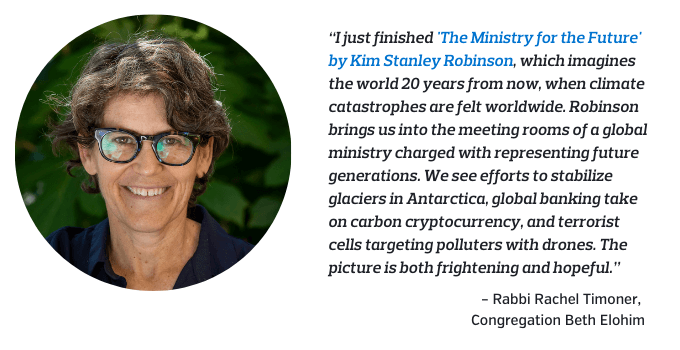

New Yiddish stories and nonfiction for ‘Mrs. Maisel’ fans: The Jewish books you need to know this spring

Our favorite new releases, plus a trip to New York’s antiquarian book fair

Photo by iStock

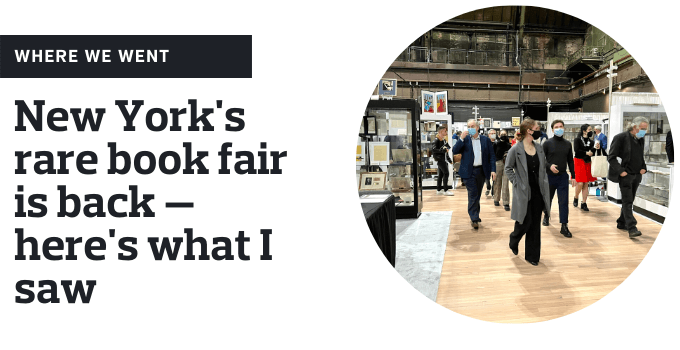

Welcome to Books Briefing, your monthly tour of the Jewish literary landscape. I’m a culture writer at the Forward, and I spend a lot of time combing through new releases so you can read the best books out there. Recently, I took a field trip New York’s antiquarian book fair, where there’s lots to look at — although, unless your budget includes hundreds of dollars for first editions, not much to take home.

You can shop these recommendations at our Bookshop storefront. If you make a purchase from our page, the Forward will earn a small commission. This article originally published in newsletter form; if you want to get Books Briefing in your inbox, you can sign up here.

The New York International Antiquarian Book Fair last convened in March 2020, the eve of the coronavirus pandemic. This month, the fair has finally returned to the Park Avenue Armory — with masks and hand sanitizer, of course. Ahead of the opening, I took a field trip to the armory, where over 200 purveyors of rare books — as well as notable letters, photos, and even autographs — were setting up their booths in the armory’s airy atrium.

I’d come to the fair expecting to find capital-J “Judaica,” a term I’ve always associated with hoary machzorim and gilded haggadot. The fair certainly pulled through on that front: At Shapero Books, I paged through (yes, they let you touch stuff! And yes, it’s really cool!) a set of leatherbound High Holiday prayer books embossed with intricate gold designs for David Sassoon, the 19th-century patriarch of a storied Baghdadi Jewish merchant family.

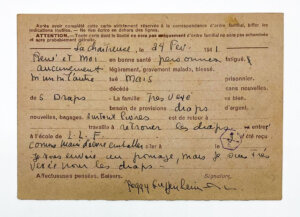

But much of the Judaica on display was more modern, and less expected. Rebecca Romney and Brian Cassidy of Type Punch Matrix showed me a telegram from Peggy Guggenheim arranging the evacuation of her extensive art collection from Vichy France — essential works by Picasso, Chagall, Braque and others that might easily have been deemed “degenerate” by Nazi authorities and destroyed.

The telegram represents a crucial moment in the history of modern art. Yet Romney predicted it would prove less popular than the store’s collection of books from the library of Amy Winehouse. These books, many dog-eared and marked up by the singer with annotations and doodles, are especially dear to Type Punch’s owners as well. When they opened her edition of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” Romney said, “we got actual chills.”

I got my own chills at Budapest-based Földvári Books. There, I got to hold an issue of Der Shtrom, a Soviet Yiddish literary journal, with a cover designed by Chagall. Földvári is also displaying a first edition of “We Were at Auschwitz,” a 1946 memoir by three Polish survivors which, in its original printing, was bound in cloth from a real concentration camp uniform. I’d seen those blue and white stripes before in so many photographs, movies, and museums, but I’d never touched them. It’s an experience I don’t need to have more than once.

Until recently, this book barely existed. Chana Blankshteyn, a well-known journalist and organizer in interwar Vilna, published this collection of Yiddish short fiction in 1939 — just weeks before the Nazi invasion of Poland, as well as her own death. During the war, two copies made it to Yiddish libraries in the United States — and there they remained, for decades. A new translation from scholar Anita Norich means that “Fear” is available to English readers for the first time. (Norich is the sister of Sam Norich, a previous publisher of the Forward and the current president of the board.) The collection is the latest in a slew of new translations of female Yiddish authors whose work shows how historical forces shaped women’s lives: You can now read Blankshteyn alongside previous Books Briefing picks Fradl Shtok and Miriam Karpilove.

I blazed through these nine stories in the course of a morning. All set in the aftermath of WWI and the Bolshevik revolution, they detail the hazards of living as a Jew in a wartorn, impoverished country threatened by various occupying powers. (Between world wars, Blankshteyn’s Vilna was volleyed between Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union.) While reading, I frequently had to remind myself that Blankshteyn died without confronting the Holocaust, because her anticipation of it is so sadly prescient: In “Director Vulman,” a Jewish factory manager sees his carefully ordered world demolished by newly emboldened Nazi thugs.

My favorite stories, though, are the ones that capture the hope and potential for Jewish life in the interwar period — a sense of optimism that modern readers, burdened by hindsight, rarely experience. Andrée, the protagonist of “The First Hand,” is an impoverished Parisian with almost no knowledge of her Jewish heritage. She claws her way to success as a couture seamstress, her skill and self-sufficiency evoking Blankshteyn’s labor activism. But her yearning for community and self-knowledge only ends when she falls in love with Miguel, a Spanish crypto-Jew whose family has been practicing in secret for generations. Their wedding provides a glimpse of a world in which Jews draw together even as they throw themselves into modern, cosmopolitan societies. It’s a vision that never came to fruition in Blankshteyn’s lifetime.

What would you do if your personal happiness became a metric of professional success? This is a serious problem for Evelyn Kominsky Kumamoto, a PhD student who has abandoned the bleak horizons of academia for a cushy job at “the third-most-popular internet company,” where she works on an app to measure and improve users’ happiness. Developers are expected to use the app — and achieve good results — but Evelyn has too much going on to record a straightforward journey towards complete happiness. Her relationship with her father, tense since her mother’s death, is challenged by his new girlfriend. Her boyfriend is dead set on marriage, while she’s dragging her feet. And in the novel’s second act, she finds herself pregnant with a baby she’s not sure she’s ready for.

Evelyn finds it even harder to categorize her identity than her happiness: Jewish on her mother’s side and Japanese on her father’s, she struggles to feel at home in either culture. Her father’s girlfriend Kumiko is astonished that she doesn’t speak Japanese and isn’t familiar with traditional dishes. And while she was raised and dutifully bat mitzvahed in a Jewish home, she’s rarely perceived as Jewish. Instead of shoehorning Evelyn’s identity into an unrelated plot, Stanford uses it to augment the novel’s fundamental argument: an insistence that we see and value the relationships, feelings and experiences that cannot be easily labeled. Stanford’s take on corporate wellness culture — it’s crap — isn’t exactly novel. But her use of hybrid identities to critique Big Tech is smart and meditative enough to justify a break from all our various apps.

The next season of “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” is a long way off. But in the meantime, Shawn Levy’s new history of women in stand-up tells a story much more complicated — but often just as glamorous — as Midge’s. In the mid-20th century, where Levy focuses, the vaudeville scene was giving way to the format now familiar from a thousand Netflix specials: one man (or, for Levy’s purposes, one woman) in front of a microphone, firing off as many jokes a minute as possible. Around this time, female comics shifted from playing slapstick “personas,” often based on misogynistic stereotypes — the flighty mademoiselle or the dowdy mother — to insisting that they could mine their ordinary lives for humor just as well as men.

The comedians Levy chronicles, many of them Jewish, are irresistible in their wit, their one-liners and the bravado with which they faced down the sneering condescension of their male counterparts. There’s Jean Carroll, who formed a comedy duo with her husband in which she was the acknowledge talent and he the bumbling straight man — in their era, a novelty. And there’s Belle Barth, whose jokes were so dirty she had to tell the worst parts in Yiddish. Despite these precautions, she still got hauled up in court several times for her “foul, filthy, and obscene language.” (In the age of Amy Schumer, however, her jokes don’t raise eyebrows quite so high; reading some of her one-liners, I struggled to find the dirty joke.)

On the page, it’s a little difficult to grasp the meat of these routines; stand-up comedy is spoken, rather than written down in books, for a reason. But Levy is adept at weaving personal lives into the story of a culturally and politically explosive moment. After all, it matters whose lives we consider funny, whose lives we consider relatable — whose lives we consider human.

This children’s biography of Frank Gehry will teach your child the meaning of the word “undulate,” the location of the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and the lasting burdens of family trauma: “He thought I was a dreamer,” the fictional Frank opines of his father. “He didn’t think I would amount to anything.” Yes, it’s very intentionally precocious, but it’s also a winning exploration of the architect’s life and work.

Blumenthal finds charmingly childlike language to describe buildings that often reduce onlookers to jargon: Bilbao’s Guggenheim museum, in her words, is a building with “billowy blanket walls, big enough to hide a family of dinosaurs.” She focuses on childhood moments that influenced his later work, like molding his grandmother’s excess challah dough into different figures. But she also takes on adult topics, like Gehry’s decision to anglicize his surname to avoid antisemitism in his profession. Recommended for any kid in need of new facts for the dinner table.