Why was Freud great? Magic, says Netflix.

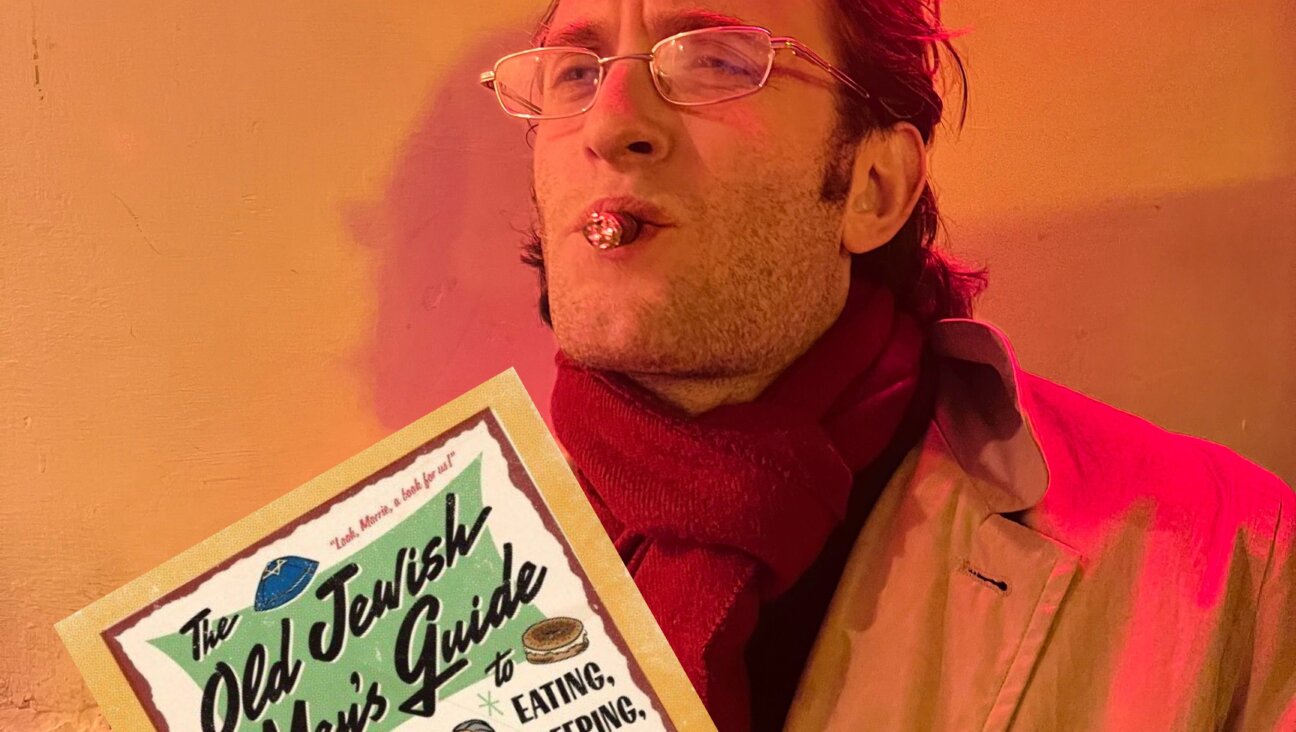

Anja Kling and Robert Finster in Netflix’s “Freud” Image by Courtesy of Netflix, Jan Hromadko

Sigmund Freud couldn’t help but think that he was destined for great things — and, as with so many things in his worldview, the fault lay with his mother.

The future father of psychoanalysis was born with a caul, a bit of amniotic membrane attached to his head. Amalia Freud believed that its presence portended a bright future for her first-born son and raised him with that assurance. In the new Netflix series “Freud,” the young neurologist (Robert Finster) forms a bond with a medium named Fleur Salome (Ella Rumpf), who was born with the same feature. His caul isn’t mentioned in the series, and hers turns out to be a bit of a curse, but the show nonetheless believes wholeheartedly what Amalia did: That this unassuming young physician would one day change the world.

By the first season’s end, he has in fact altered the course of history — but not with his ideas.

In “Freud,” what Freud thinks is secondary to what he does. He’s reimagined as a man of action, and the means by which he leaves his mark are jarringly superstitious and superficial. The show gestures at a great man without bothering to explain what made him great.

Freud meets Salome, the kept mystic of expat Hungarian nobles Countess Sophia and Count Viktor von Szapáry (Anja Kling and Philip Hochmair), at one of the couple’s séances. The Szapárys regularly host gatherings and tableaux vivants in their Vienna home for Austria’s upper-class youth. They are also secret Magyar nationalists looking to free Hungary from the Austro-Hungarian union through the power of hypnosis. Their shindigs are part of an influence campaign to gain access to the Austrian Kaiser by using their undeniable powers of suggestion on their young and powerful guests. More often than not, the Szapárys end up harming innocents by tapping into the latent bloodlust of those under their spell.

Together, Freud and Salome work to solve the Szapárys’ proxy crimes, committed by the well-heeled men they’ve hypnotized. Their method is halfway between magic and psychoanalysis: After talking her through a bad feeling, Freud knocks Salome unconscious, and is then — somehow — able to transport her consciousness to the scene of one of the Szapárys’ bloody deeds, where she can, in a disembodied state, poke around for clues. Don’t ask me how it works.

As biography the show is, of course, a laughable exercise, even if it gets some of the basics right. It’s true Freud was interested in hypnosis in the mid-1880s, the period in which the show takes place. The Szapárys were (and are) a real family — though they weren’t, to the best of history’s recollection, overly-mascaraed psychic terrorists. Freud’s personal life is also accurate to a point, from his engagement to Martha Bernays to his place of lodging in an apartment building that stood on the ashes of the Ringtheater. But, the show and its steam-suffused setting — the roads look like they’re paved with dry ice — seems to care more about these factual flourishes than Freud the man, or what made his particular insights so groundbreaking.

That’s understandable to a point, as the real Freud spent a whole lot more time reading than traipsing around murder scenes. (Murder: exciting; reading: boring.) But the show misses a real opportunity to be more than a gimmick with a historical prop. While the series is hugely entertaining and lovingly crafted — the production value is evident in every detail, from the sabers and shako helmets of military officers to the ritzy antechambers of the gentry’s homes — it founders in all the points that interested its subject. Finster, as Freud, glowers, smolders and radiates a generally discomfiting sexual energy, but his inner life remains opaque beyond his ambition to prove his theories right and the medical establishment wrong.

And even that falters, as he doesn’t really prove much of anything. As Freud takes Salome on as a sleuthing partner he learns of her preternatural abilities to astral project and makes her, in essence, his first private patient. He uses her to test his theories of the unconscious and hypnotism’s applications for hysteria. But, despite having chanced on the supernatural, he doesn’t think to factor it into his analysis and, as a consequence, often seems sort of dumb.

Salome is the more interesting character, but she’s hampered by her backstory, which, as it unfolds throughout the show, frames her as yet another female character defined by distress and trauma. She has rare moments of agency between fugue states, but is just as often a victim. And, because she mainly exists in relation to Freud, her primary function is as a magic sherpa and sometimes guinea pig. She is a means to express his ideas, bring him mystical answers or reveal his caddishness.

That Freud is unlikeable is not a demerit; the fact that he is presented with the aura of a genius-in-progress is.

The series hinges too much on what the audience already knows about his future, and so feels little need to justify why he is at the center of this Grand Guignol adventure beyond the usual, troubled man format teased by his marble-bust visage in the credits. His mother and Fleur regularly speak to his star potential. He’s mocked by fellow doctors, boosting, the dramatic irony for the audience. He has long monologues about the unconscious, which, despite their emphasis feel trite and not nearly as disruptive to the field as they truly were. But rather than build Freud up as a genuinely original and noteworthy character, the show revels in his breakthroughs, which are so peripheral as not to count for much.

When he figures anything out — whether the culprit of a murder or, say, the Oedipus complex — it’s almost always because of Fleur’s abilities and not his own deductions. As a way of mitigating that setup, which would give undue credit to a woman who never existed, the show takes for granted that we already regard Freud as a revolutionary thinker, despite its many suggestions to the contrary.

We’re meant to heed Amalia’s (Marie Lou-Sellem) dinner table prediction that her son’s “name will soon be on everyone’s lips” and put out of mind the personal and professional wreck that Freud has so far made of his life — as evidenced by his cocaine abuse, termination from his hospital job and inability to stay up to date on his rent. Starting from a place of messiness is meant to challenge certain assumptions of a tidy rise, but instead sets the stage for a discordant final act.

In the end, “Freud” executes a heel-turn, having its rebellious lead fall in line with tradition when he returns to his parents’ home for Shabbat to announce his formal engagement to Martha (Mercedes Müller). In past Shabbat scenes, where he’s frequently late, we’ve seen Freud remove the kippah Amalia places on his head. This time, though, he considers the headcovering, puts it on himself and joins the family in singing “Shalom Aleichem.” What is this show of sudden filial piety, this acceptance of old ways he previously objected to? Is it possible his supernatural saga has restored his faith in something greater? I’m still not sure, but I do know that — without spoilers — the close of the season indicates that Freud, quite abruptly, is on his way to becoming the doctor we all know.

By having Freud swiftly surrender to conventionality and faith, the show misunderstands its primary case study. The season appears to conclude in 1886, when the real man’s greatest work was still before him. He certainly never got there by playing it safe. It doesn’t take a Freud scholar to know that his iconoclasm continued throughout his life, notably in regard to his Jewish faith. Surely the show’s creators, Stefan Brunner, Benjamin Hessler and Marvin Kren, the latter of whom also directed, know that. We’ll have to wait for subsequent seasons, if they come, to see how that knowledge might manifest. Perhaps his newly cozy life will face further disruptions that better explain his development.

Maybe, by then, they’ll have figured out what makes Freud special to begin with — instead of just insisting that, by fiat, he is.

PJ Grisar is the Forward’s culture fellow. He can be reached at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

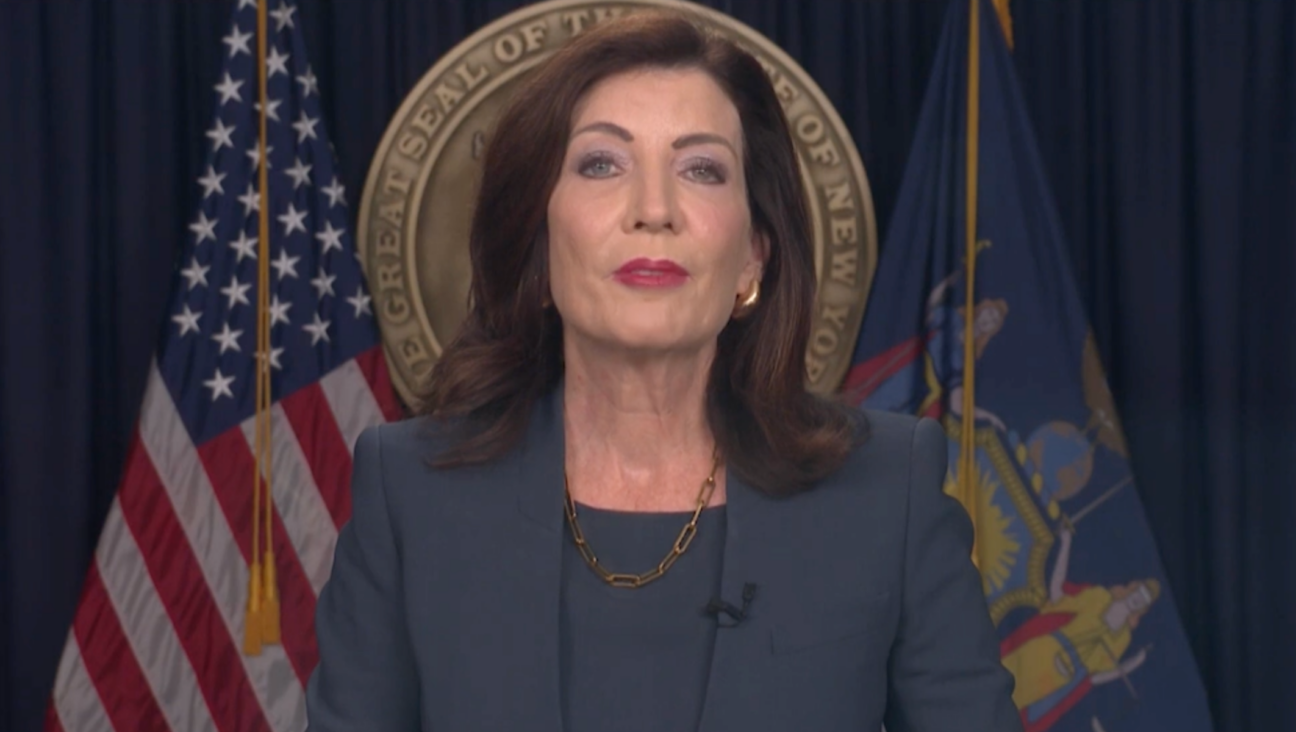

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward In first Sunday address, Pope Leo XIV calls for ceasefire in Gaza, release of hostages

-

Fast Forward Huckabee denies rift between Netanyahu and Trump as US actions in Middle East appear to leave out Israel

-

Fast Forward Federal security grants to synagogues are resuming after two-month Trump freeze

-

Fast Forward NY state budget weakens yeshiva oversight in blow to secular education advocates

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.