How ‘Shalom Aleykhem’ Originated and Why It Doesn’t Appear in the Bible

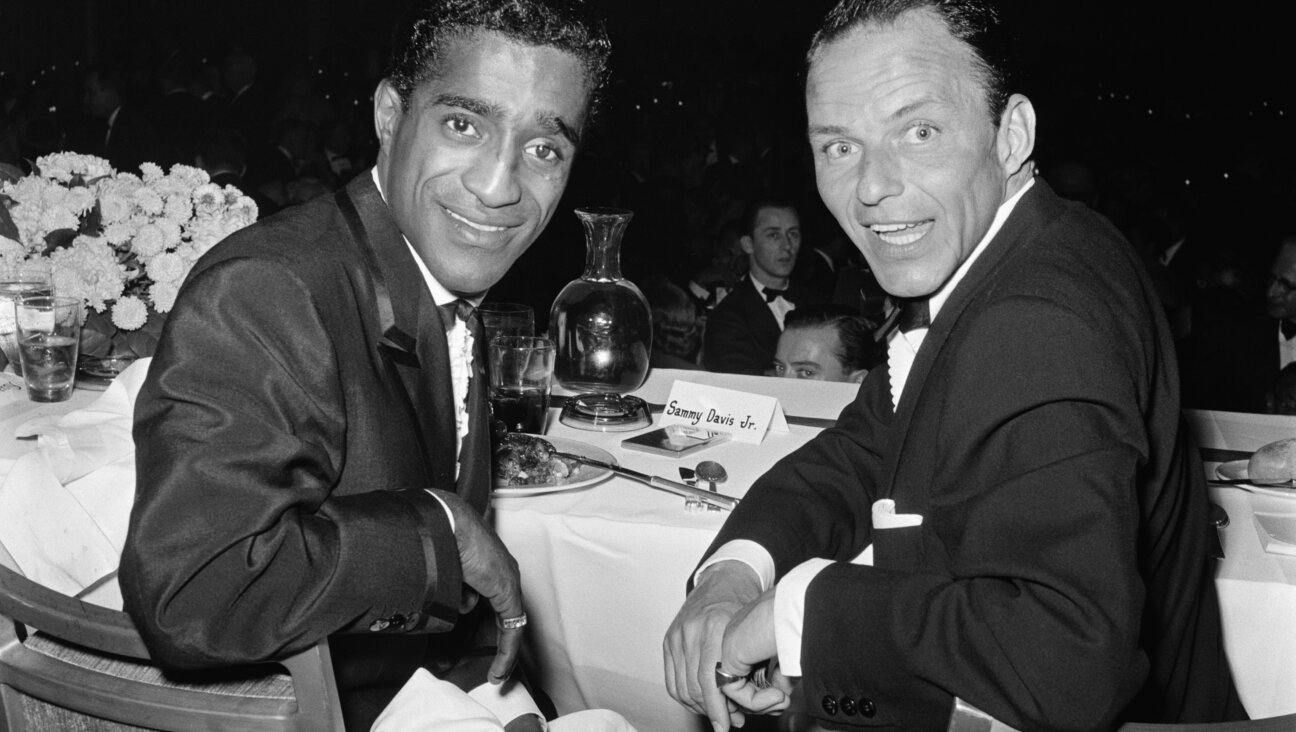

Shalom Aleykhem: The greeting is an ancient one, but in the Bible, the expression is simply shalom. Image by Forward Association

Samuel Sislen of Washington, D.C., writes:

“Jews have traditionally greeted one another ‘Shalom aleykhem’ and responded with the words inverted. Arabic speakers greet each other, ‘Salaam aleykum’ and also respond with the words reversed. And I have been told that some Christian services begin with the leader saying, ‘Peace be unto you,’ and the congregation responding, ‘And unto you.’ Where does this greeting originate and how did it spread?”

The greeting Mr. Sislen asks about is an ancient one. It does not, it is true, appear in the Bible. There, the expression is simply shalom, “peace,” or shalom lekha [“peace to you,” second-person masculine singular], shalom lakh [second-person feminine singular], etc. It seems to have originated in one of two ways.

One would have been as an assurance, when two people met, that the greeter had peaceful intentions; this is how it is used in several biblical passages, as in the story of Joseph, whose servant says to his frightened brothers, “Shalom lakhem,” i.e., “Don’t worry, you’ll be treated well.”

Or perhaps it started as a question, as in the story in Kings in which the prophet Elisha asks the Shunamite woman, “How are you? (“Ha-shalom lakh? “ — literally, “Is all well with you?”), and is answered “All is well” (“Shalom”). Besides meaning “peace,” the biblical shalom has the sense of “well-being,” and to this day the standard way of asking “How are you” in Hebrew is “Ma shlomkha?” – literally, “What is your well-being?”

In its form of shalom aleykhem, the greeting is first found in Hebrew in the early rabbinic period. By then, though, it was an everyday one. We know this from a comment in the Jerusalem Talmud on the Mishnaic tractate of Shevi’it, which deals with agricultural matters. In the Mishnah, the ruling is found that a Jew encountering a non-Jew farming the field next to his should always say hello “for the sake of good relations.”

How, the Talmud asks, should this be done? The answer is: “As one greets a fellow Jew, with a shalom aleykhem.”

Why the expression had aleykhem, with the plural form for “you” rather than alekha, the singular form, is difficult to say.

Perhaps this resulted from situations in which it was unclear whether one was addressing one or more people. In the New Testament, which is contemporary with early rabbinic Judaism, Jesus is quoted as telling his disciples, “And when ye come into a house, salute it. And if the house be worthy let your peace come upon it.”

What he is actually saying is, “When you enter a house, say ‘Shalom aleykhem’” — and indeed, when opening the door of someone’s home, one doesn’t know how many people are inside. Using a plural form would be natural then.

Shalom aleykhem, translated by the Greek New Testament as Eirene humin, and by the Latin New Testament as Pax vobis, was also Jesus’ way of greeting his disciples. The phrases entered both the Greek Orthodox and Catholic liturgies and is also used by the Episcopalian and Lutheran churches. In the Latin mass it is reserved, as Pax vobiscum, for the use of bishops; ordinary priests say “Dominus vobiscum” or “God be with you.” The congregation’s answer to a bishop is not, however, “Vobiscum pax,” but rather “Et cum spiritus tuo,” “And with thy spirit.”

An inverted answer, as Mr. Sislen point out, does take place in Arabic, where “Aleykum as-salaam,” “And upon you be peace,” is the standard reply to “Salaam aleykum.” It is possible, though by no means certain, that it was the inversion in Arabic — throughout the Middle Ages, the language spoken by most of the world’s Jews — that influenced a similar usage in Hebrew, for which there is no clear evidence in ancient times.

Yet the shalom aleykhem/salaam aleykum greeting in itself existed in both languages long before they came into significant contact and probably goes back to an ancient Semiticism that may have existed in other Middle Eastern languages as well.

In contemporary Arabic, salaam aleykum is not a greeting used for one’s everyday encounters (for those, there are more informal alternatives), and this is even truer of shalom aleykhem as it came to be used by Jews. In Yiddish-speaking Eastern Europe, it was an emphatic greeting generally reserved for either someone met for the first time or not seen for a long time, and it was not used with the family members, neighbors, friends or acquaintances seen on a regular basis.

Today, its use is even rarer, since among secular Israelis it is almost never heard at all. In both Israel and elsewhere, it is limited to Orthodox (although not necessarily Yiddish-speaking) Jews, and although a hearty “Shalom aleykhem” is still an expressive way of saying “Where have you been?” or “Pleased to meet you,” the average Jew can now go a lifetime without saying it or having it said to him.

Questions for Philologos may be sent to [email protected]