Why did this astonishing document of Nazi atrocities vanish for more than 50 years?

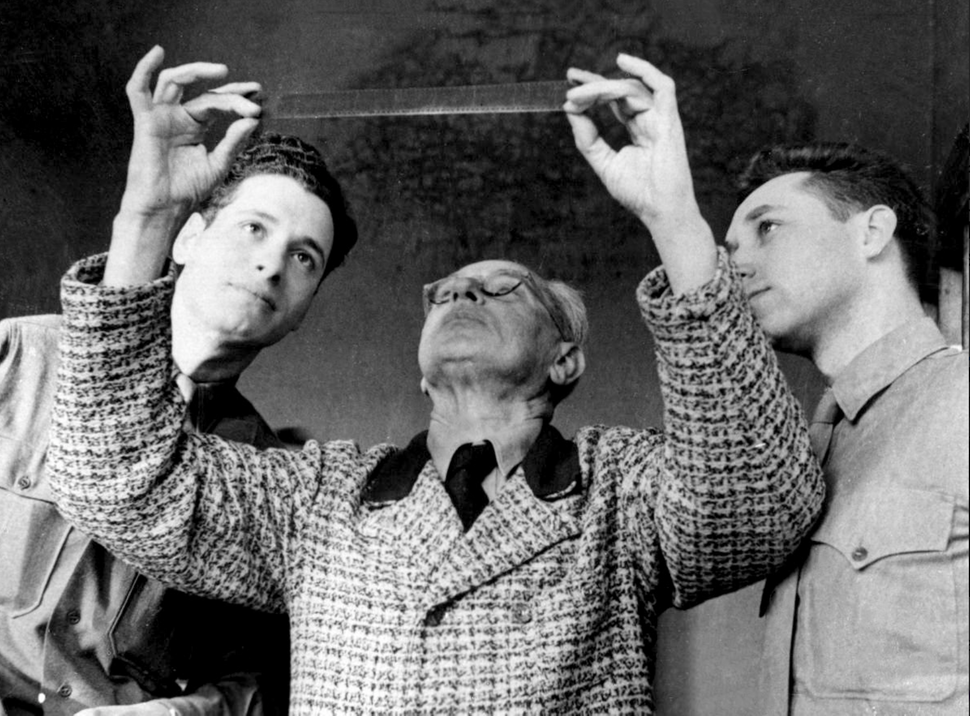

Examining Footage: The Schulberg brothers with Hitler’s photograher Heinrich Hoffman. Courtesy of New York Jewish Film Festival

“The Lost Film of Nuremberg,” which will premiere at New York’s Jewish Film Festival Jan. 13, uncovers a real-life history more unsettling than any saga Hollywood could manufacture.

At its center of the documentary, directed by Jean-Christophe Klotz, is an enigma: How could a film made for and from the historical record become missing from history, and remain so for more than half-a-century? And the ending brings only partial resolution: Because despite the astonishing rediscovery, restoration and wide public release of the re-found film, “Nuremberg,” we are left to review and incorporate anew lessons from the wreckage of the past that remain all too timely.

The story begins in the summer of 1945. Just as World War II is coming to an end, brothers Lt. Budd (1914-2009) and Sergeant Stuart (1922-1979) Schulberg receive the most urgent assignment of their lives: first, to locate original film footage, photographed by the Nazis themselves, of the human atrocities they had committed. Second, to create from those real-life horror films an unassailable documentary record of Nazi war crimes to be presented as evidence at the forthcoming International Military Tribunal, which we more generally refer to today as the Nuremberg Trials.

As the sons of Hollywood movie mogul B.P. Schulberg, the brothers certainly were no strangers to the world of filmmaking. They also had spent their WWII military service working in the documentary unit of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), under the supervision of renowned director John Ford. And they would subsequently forge notable careers themselves in film and television.

But in 1945, their experience was as limited as the stakes were high: 24 prominent Nazi leaders, including Hermann Goering and Rudolf Hess, would be tried for perpetrating, in the words of the tribunal, “crimes against peace, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and conspiracy to commit any of the foregoing crimes.” And the scheduled November start date for the trial would allow the Schulbergs less than four months to complete their task.

In the Cutting Room: Bob Webb in the background, Stuart Schulberg in the foreground. Courtesy of New York Jewish Film Festival

Suspense reigns as the documentary follows the brothers’ journey through the wreckage of rubble-filled Germany to uncover Nazi records. More than once, they rush to a remote hiding place they had been tipped off to, only to discover that an incriminating film cache had only hours before been incinerated in an “accidental” fire. Had a German collaborator been tipped off?

They also got lucky. In a talk given towards the end of his life, Budd Schulberg, by then known as the Oscar-winning screenwriter of “On the Waterfront,” among other films, recalls getting nowhere in his attempt to convince a Soviet officer to allow him access to the vast numbers of German newsreels stored in areas under Soviet control. That is, until Schulberg happened to mention he was working for John Ford.

“Djonford!” the Soviet officer exclaimed, pronouncing the name in one word, commencing an animated commentary on Ford’s greatest films — and granting permission to use whatever films they found in Soviet-controlled storage areas. Budd Schulberg also arrested German film director Leni Riefenstahl and brought her to Nuremberg, where she reluctantly agreed to identify various Nazi officials and supporters who had appeared in her propaganda films.

All this was prelude to the final race to shape from the 500,000 feet of film they had gathered an authoritative visual document that would expose the regime’s barbarous actions more dramatically, and indelibly, than words alone.

They met the deadline. But there was even more work to complete before they could screen it before all those assembled for the trial. That is because another U.S. government film, this one about the Nuremberg trial itself, was already being planned, with Stuart Schulberg as director.

It is thanks to his last-minute logistics in adjusting optimal lighting and camera angles that we today have the extraordinary reaction shots of the defendants themselves. We see Goering sniggering in the moments before the lights go down. Then, his grim silence, after viewing four hours of one harrowing Nazi action after another, each scene witnessed and captured on film by cameramen and photographers who were themselves affiliated with the regime.

At the Premiere: Stuart Schulberg with John Scott Courtesy of New York Jewish Film Festival

Yet those images — which Schulberg included in his astonishing documentary about the trial, titled, simply, “Nuremberg” — remained unseen for decades, as did the film in the entirety of 75-minute running time.

That is because, this new documentary reveals, by the end of 1948, the start of the Cold War had put on ice any possibility for it to be screened in the U.S. Even though the film had already been distributed throughout Germany, with America trying to rebuild Europe through the Marshall Plan, U.S. government officials declared that the American enemy was no longer the Nazis, but the communists and Soviets. And so the Iron Curtain cast its own shadow on Schulberg’s film.

Fast forward to 2003. As she was going through her mother’s home after her recent death, Stuart Schulberg’s daughter Sandra Schulberg stumbled across what had been hidden in plain sight all along: boxes filled with more than 300 pages of letters from her father, numerous documents relating to the film, and the deteriorating film reels themselves.

Until then, “I wasn’t even aware of the movie,” Schulberg, a movie producer and independent film activist, said in a telephone interview from her home in Los Angeles.

But it soon became her mission to piece the puzzle together and restore it. Even so, she soon realized, “I had to have outsiders help interpret the material for me. I’m not a historian, I’m a movie producer.”

She turned, among others, to Raye Farr, then director of the Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive and of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Permanent Exhibition. As they went through the documents and film footage, Farr put together the meaning of the gruesome film footage that had been handed to Stuart Schulberg too late to include in the four-hour film shown at the trial, but that he had nonetheless added to the shorter film: a shocking scene in which emaciated, naked men and boys are led into an otherwise sealed house into which pipes are funneling gas exhaust fumes from the running automobile to which the tubing is connected. It probably took place in 1941, in Mogilev (now in Belarus), Farr deduced, and was one of the first Nazi “experiments” in asphyxiation and a prototype for the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

Working together over the next years with filmmaker Joshua Waletzky, Schulberg succeeded in restoring the original film and — finally, in 2010 — releasing it, under the title “Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today.”

But for audiences today to understand the film in full, it needed additional context, Sandra Schulberg believed. “As I traveled and showed the original documentary I found that people generally knew very little about the Nuremberg trial itself, and to some extent even about World World II and the Holocaust,” she said in the interview. Even so, she found, “they were consumed with wanting to learn and know more.”

Schulberg and Klotz will be present for Q & A sessions after both screenings Jan. 13. In addition, the film distributor Kino Lorber plans to release together both the restored Stuart Schulberg film from 1948 and with the new Klotz documentary about how it was lost and has now been found, thus delivering once again lessons we still need to learn.