‘Mein Kampf’ Is Back — And There Are Reasons To Worry About That

Image by Johannes Simon / Getty Images

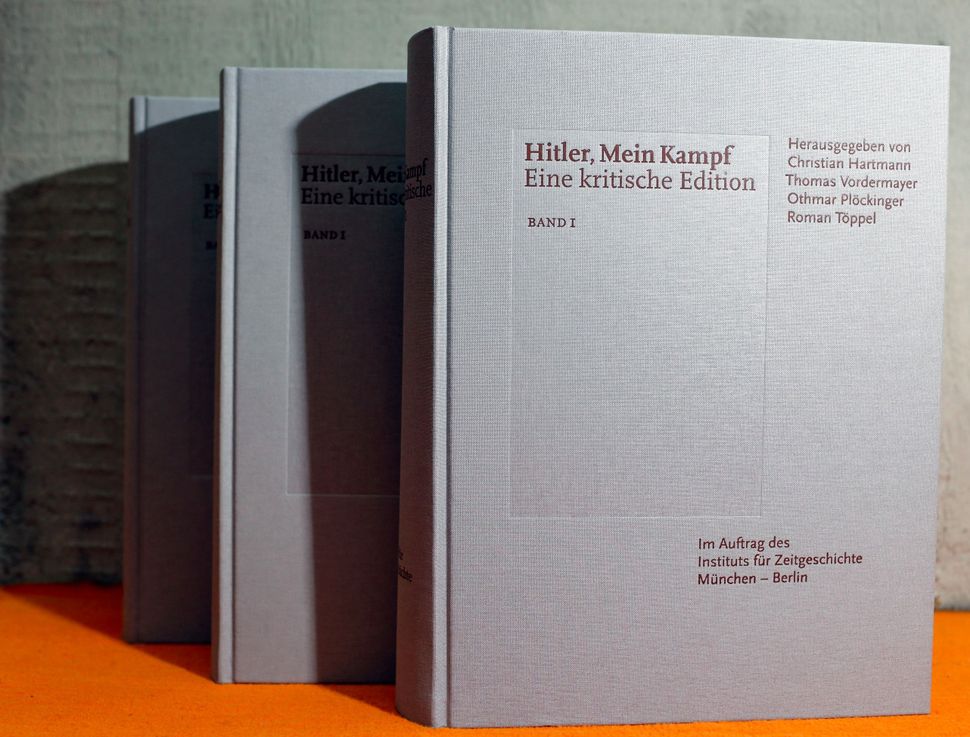

Yesterday, news broke that the new annotated version of Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” had become a non-fiction best seller in Germany with around 85,000 copies sold. The book had previously been banned from publication in the country (though it could still legally be read if a copy could be found). But in 2015, the copyright, owned by the State of Bavaria, lapsed, thus ending the state’s legal means of repressing new publications. The new critical edition, which includes commentary and contextualization from numerous scholars, comes in at two volumes and 1,948 pages (is there some kind of irony there?).

With the rise of far-right movements across Europe, many believed the republication of “Mein Kampf” to be a mistake – looking at the blatantly Nazi iconography of Greece’s Golden Dawn party, or the resurgent popularity of the swastika in Western Ukraine, it’s easy to see why. The fear is that the new publication will make Hitler’s propaganda more widely available, and therefore, more widely persuasive than if the book had stayed out of print. Those fears, however, after a year of publication, have gone unrealized.

As Deutsche Welle reports, the book’s publishers, The Institute for Contemporary History, “reviewed data collected by regional bookstores about the book’s buyers. The data showed that the book’s buyers tended to be ‘customers interested in politics and history as well as educators’ and not ‘reactionaries or right-wing radicals.’” It makes sense that an edition of “Mein Kampf” that costs $62 and strives to expose the lunacy of the text would be more popular with intellectuals than neo-Nazis and other far-right groups. The book, placed in critical context, can even be a new tool for scholars concerned with anti-Semitism – author Ben Cohen pointed out to Algemeiner, “For historians, for scholars of anti-Semitism, for those researching totalitarianism, it’s a key text in terms of establishing that Hitler’s war against the Jews was the foundation stone of the Third Reich.”

By all accounts, the republication appears to have been a success – sales and revenue for an important cultural institution, the decontextualization of a noxious book, and the addition of a critical tool for the teaching of anti-Semitism. There are, however, a couple reasons to worry.

First, as Loriene Roy, former president of the American Library Association, pointed out in an interview on NPR a few years back, banning books makes people more curious as to their contents. R.L. Stine, author of the beloved “Goosebumps” series, backs up Roy’s sentiment – “I’ve never noticed any kind of sales decrease because of these censorship campaigns. Usually they prove to be good publicity.” A ban is an invitation, not a deterrent. Now that “Mein Kampf” is back in the publication, headlines announcing its “overwhelming sales” add to the previously unavailable book’s mystique – to the uninformed, the question is not “how can we use this book to educate” but, “why exactly was it banned in the first place” (of course, almost everybody knows why “Mein Kampf” was banned, but many only know on a surface level without specific knowledge of its actual contents).

For the time being, the critical edition is the only reprint, but far-right publisher Schelm had previously announced plans to reprint “Mein Kampf” without annotation and without edits. (The plan, which faced legal scrutiny from German authorities, has yet to materialize). If, and when (it seems to be a matter of time), an unedited, unannotated edition does appear, the “forbidden fruit” appeal will be far more pernicious. Hitler’s writings, by virtue of renewed interest, could be made fresh again, that is, they could be debated abstracted from the history.

The second, and more worrisome, danger involves the book’s cover. The Institute of Contemporary History made the wise choice of publishing the book with an all white, sterile, academic looking cover. Not only is the book simply too large to use as a symbol (who wants to carry around a two volume set?), it is too boring, at least aesthetically.

Image by Sean Gallup / Getty Images

The book’s however, is quite captivating. (In a previous article I suggested reading Susan Sontag’s essay about Nazi aesthetics, “Fascinating Fascism” and I would like to once again stress its importance.) Red, black and white, the cover depicts a glaring Adolf Hitler with the title printed in that ominous, but alluringly Gothic, “fraktur” font (which, ironically, would be banned by the Nazis as “Jewish Letters”). The cover of the book, more than the contents, has the potential to be a powerful fascist symbol.

Paul Berman, writing for Tablet provides us with an analogy to Mao’s “Little Red Book:” “The Little Red Book was a fetish object. It was published on bible paper with a shiny plastic red cover, wallet-size, rather like the pocketbook street maps of Paris that used to be sold, except more stylish. Masses of people waved it in the air, as if it summarized the whole of human wisdom. I have noticed that, 50 years later, the plastic cover, shiny as ever, shows not the slightest sign of age.”

The fetishization of the book as an aesthetic object made it far more powerful than the writing – a cover can be waved about, it can be photographed and disseminated, it can be instantly assessed and absorbed by the viewer, it can take on a whole host of easily accessible semiological meanings that would take another book to unpack. If “Mein Kampf” is reprinted unabridged and with the original cover, it’s possible that we may see rallies in which the book plays a prominent part.

Despite these two fears, the critical edition, and the lapse of the copyright seem, to me, to be welcome developments. It’s a triumph of the free press that it can absorb even hate-speech and somehow transform it into something for the public good – the quickest way to defuse propagandistic fervor is to surround the propaganda with “3,700 footnotes.” That other, less beneficial publications may follow should not worry us too much – mystery, as we know, is a powerful attraction.

Jake Romm is the Forward’s culture intern. Contact him at [email protected]