The Secret Jewish History Of Theater’s Most Famous Skull

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Children are often told they can be anything they want when they grow up; they’re less commonly informed that the same rule applies when they die.

After all, the philosopher Jeremy Bentham requested that his body be embalmed and put to service as the mascot of University College London, where his physical remains still cheerfully preside (well, except when they’ve been stolen by the university’s rivals); contemporary moguls are having themselves cryogenically frozen so that, in a future they anticipate will involve extraordinary medical advances, they can be revived and cured of whatever it was that killed them; and André Tchaikowsky, a Polish pianist and composer who, dying of colon cancer in his 40s, requested his body be donated for medical science, but that his skull be sent to the Royal Shakespeare Company “for use in theatrical performance.”

“Alas, poor Yorick” onstage; “Bravo, André” off.

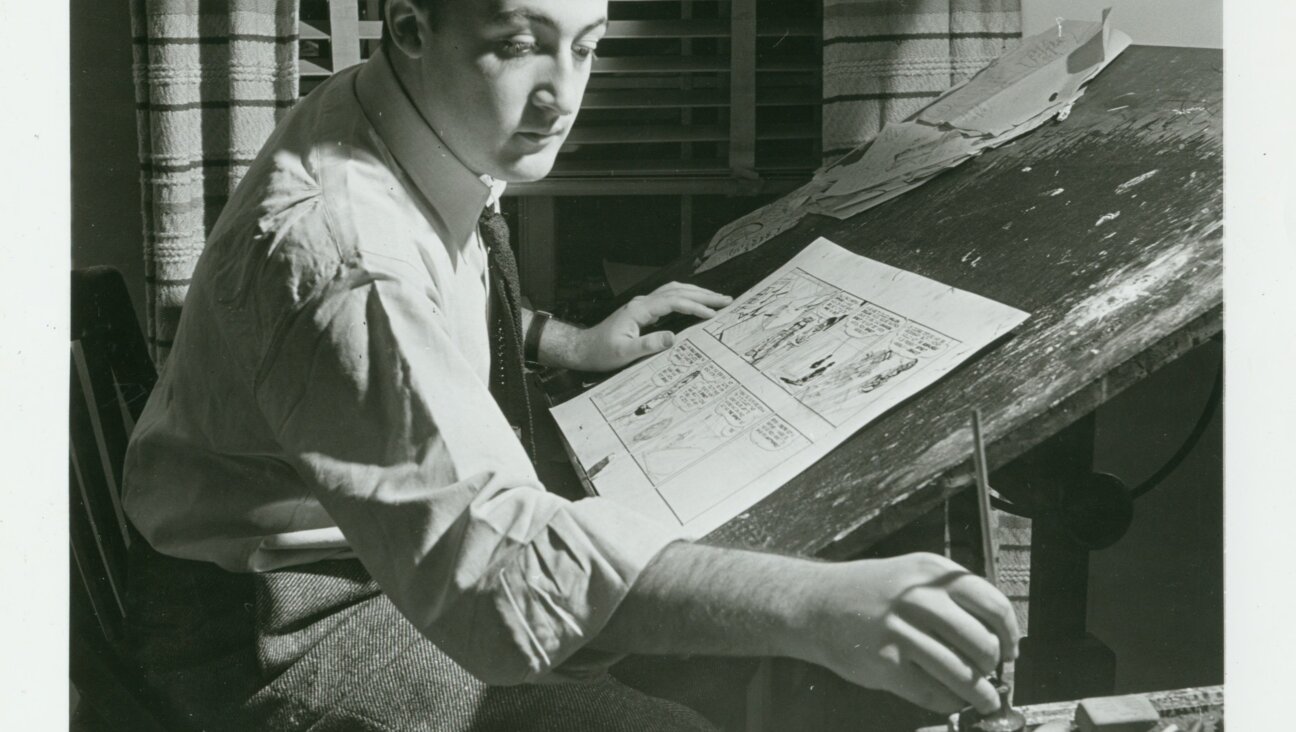

Image by Tchaikowsky Estate

Tchaikowsky’s skull is one of many that have taken the spotlight as the extravagantly mourned jester featured in “Hamlet”; his peers in the role, as The Guardian’s Andrew Dickson today reported, have allegedly included a horse thief, who eagerly left his cranium to the father of the actor Edwin Booth, and actor George Fredrick Cooke, retrieved from the grave for one last turn on the stage.

In more recent history, legendary comedian Del Close left a Tchaikowsky-like provision in his will: “I give my skull to the Goodman Theatre, for a production of Hamlet in which to play Yorick, or for any other purposes the Goodman Theatre deems appropriate.” His creative partner, Charna Halpern, presented the Goodman’s artistic director Robert Falls with a skull she claimed was Close’s after his death in 1999. In 2006, she revealed to The New Yorker that the skull was, in fact, purchased from the Skokie Anatomical Chart Company after she failed to find anyone who would remove Close’s head before she had his body cremated.

The use of genuine human skulls in the part is not exactly common; shockingly, actors and audiences alike tend to be uncomfortable with the onstage use of human remains. The Royal Shakespeare Company has owned Tchaikowsky’s skull since 1982, since which time it has only appeared onstage in one production of the Bard’s most famous tragedy. Where previous Royal Shakespeare Company Hamlets had grown shy of the skull — Mark Rylance, playing the prince in 1989, rehearsed with Tchaikowsky’s cranium but, disconcerted by its origins, discarded it for a fabricated substitute in performance — David Tennant, in 2009, bravely took the skull onstage for each and every show.

(The Company, Dickson mentions, told audiences Tchaikowsky’s skull would be replaced by a facsimile after its presence provoked a distracting fascination. Months later, after the production first transferred to London, then became a film on BBC Two, director Greg Doran revealed it had been Tchaikowsky the whole time.)

Who was the man whose mortal remains created such — ahem — drama? Tchaikowsky was born in Warsaw, to Jewish parents, in 1935, as Robert Andrzej Krauthammer. He and his family were moved to the Warsaw Ghetto after the initiation of World War II. Tchaikowsky adopted the name by which he went for the rest of his life when he was smuggled out of the ghetto in 1942 bearing false papers that labeled him André Tchaikowsky. He lived out the rest of the war in hiding with his grandmother.

After the war, Tchaikowsky studied piano in Lodz, at the Paris Conservatory, and at Poland’s State Music Academies in Sopot and Warsaw. At 15, he gained admission to the Polish Composers Union, and he spent the rest of his life touring as a pianist, often to great acclaim, and finding time, in between concerts, to compose. He had a clear passion for Shakespeare: When he passed away in 1982, at age 46, he left his opera “The Merchant of Venice” a mere 24 measures from completion. Those last notes were eventually added by Alan Boustead; view excerpts from the work, below.

In his famous graveside scene, Hamlet interrogates the skull of his former playmate: “Where be your gibes now? your/gambols? your songs? your flashes of merriment,/that were wont to set the table on a roar?” The moment clarifies both Hamlet’s antipathy towards death and his attraction to it. Often, the prince’s embrace of Yorick’s skull and contextualization of it in terms of the life that once animated it, is staged to strike the audience as uncomfortable, macabre, even cruel.

And yet, if Tchaikowsky’s skull could talk, it would likely provide unexpected answers to its interlocutor’s questions. Where are his flashes of merriment?

Why, just where he intended them to be. The man did once finish off a concert by unexpectedly playing the entirety of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, just because he felt he’d deserved more ample applause. It’s safe to say he knew how to relish an encore.