The Secret Jewish History of Muhammad Ali

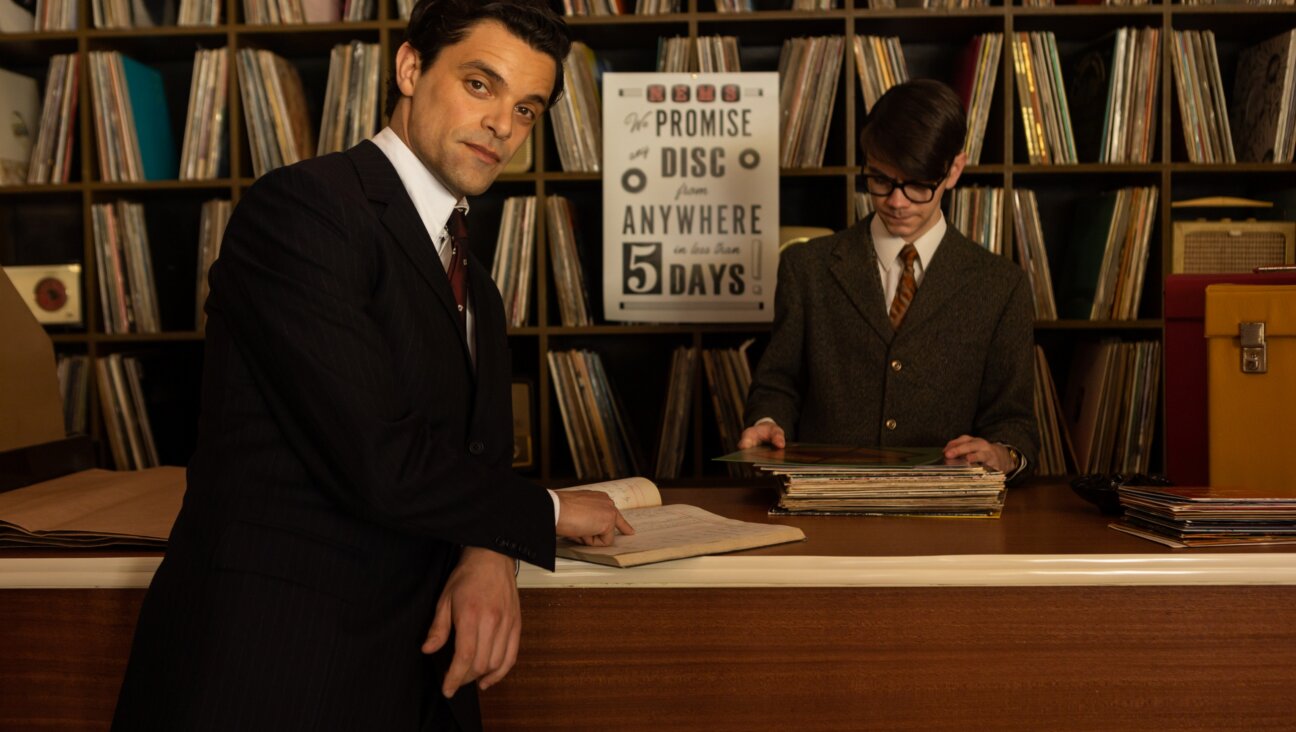

Image by Getty Images

The boxer Muhammad Ali, who died on June 3 at the age of 74, has been accused of having “frequently clashed with the Jewish people.” The truth is more complex. The Louisville-born heavyweight champ was raised a Baptist, but joined the Nation of Islam in 1964, abandoning his birth name of Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr. This discarded name was a noble one, previously belonging to a 19th century Kentucky planter who fought for slavery’s abolition. Ali’s decade-long adhesion to the radical Nation of Islam produced rote anti-Israel declarations. These parroted views did not just distress Jewish fans. Fellow boxing greats Joe Louis and Floyd Patterson disapproved as well. Patterson wrote in “Sports Illustrated” in 1964 that Ali had been “misled by the wrong people… He might as well have joined the Ku Klux Klan.” In 2013, his boxing promoter Bob Arum told “The Jewish Telegraph that he had to confer with Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam, before signing the boxer. Arum claimed that Elijah Muhammad was “never anti-Semitic towards me. He was anti-white for sure, but never anti-Semitic.” Ali himself eventually converted to a somewhat less extreme Sunni branch of Islam and later adopted a decidedly milder Sufism.

By the time of his 2004 memoir “The Soul of a Butterfly: Reflections on Life’s Journey”, Ali’s viewpoint was overtly ecumenical:

“Over the years my religion has changed and my spirituality has evolved. Religion and spirituality are very different, but people often confuse the two. Some things cannot be taught, but they can be awakened in the heart. Spirituality is recognizing the divine light that is within us all. It doesn’t belong to any particular religion; it belongs to everyone. We all have the same God, we just serve him differently…It doesn’t matter whether you’re a Muslim, a Christian, or a Jew. When you believe in God, you should believe that all people are part of one family. If you love God, you can’t love only some of his children.”

Crowning this new-won mellowness was Ali’s attendance in 2012 at his grandson Jacob Wertheimer’s bar mitzvah at Philadelphia’s Congregation Rodeph Shalom. At Rodeph Shalom, the oldest Ashkenazic synagogue in the Western Hemisphere, Ali “followed everything and looked at the Torah very closely,” told Ali’s biographer Thomas Hauser. The bar mitzvah boy’s father Spencer Wertheimer is Jewish, and identifying with that religion and culture, Jacob elected to participate in the ceremony. Of his grandson’s choice, Ali was “supportive in every way,” according to the boy’s mother.

Why should anyone be surprised? Ali’s devoted assistant trainer and cornerman Drew Bundini Brown (1928-1987) converted to Judaism after his 1950s Harlem marriage to Rhoda Palestine, of Russian Jewish origin. Brown was more than just a close friend and colleague of Ali’s; he actually wrote a number of the poems that Ali spouted to entertain audiences, attract ticket buyers, and intimidate opponents. Some Yiddishkeit might even be discerned in Ali’s interactions with the poet Marianne Moore before his 1967 bout with Ernie Terrell. As recounted in George Plimpton’s “Shadow Box,” the two poets met at Toots Shor’s Restaurant, where Ali assumed the role of yeshiva bocher with the rebbe Moore, writing a collaborative pre-match verse warning to Terrell. With typical humor, Ali could not resist poking fun at his wispy, fragile near-octogenarian guide by adding a final line: “After I am through with him he will not be able to challenge Mrs. Moore.”

Instead of such literary echoes, more often cited is the friendship between Ali and sportscaster Howard Cosell (born Cohen), whose daughter Jill told “USA Today” about Ali’s attendance at her father’s 1995 funeral: “[Ali] sat down next to me at my father’s memorial service. He could barely speak. After I read the family eulogy, Muhammad patted me. He had tears streaming down his face. I told him, ‘It’s OK, Muhammad.’” More than the bonhomie expressed in on-camera male bonding, the Ali-Cosell relationship was imbued with showmanship. Ali was clearly amused by Cosell’s unique vocal delivery, toupee, and penchant for alcohol. Cosell in turn was all show biz, as in his instruction to the cameraman, “Keep shooting,” when a celebrated pre-match squabble between Ali and Ernie Terrell degenerated into a donnybrook.

Cosell has been credited with readily using the name Muhammad Ali when more conservative sportscasters clung to his former name, a choice in which sheer delight at the sonorities of the more exotic and swaggering moniker may have played a role. Just as Ali himself relished pronouncing the middle name of Drew Bundini Brown — which often came out sounding like “Bodini” — Cosell’s delight in the spoken word, his only personal vehicle for feistiness, was evident. Both friends shared a joy in verbosity.

Ali’s overt affection for abrasive showbiz Jews was not limited to Cosell. In a 1963 episode of a chat show hosted by Jerry Lewis, Ali offered a flattering poem in honor of the actor Phil Foster (born Fivel Feldman), then doing a drunk act, followed by an ode to Lewis, which turned out to be sadly overoptimistic about the future:

“When [Lewis is] old and senile

He still will be funny

Laying folks in the aisle

Just as I will do Sonny [Liston].”

By contrast, the somewhat dated 1970s Billy Crystal impressions of Ali, in a tenor voice unlike Ali’s own elegant baritone, were awkwardly overlain with inapposite tones of servile African-American film comedians of the 1940s such as Willie Best and Mantan Moreland. Ali had the graciousness to laugh at this travesty when confronted by it at public occasions. Ali’s own voice, produced from the diaphragm like that of classical baritones, at times had sonorities reminiscent of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, or a charismatic chazzan. Rather than with Crystal’s strenuous spoofs, Jewish adoration of Ali is better documented by “King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero” by longtime New Yorker editor David Remnick and William Klein’s documentary “The Greatest” (1969).

Among his many other contributions, Ali will be remembered as someone who used poetry to express social justice and willingness to fight and die for a cause. In 1972 on RTÉ television in Ireland, he read a poem about the Attica Prison riot of the previous year. Although he would not be granted this conclusion to a grand life, the text is emblematic of his inner self:

“Better far from all I see

To die fightin’ to be free

What more fitting end could be.

Better surely than in some bed

Where in broken health I’m laid

Lingering until I’m dead.”

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.