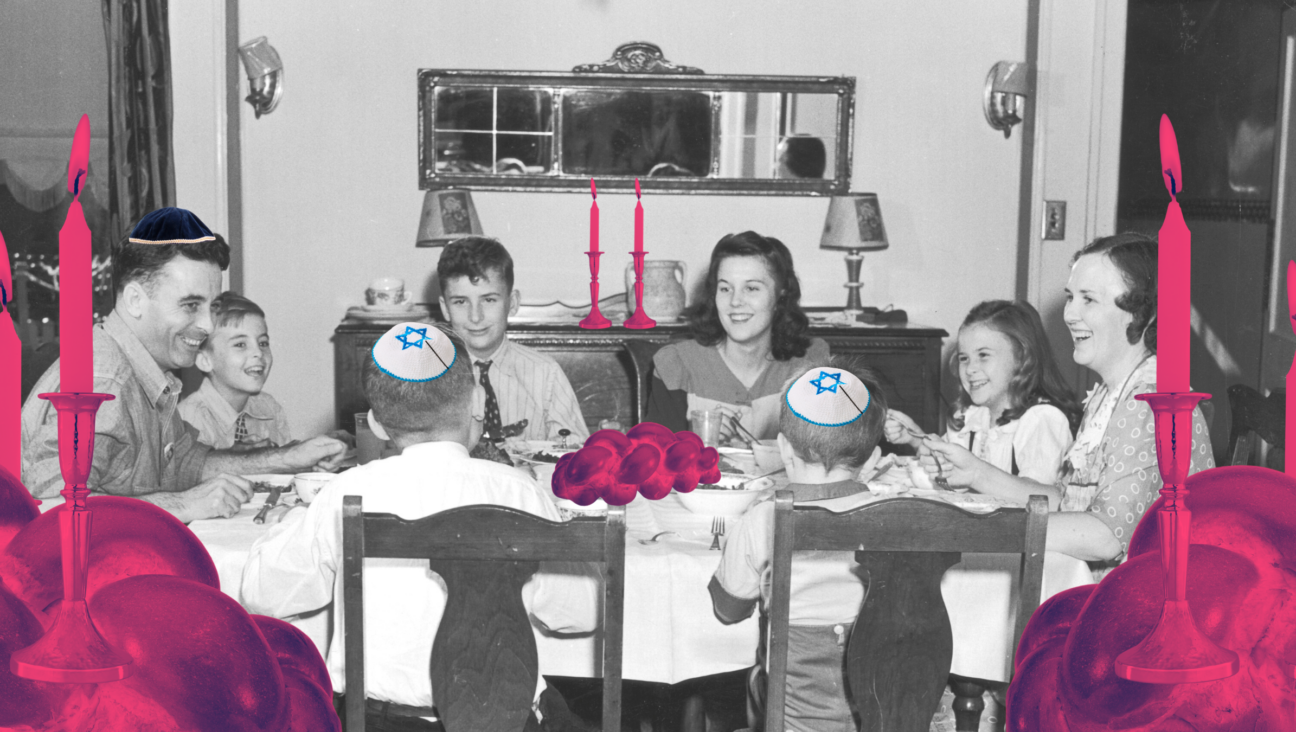

Can Orthodox Judaism Be Feminist?

Image by Getty Images

Feminist, to me, has never been a dirty word. In fact, as soon as I learned the word and its meaning, I embraced the term, cloaking myself in the righteousness of women’s rights, brandishing the banner of feminism as a challenge to those around me. When I was younger, I took on the childish causes that I understood to be of utmost feminist importance: my bat mitzvah thank-you cards were addressed to Mrs. and Mr., or Dr. and Mr. as the case would allow, but never Mr. first; I read fairy tales in which damsels rescued knights and women saved villages from angry dragons; I insisted that one day, I would propose to my husband, for certainly that would make a statement as feminist as burning a bra, only without the messy cleanup.

My understanding of feminism has become slightly more nuanced with age and experience, but I remain proud to call myself a feminist. My husband did propose, in the end, but our wedding thank-you cards were addressed to female partners first. After all, I would explain to those who rejected the f-word, to be a feminist is as simple as believing that women deserve equal rights as men. Sure, the word comes laden down with some baggage, but if you set the politics aside, it doesn’t take much to earn the label.

With all of this nestled comfortably among the other facets of my identity, I attended the ninth international conference of the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, or JOFA. It was my first time attending a JOFA conference, and I wasn’t sure what to expect, but I knew I wanted to be a part of the conversations going on that day. From sexual abuse in Orthodox institutions to the halachic and social implications of transitioning in the Orthodox community, the sessions were thought-provoking, inspiring, all those trite adjectives that will never fully capture the feeling I left with at the end of the day: the feeling of camaraderie and awe of spending a day among progressive, Orthodox social justice advocates; the feeling that my community was something to be proud of, that there were leaders and activists who were enacting change and fostering important conversations; the feeling that there was so much to be done, and so much that I myself could do.

But I also left with new questions. Not just about Orthodoxy or feminism, but about how those two categories interacted, and how they applied to me. I could easily call myself a feminist when it came to social justice issues. I have a Planned Parenthood bumper sticker on my car. I voted for Hillary. I work with survivors of sexual violence, and when I attended the session on sexual abuse in the Orthodox community, I felt strongly the pure passion that drove me to this career. I volunteer with Jewish queer youth (incidentally, at an organization called Jewish Queer Youth, or JQY) and when I attended the session about transgender individuals in the Orthodox community, I felt proud that such a conversation was even being held, excited that there were others who felt as strongly about inclusivity as I do. But am I an Orthodox feminist? I’m Orthodox, sure, and I’m a feminist, but when those terms come up against each other, do they clash? Can I honestly say that I’m feminist about Orthodoxy? Or, perhaps even more poignantly, am I Orthodox about feminism?

Fighting for equal rights in the religious sphere has never concerned me much. Getting an aliyah (turn to read from the Torah in synagogue) or wearing a tallit (prayer shawl) was not something that interested me personally, so I let other men and women occupy themselves with those issues. Because halachic Judaism never felt, to me, particularly oppressive—at least not specifically oppressive as a result of my gender—I never fought the Orthodox feminist fights. I recognized, of course, that halacha does not treat men and women equally. It would take an impressive amount of delusion to deny that. But it never bothered me. I chalked most of it up to the patriarchal society in which many of the rules of Judaism were decided. And while I’ve occasionally squirmed at the incongruence — hypocrisy, perhaps — of my secular feminism and halachic passivism, it wasn’t until the JOFA conference that I really paid it more than a passing thought.

One of the sessions I attended at the JOFA conference addressed the topic of kiddushin, or Jewish betrothal, and possible alternatives to the traditional marriage process. Kiddushin, as the speakers explained, is in actuality the legal process of a man acquiring a wife; in the Gemara, her acquisition is compared to the purchase of land. From a modern perspective, of course, this is sexist. Try telling a bride today that her marriage is an overpriced legal transaction wherein her husband is purchasing the right to have intercourse with her; this is far from the romantic ceremony of love and dedication that we have come to understand a wedding to be. The presenters, under this assumption of sexism, proposed a variety of ways to enact a halachic marriage without the inclusion of a one-way purchase. Sitting there, I thought back to my wedding day. It had never occurred to me to consider exploring the halachic aspects of our ceremony, let alone question or change them. Everyone I knew got married the same way that I had. Did this make me a fool? Complicit in a chauvinistic system? A self-hating woman?

If these thoughts were uncomfortable, they were nothing compared to my introspection about the parallel question: Am I Orthodox in my feminism? Many of my feminist beliefs—access to birth control; higher prosecution for sexual assailants—do not directly oppose halacha. But some of them do. Separating myself from my religious views, I have no qualms about standing up for a woman’s right to choose, and I believe that a woman should not be shamed for exploring her sexuality in whatever healthy ways she chooses. But this cognitive dissonance only gets me so far. Eventually, I must face that the halachic system I adhere to does have issues with many forms of abortion, that the laws of Judaism prohibit sexual activity between all but a heterosexual married couple. At what point do I acknowledge that I am advocating for issues that are, essentially, sins?

There are loopholes and logical roundabouts, of course. Perhaps I can say that I support a legal right for abortion, but as a halachically observant woman myself, would not make use of that right unless in the case of halachically-permitted situations. I can amend that I believe in healthy sexual exploration for women who are not Orthodox, while Orthodox women should explore within the confines of marriage. In other words, I can twist myself into knots to make myself more Orthodox about my feminism.

I can tell myself that I don’t advocate for change within the halachic system—that I’m not feminist about my Orthodoxy—because that is antithetical to how halacha works, but I don’t really believe that. I can assuage my feminist guilt by saying that I have priorities to my values, and halacha comes before feminism—and I believe that a little bit.

At the end of the day, however, none of these answers are intellectually honest. None of these excuses truly addresses that there are two distinct sides of me and that they stand in opposition to one another. That often, where they meet, they clash, and when they meld, it is more due to luck than any common principles.

I did not come away from the conference with any answers to these questions. I wonder how many other attendees that day think about the O as it relates to the F within the JOFA title, and whether they have come to satisfactory conclusions. Perhaps, though, this is what it means to be both Orthodox and a feminist. Perhaps it is to question and seek, but never fully find.