This punk rock legend survived the Holocaust — and she’s still singing and fighting

Genya Ravan, who has been making rock ‘n’ roll history since the 1960’s, has no plans to retire

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

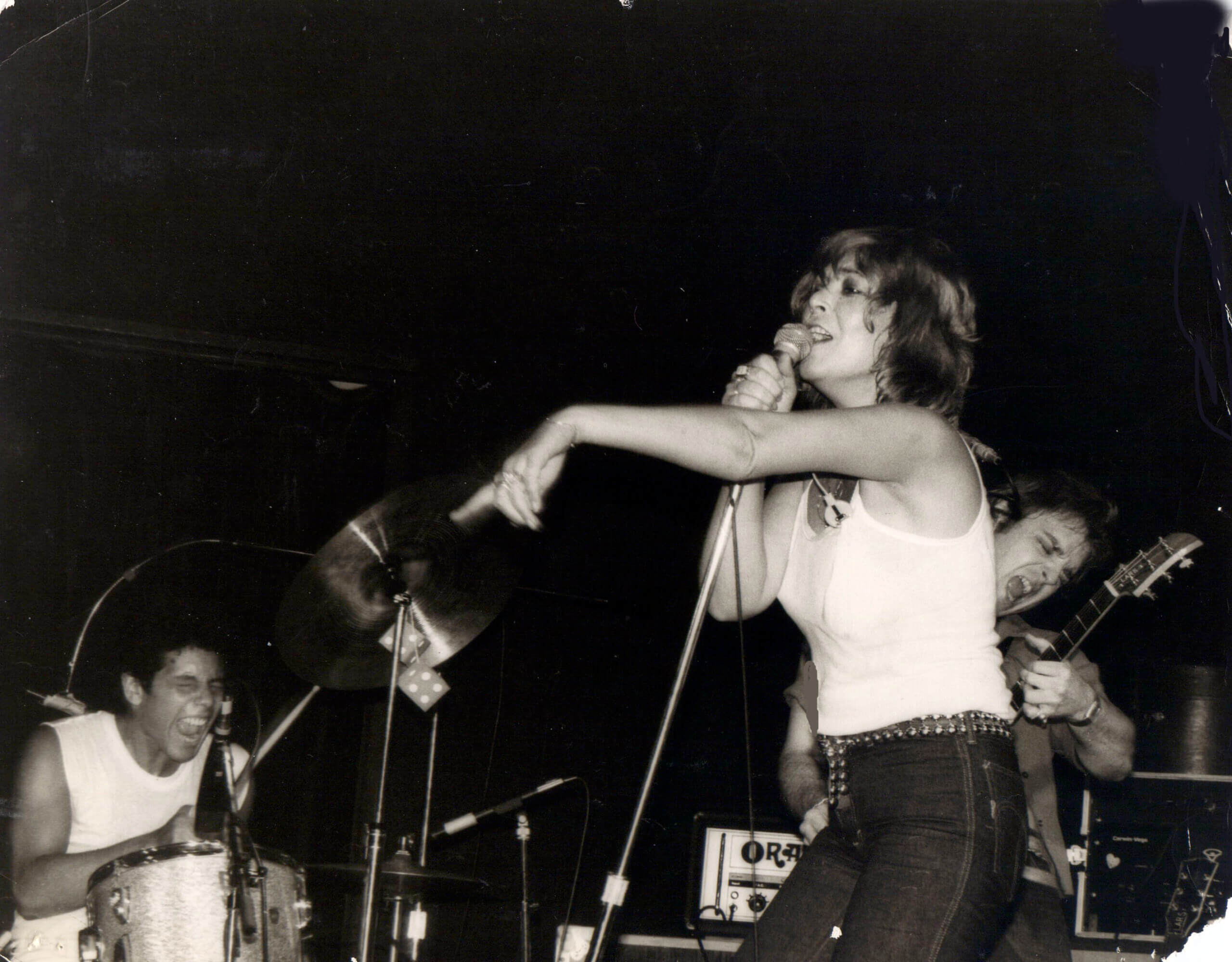

“Youse broads know howta play?!”

That was the incredulous question — or maybe a slightly veiled accusation — that club owners would ask singer Genya Ravan, then Genyusha “Goldie” Zelkovicz, when she and her group, Goldie & the Gingerbreads, tried to book gigs during the early 1960s.

Ravan had a defiant answer, evincing the kind of attitude that would serve her career well over the ensuing decades: ”’Yeah-yeah-yeah. Wait ‘til ya hear us, we’ll knock your socks off.’”

“Mine was an all-girl band and I’m in a man’s world. What else am I gonna do?” she said.

That was the universe in which the first rock band without a male musician took shape. By the mid-‘60s, Goldie & the Gingerbreads were touring Europe, opening for the Yardbirds, Rolling Stones and Kinks.

Still, the attitude persisted: Sure, girls – or women – could sing. Some of them. But play in bands? All together? In years to come, there would be Fanny, The Runaways, The Go-Go’s, The Bangles, The Slits and many more.

After Goldie & the Gingerbreads, broke up in 1967, the young singer briefly formed a trio with jazz drummer Les DeMerle, and decided to change her name. “You sound so Black you should call yourself Raven or something,” DeMerle told her.

“I did,” she said, “but I didn’t want to spell it the same.”

Within a year, Ravan began fronting the band blues-jazz-rock band Ten Wheel Drive, the first conceived with a woman as the lead singer. There was much more music after that, as a solo artist, as a producer and currently, as a DJ, hosting two shows on SiriusXM.

“I’ve got a strength in me and that comes from my Jewish heritage,” Ravan said, on the phone. “The fighting came from the way I was brought up. My parents couldn’t afford rent for $35 on Rivington Street and we lived that way for many, many years. So, we were poor. I didn’t go out and steal, go out and mug or go out and kill. I went out and worked.”

Ravan, who just turned 82, was raised on New York’s Lower East Side and now lives in upper New York State. But as to how she got here?

The long road from Poland to America

Ravan was born in Lotz, Poland, in 1940. Her older sister and parents were transported to a Nazi work camp — or a “civilian forced labor camp” — where their job was to manufacture bullets. Genyusha was not with them. Her mother, hiding in a cellar, had given her away shortly after birth to another family for safekeeping. Two of her brothers, her grandparents and numerous aunts and uncles died in concentration camps.

After the war, six-year-old Genyusha was reunited with her parents and they were relocated to a Russian displacement camp.

“They tried to do whatever they could with leftover camp people, the Jews,” she told me. “I remember the bunks were like stalls, one of top of another. I remember waiting on line for food, and I remember the truck – running to a truck to pick up shoes from people that had died.”

In 1947, they managed to escape. “We didn’t get an OK to leave,” she said. “I actually remember the escape because my mother had her hand on my mouth while we were crossing a field at night where the grass was higher than me. We were all on the ground, going towards this one woman. I don’t know who she was, but I remember reaching her and she got us to the trains immediately.”

“The train we traveled on, it was horrible,” said Ravan of the journey they took to a Russian port of departure. “There were so many people, you just couldn’t get more bodies in. My mother was on the inside steps of the train. She had my sister on her back and my father was on the outside on the steps of the train, if you can imagine it, because he’s stronger. Who is outside him? Me. My sister was older and heavier and my father tried to carry both of us. I remember that it scared the hell out of me, my father saying to my mother, ‘Yadja! Yadja! I can’t hold on much longer.’

“And as he said that I’m looking down and we’re on a bridge and all there is is water. If he fell, that would have been the end.”

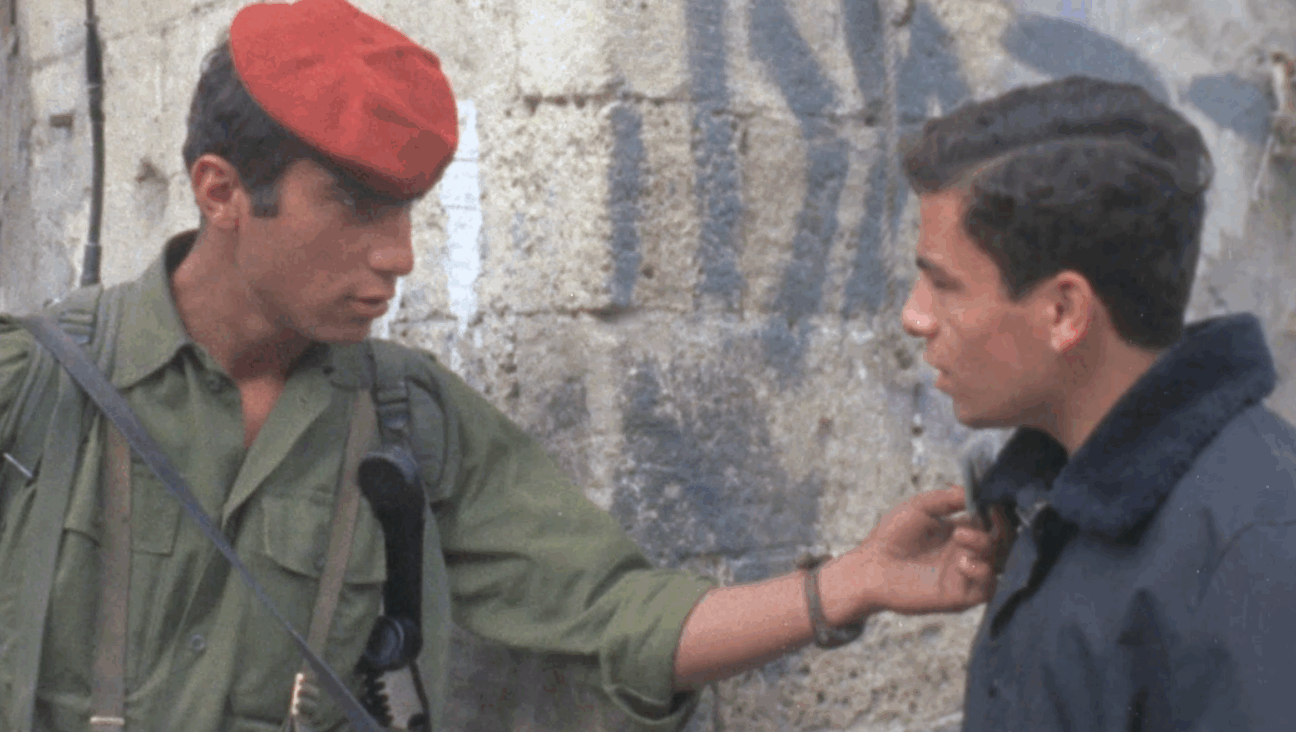

“We were passing as Polacks, not Jews,” Ravan said. “I remember an open truck and a soldier — who was on what side I don’t know; he gave me an apple.”

“After that, all I could tell you is my memory as a seven-year-old at that time was being inoculated and interviewed, getting in trouble for the interview when we left Russia. My mother must have sewn $50 in the liner inside my coat thinking nobody will check a little girl. I go in and they interview everybody alone in my language, which is Polish or Russian or Yiddish, I don’t know, and they said to me ‘Do you have anything in my coat?’ and I said ‘Yeah, I have something in my jacket, it’s in here.’ They took the money.”

The Zelkovicz family didn’t know where they were headed, just that they would be on a ship. Ravan doesn’t remember the actual boarding, but recalls it being “the worst winter. I remember being on the deck with life jackets on and it was very scary.

“We didn’t take the United States ship on purpose. We were taking any ship that was going out. One was going to Israel — which was Palestine at the time, I think — and one was going to the United States. We just grabbed a ship. I’m so glad it was to the United States.”

Life after the ‘Gingerbreads’

After Goldie & the Gingerbreads went down, Ravan fronted Ten Wheel Drive from 1968 to 1971, and moved the ensemble from a Broadway kind of sound toward rock ‘n’ roll and R&B. (The band continued with another singer through 1974.) Ravan went solo and evolved into a punk/new wave singer and producer, and performed duets with Lou Reed and Ian Hunter along the way.

Reviewing her 1978 album, “Urban Desire,” Village Voice critic Robert Christgau called Ravan “a real New York doll.” Ravan, Christgau said, “is a woman who combines the hip cool of Lou Reed with the emotionality of Springsteen [and] a case of Joplinitis.”

Ravan has released eight albums under her own name, the latest being 2019’s “Icon.” While Goldie & the Gingerbreads were signed to a major label, they never released a full album; that was rectified last year with the release of the 20-track album “Thinking About the Good Times: The Complete Recordings 1964-1966.”

Ravan has many tales from her years as a producer, two of the most notable perhaps being Dead Boys in 1977 and Ronnie Spector in 1980.

In the case of Dead Boys, Hilly Kristal, Ravan’s friend and owner of the New York punk rock club CBGB, invited her down to his Bowery dive to listen to a group he managed, this punk band from Cleveland.

“I go down a month later,” she said. “I’m standing by the sound booth and they’re doing this song ‘Caught with the Meat in Your Mouth.’ Hilly turned around to me with a smile and said, ‘Aren’t they charming?’ And I thought ‘Charming, they’re not!’”

“I thought they were so unprofessional and then I went, ‘Wait a minute, this is how you started, Genya.’” Ravan said. “Then I started to fall in love with that whole unprofessional scene. Because I was on both sides of the glass, I was able to be the best audience for a new band. I came from the same school, worked the bars. It didn’t take me long.”

The first album she worked on — “Young, Loud and Snotty” —would turn out to be one of the best LPs of the punk rock era. But Ravan had a little problem right away.

“We go into the studio and they load in. I see their trap boxes and every one of them has got a swastika on them. I’m in the room with the equipment and them and Hilly and I said, ‘You know you’re surrounded by Jews here in New York City? I know that that [sporting swastikas] is the fad, but you’re talking to people who have felt the wrath of this sign. Either those swastikas come off or I’m not working with you. I’m a Jew, a surviving Jew from the Holocaust.’

“And the drummer [Johnny Blitz] goes, ‘I don’t even know what it means.’ I said, ‘Exactly. Your manager, Hilly, is a Jew. Not only that, the owner of Electric Lady is a Jew with numbers on his arm from being in a concentration camp. Does that make any sense to you that you have swastikas with all of us Jews supporting you?’ They took ‘em off.”

For Ronnie Spector, who died in January of this year, Ravan produced “Siren,” which was intended to bring the Ronettes singer into the punk/New Wave era. For the album, Ravan suggested that Spector cover the Ramones’ song “Here Today, Gone Tomorrow.”

“When I played it for her,” Ravan said, “she looked at me like I had two heads ‘cause, well, the Ramones do it like they do it. I had her cut it and it became her single. I ran into Tommy or Joey, not sure which, at CBGBs and said ‘Hey, I had Ronnie Spector record one of your songs, “Here Today, Gone Tomorrow”’ and he said, ‘Oh my f–king God, we wrote that with her in mind!’”

Ravan says Spector’s widower, Jonathan, called to thank her not long after her death, saying, “She needed what happened with you. She was stuck and it was good what you did.”

Ravan’s next chapters

In 2004, Raven wrote the memoir “Lollipop Lounge: Memoirs of a Rock and Roll Refugee.” She has produced scads of bands, but says she isn’t courting that work now. She’s been developing a treatment for a TV show she won’t get into details about. And she says she’d like to mount a rewritten version of the musical about her life, “Rock & Roll Refugee,” which ran briefly off-Broadway in 2016. Her most recent release was 2020’s bluesy, soulful and sassy rendition of “I Who Have Nothing,” which Tom Jones popularized in 1970.

These days, her main gig is hosting two SiriusXM shows for Little Steven’s Underground Garage — “Chicks and Broads,” which began in 2012, where the focus is music made by women, and “Goldie’s Garage,” which started the following year and features unsigned bands from around the world.

When you hear Ravan as a DJ, you’ll hear her unmistakable and unshakeable Lower East Side accent. “I can’t even listen to my own radio shows because I hate the way I talk” she said with a raucous laugh. “But I love the way I sing.”

She says there may be another album in the works. “I’ve been lazy,” she said. “I’ve got all my lyrics, but I’ve got to be surrounded by musicians more and I’m not right now.”

When she was younger, Ravan – like many – partied with the volatile mix of alcohol and cocaine, the use of one substance enabling further use of the other.

“I was like a gerbil in a cage,” she said, noting she’s been sober 31 years now. And. after living for 16 years with singer/guitarist John Lee Cooper, who’s 11 years her junior, she married him this year on Valentine’s Day.

“I’m not looking to screw around anymore,” Ravan said with a laugh. “I never liked older men – they scared the hell out me.”

As for retirement, Ravan told me, “Retirement to me means when I leave the planet. I can’t retire. My chemotherapist from Memorial Sloan-Kettering, who saved my life from lung cancer, said to me when he came to one of my gigs in New York City, ‘That’s why you made it. Don’t ever thank me or the hospital. You are a survivor and a fighter.’”