The Last Time We Saw ‘God of Vengeance’ on Broadway, the Whole Cast Got Arrested

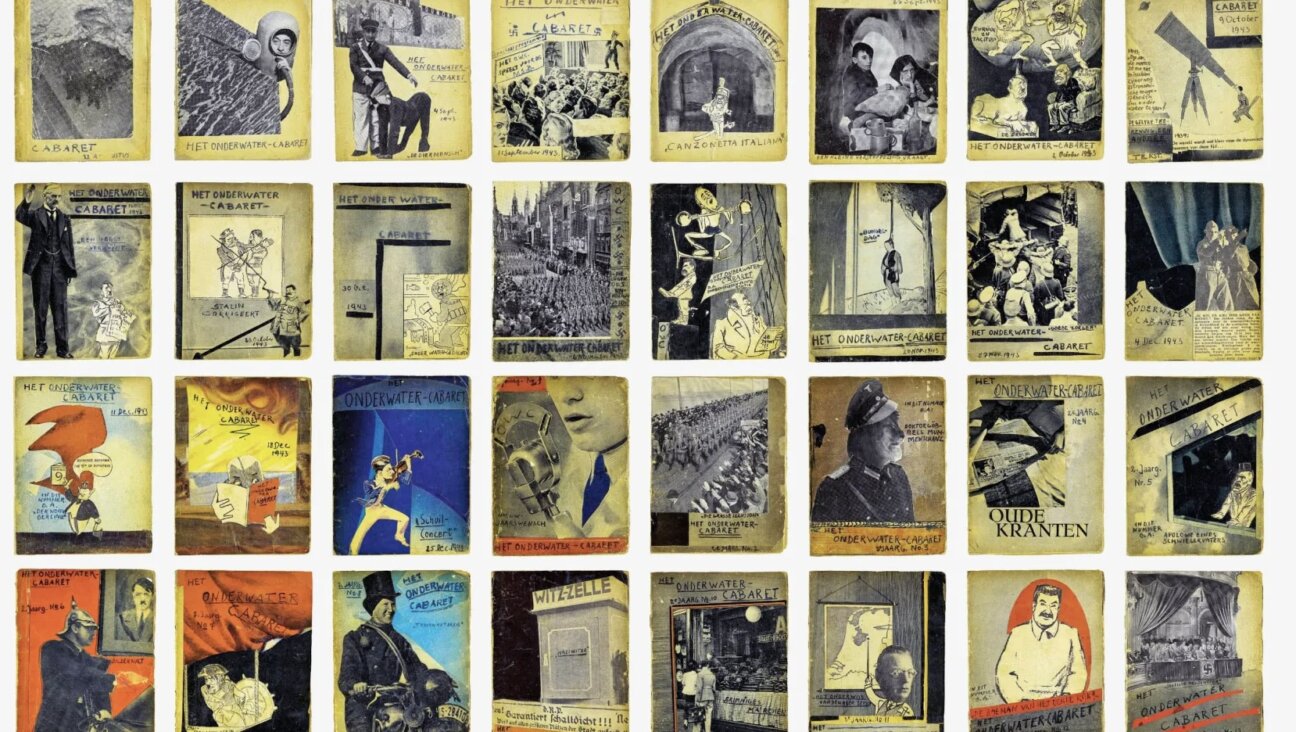

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

To Eleanor Reissa, director of New Yiddish Rep’s current revival of “God of Vengeance,” Sholem Asch’s controversial 1907 play is about questions, often maddeningly unanswerable ones.

“Who is to blame? What is it about? Who is the most corrupt? What does it mean to be this kind of religious Jew? What is a whore? What is a woman?” Reissa asked, speaking to the Forward over the phone.

And then, for a play originally written in Yiddish, in Poland, more than one hundred years ago, the kicker: “How does it resonate for people who look like us?”

That question got quite a bit of attention last spring, when Paula Vogel’s play “Indecent” premiered Off Broadway. Vogel dramatized the events surrounding the 1923 production of “God of Vengeance,” which featured the first lesbian kiss on Broadway, leading to the entire cast’s arrest and successful prosecution on charges of obscenity. “Indecent” proved successful and timely enough in its run at the Vineyard Theater to merit a Broadway production — it will open there in the spring.

For “God of Vengeance,” the challenges are different. “Indecent” acknowledged the troubled history surrounding its source text — the obscenity trial, the way Asch was ostracized from the American Jewish community, the fates of the play’s earliest actors and audiences who probably died in the Holocaust — and yet Vogel’s play emerges hopeful and iridescent.

A revival of Asch’s play can’t do any of that. The hero of “God of Vengeance,” Yankel Tchaptchovitch, is the inflexible and uncompassionate proprietor of a brothel. He tries to buy himself a better moral life by marrying his daughter Rifkele to a yeshiva student and commissioning a Torah, but unrepentantly flouts the principles that Torah is supposed to teach.

Similarly unredemptive is the play’s famed lesbian love story. The love between Rifkele, Tchaptchovitch’s coddled daughter, and her lover Manke, one of Yankl’s prostitutes, is, though unquestionably passionate, inherently unequal. When their affair ruins Rifkele, it’s hard not to believe Manke, who convinced her to run away to a competing brothel, in some way wanted her to fall.

Worst of all, perhaps, the Jewish community depicted in “God of Vengeance” exacts a cruel and petty price on those who fail to meet its standards. Those standards, although predicated on religiosity, are revealed to be morally bereft — they have less to do with the action of piety than its appearance. In one notable scene, the village rabbi Reb Eli informs Yankl that Rifkele’s indiscretions are meaningless; if he simply pays her would-be groom a higher dowry, it will be as if she never strayed.

Unlike “Indecent,” “God of Vengeance” won’t leave its audience feeling elevated. So, Reissa’s question — in 2016, how will this 1923 play resonate with a largely assimilated audience — yields no easy answer.

“It’s a moral play, it’s almost a passion play,” said David Mandelbaum, New Yiddish Rep’s artistic director, who plays the morally flexible Reb Eli. “It’s about atoning for sins through your children, and I think that’s something a lot of people will recognize.”

Beyond the (apparently everlasting) appeal of that theme, though, Mandelbaum sees the play as a reflection on the dissolution of ideals in a community, religious or otherwise, and that’s a topic of sharp contemporary relevance.

“God of Vengeance,” he said, is about “the idea of trying to buy your way to a state of grace. What we’re seeing in this country today, in the world, it’s kind of scary, in the same way that the resolution of ‘God of Vengeance’ is kind of scary, because what happens at the end? It’s a total collapse.”

Reissa, who also plays Yankl’s wife Sarah, agreed. She chose a modern setting for the play — in the last scene, Rifkele appears in a pair of trendy patterned leggings – partially to highlight how it speaks to today’s audience.

“It wasn’t that we were looking back at a time when people were greedy, that we were looking back on a time when religion wasn’t corrupt, when power wasn’t corrupt by money,” she said. “We live in that time still. A time of men brutalizing women – really, is that over? There’s corruption and falseness in the world we live in politically, and with religion.”

What still seems groundbreaking about “God of Vengeance” — and most difficult to translate — is the play’s suggestions as to the source of that corruption.

It’s easy to identify Yankl as the play’s villain, but he’s also the protagonist; it is, after all, a hallmark of the anti-hero that he creates his own downfall. Yet Yankl’s destructiveness both towards himself and, more painfully, his daughter, wife, and the prostitutes he employs often appears to be only the last gesture of a whip already in motion. He is a victim, albeit an unsympathetic one, of the classism and false piousness of his insular, rigid community. One of his crimes, and perhaps the greatest, in the eyes of the patriarchs with whom he consults, is his refusal to maintain the pretense of religiosity once it no longer serves a material good.

“God of Vengeance” requires its audience not to pardon Yankl, but to understand his shockingly irreligious actions as a response to the tyranny of his community’s perverse, hypocritical ideals. And yet the power behind those ideals is difficult to pinpoint; the characters — with one crucial exception — simultaneously propagate them and view them as externally imposed. What, then, is their source?

For an answer, look to the play’s title.

It’s no mistake that the only character who seems fully comfortable flouting his community’s religious norms is the one with, nominally, the closest connection to God — the rabbi. Asch isn’t proposing that God sometimes adopts a fearsome, vengeful guise; he’s suggesting that God, as heeded by humans, is vengeful and fearsome, and with a distinct lack of true moral purpose.

By making the audience’s pursuit of that line of logic all but inevitable, the play subjects its viewers to a relentless ethical violence, precluding the possibility not only of Yankl’s personal redemption, but also the redemption of his community and, by extension, his audience.

Asch’s heartwrenching deconstruction of ideological governance leaves the very idea of belief destabilized. No matter how noble the subject or practitioner, what good can fierce, single-minded faith do?

And so, at the end of the play, when — spoiler alert — Yankl sends Rifkele and Sarah down to the whorehouse to work there for the rest of their days, his gesture comes across as more than merely shocking. It is, in an odd way, the play’s only logical end. The loss of a god provokes retaliation; whether or not that retaliation is worse than actions professed to suit the god’s will is unclear.

And that’s the point — at least, in the world of the play.

“It’s damning to a kind of religious hypocritical community,” Reissa said. “I don’t mean all religion is hypocritical. But in this story, it is.”

Talya Zax is the Forward’s culture fellow. Contact her at [email protected]