A new exhibit shows how Jewish marriage evolved – from 12th-century Egypt to modern-day America

The first show at the JTS library’s new gallery has rare ketubot from different centuries and continents

An illustration from a 1683’s “Ecclesiastical Customs and Practices” from Amsterdam, translated to Dutch from the original text written by Italian rabbi Leone de Modena. This scene shows the marriage party under a domed, star-embellished “huppah.” Courtesy of Jewish Theological Seminary

In 12th-century Cairo, a man and woman were getting married – for the second time.

This time, the bride had conditions: Her mother would live with them, and her husband was not to strike or degrade his mother-in-law. We have this window into Medieval Egypt from the Cairo Genizah, a massive cache of documents found in the storeroom of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat (Old Cairo). If you visit the Jewish Theological Seminary in Morningside Heights, you can see the historic prenup up close.

“To Build a New Home: Celebrating the Jewish Wedding” is the first exhibition at JTS’ new library, designed to show off the seminary’s vast holdings and to welcome visitors to a more accessible collection, no longer up a flight of stairs, but at the end of a sunny atrium. The nuptial theme was a natural fit for the library’s new home

“We want to inspire people, we want to educate people,” said David Kraemer, JTS librarian and professor of Talmud. “The only way to do that is to make the library present and upfront and the rare material and to have an exhibition gallery.”

The gallery is small, but the artifacts are fascinating, ranging from fragments of the Genizah to a 15th- century Yemeni Bible and the Rabbinical Assembly’s 2012 pamphlet “Rituals of Marriage for Same-Sex Couples,” which provides guidance for Jewish clergy conducting gay weddings.

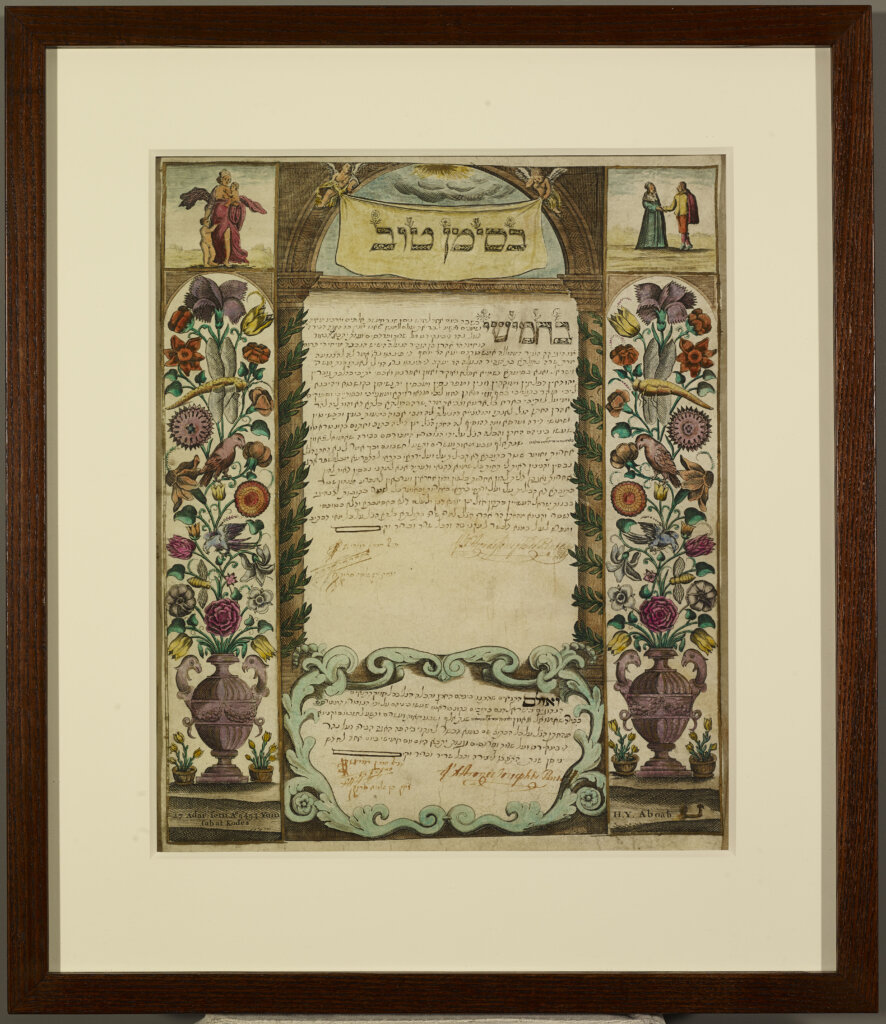

Curator Sharon Liberman Mintz hoped to highlight how ketubot across continents and centuries retained similar features as they evolved. While the essential boilerplate text was standardized in the early Medieval period, the small sample of artifacts displayed at JTS reveals how Jews adapted to the artistic mores and customs of the countries where they lived.

Italian marriage contracts, often made by Christian artisans, show common pagan symbols and Renaissance decoration alongside Hebrew verses. (You can tell the Italian ones on sight, with one of them featuring a pre-fig leaf Adam and Eve.) A ketubah from the Hague, meanwhile, using a common printed frame, features the Baroque figure of Charity. (One from 1729 is hand-painted, overriding the likely aim to curb extravagant customized manuscripts among the Sephardic community in the Netherlands.)

In display cases below many of the hanging ketubot are woodcut-illustrated volumes, mainly written for European Christian consumers, that give us insight into the development of Jewish wedding rituals. A Portuguese Sephardic couple is shown tying the knot indoors, while an Ashkenazi couple gets hitched in the courtyard of the synagogue. If you look carefully at the depiction of German Jews circa 1749, you can make out a goblet getting smashed against a star-shaped stone outside of the synagogue. This book, like many others on Jewish life, was by a Christian Hebraist.

“The best sources for what Jews were actually doing were the Christian reports, because in the Jewish record they describe what we’re supposed to be doing,” Kraemer said. “In Christian record they say what people were actually doing.”

An exception to this rule is Kraemer’s favorite piece on display: a 1204 copy of the halachic text Mahzor Vitry from Northern France, one of the earliest full records of Ashkenazi customs. Illustrated with a hunting scene typical to its time and place of origin, it also includes a page with the text of a wedding song that alternates between Hebrew and French, with the Hebrew lines alluding, via double entendre, to the marriage’s consummation.

The artifact I like best comes from an eccentric entrepreneur and charlatan named Abraham Hochman, who owned a Lower East Side wedding hall and also styled himself as a seer and palm-reader. Dating from 1911, the ketubah looks like a mix between a blank stock certificate and the sort of decorated frame you might get at the end of an amusement park ride, with a hole cut out for a snapshot of the bride and groom. While the Hochman certificate on display is blank, others have telling details about individual newlyweds and how they lived.

Mintz showed me a 1749 ketubah from Venice marking the marriage of an Ashkenazi groom and a Sephardic bride. Following the Sephardic model, the document has both the text of the ketubah and the tena’im, or conditions of engagement. One of those terms reads, “in case of a quarrel, God forbid, between them, they shall follow the customs of the Ashkenazim in Venice in this matter.” Not much of a compromise from the groom in this instance.

“You encounter a ketubah that’s 800 years old and you encounter the continuity of this wonderful practice which was really put into place to protect the rights of the wife,” Mintz said. “I think most people aren’t aware of how beautiful these objects could be.”

“To Build a Jewish Home” is on view at the Jewish Theological Seminary through August 2022. More information can be found here.