviet and Communist state radio stations unanimously bang away at it day and night,” he wrote, “that Iran’s future existence is endangered if she signs that defense agreement with the United States.”

And in 1979, amid a series of dispatches commenting with increasing alarm on the revolution, an editorial by Simon Weber articulated the Forward’s profound concerns about “the most reactionary religious Muslim leaders in the country” and “pro-Soviet ultra-left students” combining to proclaim “a revolt against the Shah.”

“That seems to be what’s uniting both groups of extremists. They have no positive program to suggest, and so far as is known, haven’t set one forth,” Weber wrote. “But that is also not the only thing uniting both groups. The Muslims inciters, and the pro-Soviet left students, are also poisoned with the toxoid of antisemitism and are filled with hatred of the Jewish state.”

The paper reported that year on the murder of Martin Berkovitch, a former colonel in the U.S. air force, who was working with an American firm in Iran’s copper industry. The second American to be murdered in the course of the revolution, “Berkovitch,” the Forward reported, “fell victim to his Jewish background.”

There were also articles about the end of Iran’s diplomatic relationship with Israel, which had never been formalized, as well as the trade relationship that, at that point, provided the young Jewish state with some 60% of its oil supply.

And the Forward noted the welcome that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the revolution’s leader, gave to Yasser Arafat, leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the clear links both men drew between their two movements.

Through all that coverage was a sense of profound regret — that a place so meaningful to so many, including the close to 100,000 Jews who lived there before the revolution, could turn in such a direction.

The country Larry Cohler-Esses found in 2015 was a place defined by economic strife and a state apparatus capable of extreme violence. It was also a place of beauty, where a couple outlined to him their vision for a grove of trees planted in the desert in honor of human rights.

They aspired “to present the beautiful aspects” of the idea,” Larry recounted in our pages. “The ideal of friendship and universal connection, the positive and pleasant aspects.” Anything that stepped into trickier territory would be impossible.

“Today, anyhow,” Larry wrote in 2015.