The Jewish musicals that Oscar Hammerstein never got to do

The lyricist and playwright considered writing about dybbuks but spent more time immortalizing the life of a singing nun

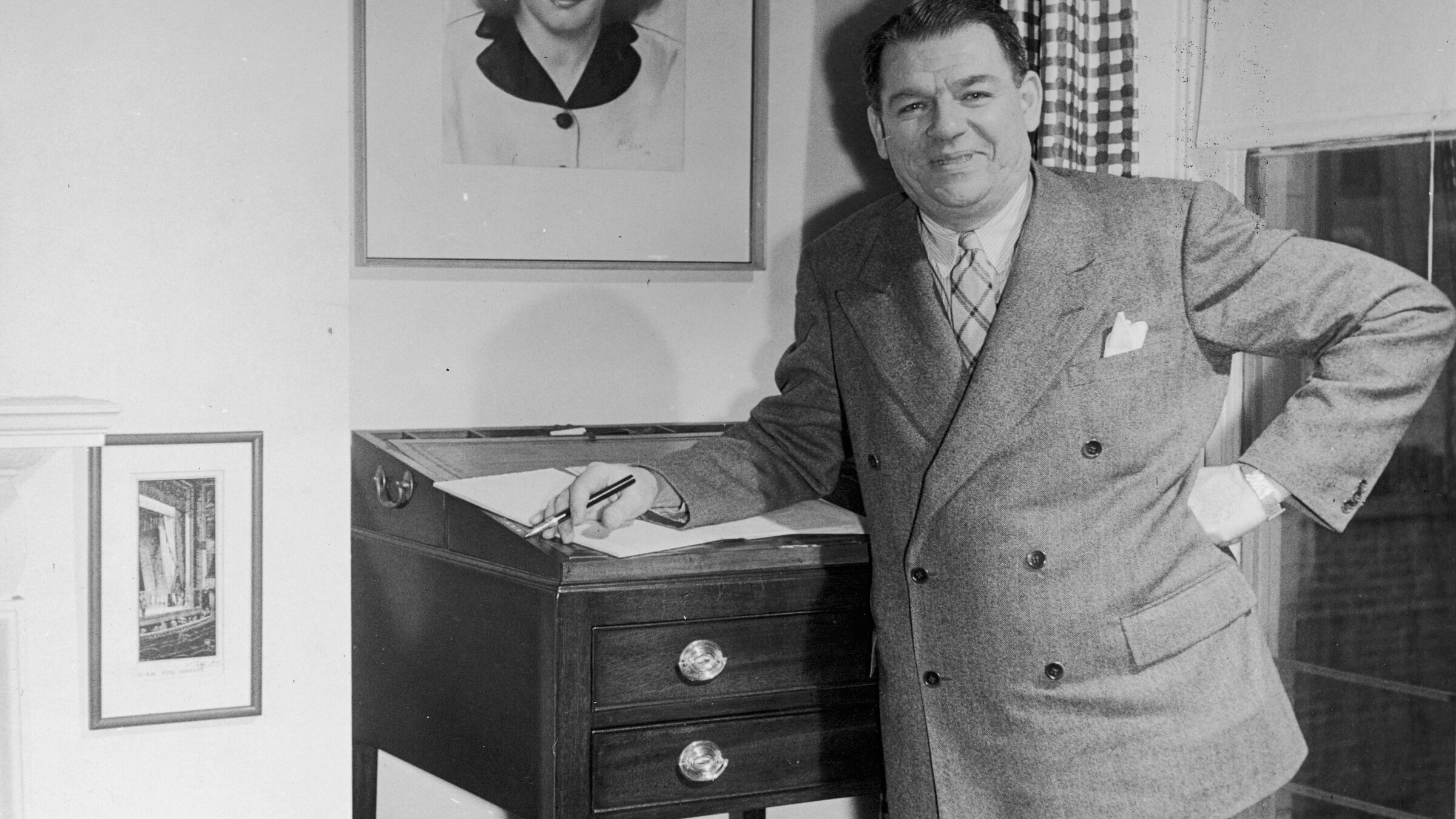

Oscar Hammerstein II. 1945. Photo by Getty Images

The lyricist and playwright Oscar Hammerstein II is credited with inventing the modern Broadway musical by collaborating with Jewish composers such as Jerome Kern on “Show Boat” and Richard Rodgers on “Carousel,” “Oklahoma!” and “The Sound of Music.”

Despite all the singing nuns in the last-mentioned work, a new collection of Hammerstein’s letters published by Oxford University Press implies that there was Yiddishkeit in Hammerstein’s inspiration and even a thwarted early project with material that later inspired “Fiddler on the Roof.”

Benjamin Ivry recently spoke with the book’s editor, Mark Eden Horowitz, senior music specialist in the music division of the Library of Congress, about how Oscar Hammerstein’s Jewish roots influenced his creation of a serious, progressive musical theater that delighted America and the rest of the world.

Benjamin Ivry: In 1954, Hammerstein wrote to the actor Stuart Scadron, describing himself as “your affectionate Episcopal, Jewish, Mohammedan godfather.” What did he mean?

Mark Eden Horowitz: [Hammerstein] was not a religious fellow, but I think he was a deeply good fellow and I guess a humanitarian, but did not attend services. I think he thought of himself as culturally Jewish.

Around 1926, Hammerstein saw two productions of S. An-sky’s play “The Dybbuk” as potential material for musical adaptation at New York’s Neighborhood Playhouse and Yiddish Art Theatre. Hammerstein wrote to his uncle that taking up the project would mean “to cast aside all other plays, study up on Jewish lore and tradition, saturate ourselves with the atmosphere of the thing and leave nothing undone to make it perfect.” Given his later reliance on personal inspiration over historicity for ethnic subjects in “South Pacific,” “The King and I” and “Flower Drum Song,” would Hammerstein’s research about Judaism have been more serious?

It sort of surprises me that there isn’t more Jewishness in any of his major works. I sort of wonder why. I don’t think it was intentional or planned. I think he just didn’t find any story that appealed to him. I wish he had.

In 1952, Hammerstein wrote encouragingly to the author Felicia Lamport who had adapted her 1950 memoir “Mink on Weekdays (Ermine on Sunday)” about growing up in a wealthy New York Jewish family, yet in 1950, Hammerstein curtly rejected a proposal by actress Elna Laun to stage a Yiddish translation of “Oklahoma.” So Yiddishkeit was fine in its place, but not in his works?

In 1949, Rodgers and Hammerstein took an option on Irving Elman’s play “Tevye’s Daughters” based on the stories of Sholem Aleichem. What’s not clear was whether they wanted to musicalize it or produce it as something else. What put the kibosh on it was they contacted [director] Joshua Logan and he said he wasn’t interested and did not “care enough about Tevye’s fate.”

In 1931 Hammerstein proposed a radio program to NBC as a “musical dramatic-comedy” about residents in a Bronx apartment building, with a Jewish family living on the third floor and an Irish family across the airshaft. Was Hammerstein aiming at an “Abie’s Irish Rose” style of forced juxtaposition between Jewish and non-Jewish lifestyles as a surefire audience grabber, finding entertainment in New York melting pot confrontations?

I don’t think he was going for conflict as much as variety. In the melting pot, he was not looking for anything like the Irish against the Jews. He just liked the idea of having all these various types and ethnicities that would give many opportunities for working with different stories. It was a very clever idea.

Among celebrated Jewish refugee theater creators from Fascist Europe, Hammerstein almost worked with the composer Emmerich Kálmán, and did adapt Ferenc Molnár, whose play “Liliom” became “Carousel.” Given the glitzy, glamorous aura surrounding Kalman’s works such as “Countess Maritza,” would he have really been a suitable collaborator for Hammerstein, whose works were more like fanfares for the common man?

Oscar started by doing operettas and it was an evolution from “Show Boat” in 1927. Before that, the first show he produced was an adaptation of a German operetta in London where he redid the lyrics. Hammerstein worked with Sigmund Romberg on [the operetta]“Rose Marie.” Which makes “Show Boat” all the more remarkable. There really had been nothing like it.

In 1948 the songwriter Harry Ruby wrote to Hammerstein, mentioning he would be going to a Halloween costume party at Groucho Marx’s home. Ruby claimed: “I was going to go as a middle-aged Jew, but none of the costume companies has that kind of get-up.” Ruby added, “Halloween, while not as sacred as Yum Kipper (sic), is nevertheless a very important Jewish holiday. It commemorated the birthday of Meyer Halloween, who distinguished himself as a notary public during the Thirty Years War.” In 1959, Ruby wrote to Hammerstein again, trying to amuse him before cancer surgery by recommending Ben Hecht’s novel “A Jew in Love,” which Ruby summarizes as a “touching, tender and human story about a Jew who is in love. It came very near stopping all Jews from falling in love.” Clearly Hammerstein relished Jewish jokes and maybe found them a comfort at times?

Of all the regular correspondents with Oscar, the funniest in general by far is Harry Ruby. He just has a twinkle to him, like a daring little naughty boy and I think Oscar got a kick out of them. There were more Harry Ruby letters than I had room for. He is certainly the funniest of the correspondents and had a very Jewish persona.

In the early 1950s, Hammerstein wrote to the playwright George Axelrod, of Russian Jewish origin, producer Billy Rose and composer Harold Rome, soliciting donations to the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies of New York, praising their “wonderful work” in running hospitals and welfare agencies. Did he only target Jews with these appeals?

The reality is that most of Hammerstein’s friends were Jewish. The world he inhabited, the theater world, was largely Jewish so it doesn’t surprise me that these were the people he contacted.

Hammerstein’s memorial service in August 1960 at Ferncliff Cemetery, New York, featured plenty of Yiddishkeit, including a hymn, “A Noble Life, a Simple Faith” by Abram S. Isaacs, professor of Hebrew at NYU and editor of “The Jewish Messenger.” A reading from Isaiah 52:7 (“How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings, that publisheth peace.”) was followed by a text from the Christian Bible, Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians 13:1-13, about the importance of charity. And Hammerstein’s former doctor, Harold Hyman, who had apparently been the physician to Rodgers’ late colleague Lorenz Hart, read some poetry. Overall, a farewell with noteworthy Jewish elements?

Oscar also had a fairly Jewish sense of humor. There’s a certain sensibility about it that’s somewhat tongue in cheek, charming, self-effacing, a little naughty. I don’t think Cole Porter would do the same kind of humor and jokes that Oscar does. There’s a little gemütlichkeit there. More than anything, I got from Oscar how genuinely good he was. There is a certain deep morality about him that’s very touching. His passions were social issues, whether it be racial tolerance or pacifism.